Twenty years ago, Legally Blonde was released into the world and with it a thoughtful rumination on femininity that is still unrivalled in the mainstream. In Legally Blonde, femininity was not just a device to make women’s success and independence more palatable, it is precisely the reason its heroine, Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon), was able to succeed.

Despite its unrelenting heterosexuality, it’s this affirmation of femininity that earns the film a place in the femme media canon.

(And maybe it’s not that straight after all; a NewFest Pride online event on June 4 sees an all-LGBTQ2S+ cast doing a table reading of the script. Alexandra Grey plays Elle. And the movie’s famously campy “bend and snap” pick-up move has even been adopted by the likes of Love Connie, who made an appearance on Season 11 of RuPaul’s Drag Race.)

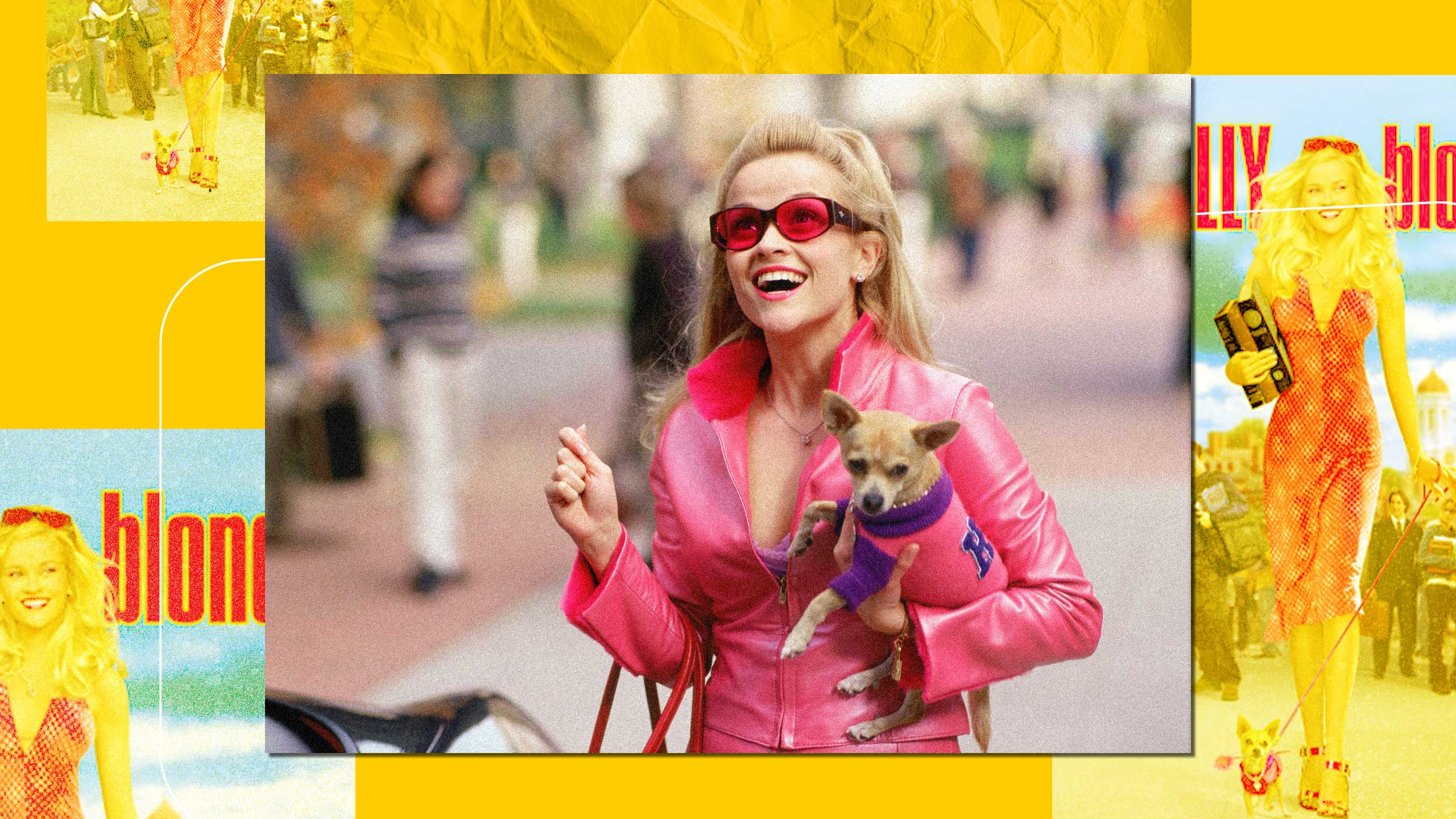

In Legally Blonde, we follow the blonde bombshell prototype Elle as she swaps the sorority house presidential suite for a Harvard Law School dorm room to prove she can be the “Jackie” (as in Kennedy, a.k.a. serious and brunette) and not the “Marilyn” (as in Monroe, a.k.a. sexy and blonde) that her recently-ex boyfriend claims he needs in order to become a United States Senator before he turns 30. Elle, the Gemini-vegetarian who hails from glossy Bel Air, is a fish out of water around her stodgy New England peers, and is ridiculed for her tiny chihuahua, pink outfits and bubbly demeanour. Of course, she ultimately triumphs, proving she has a sharp legal brain, winning the respect of her rival and realizing the guy she was chasing was a dud after all.

Legally Blonde emerged alongside pop culture productions like the Spice Girls, Sex and the City and Bridget Jones’s Diary as part of a wave of late 1990s and early-aughts “postfeminist” media. This era of pop culture gets called “postfeminist” because it presents a kind of airbrushed feminism: feel-good stories about women’s empowerment and success that take a pass on the burden of addressing systemic, intersectional oppression. For example, the Spice Girls’ shouts of “Girl power!” were certainly a vibe, but ultimately failed to articulate why girls ought to be empowered.

A return to a hyper-feminine aesthetic—an aesthetic previously deemed pro-patriarchy by many feminists through the 1970s and ’80s—was a huge part of the postfeminist cultural shift, as well as postfeminism’s re-imagining of feminist principles. It was in this era that we got more comfortable with the idea that looking and feeling sexy could be empowering rather than degrading, but “sexy” was still largely defined in normative or hetero-patariarchal terms—white, thin, blonde.

“‘Bridget Jones’ treated femininity as a comically unachievable pursuit, with unglamorous mishaps with off-brand Spanx and calorie-counting.”

According to feminist media scholar Rosalind Gill, academics became more likely to understand femininity in terms of the body, especially how it looks and how we maintain it, and less in traditional terms, like through domesticity and servility. So, the heroines of the postfeminist media era—like Elle Woods, Carrie Bradshaw and Bridget Jones—paid considerable attention to the body and its adornment. Femininity was essentially a commodity in SATC, where the main characters were presented unrealistically pursuing endless designer labels to signal their empowerment, independence and success. Bridget Jones was more relatable; the movie treated femininity as a comically unachievable pursuit through her unglamorous mishaps with off-brand Spanx and calorie-counting.

Femininity is framed as equally store-bought in Legally Blonde: Its opening sequence is a montage of Elle’s carefully-constructed feminine presentation, comprised of shots of nail polish, a pink razor, a truly staggering amount of exercise and a box of Herbal Essences blonde hair dye. But there is something different—and significant—about the way femininity is treated here. While similar montages appear in Bridget Jones, there is a sharp difference in how it plays. The time spent lingering on scenes of aesthetic labour in Legally Blonde have a reverent, almost ritualistic tone, while the aesthetic labours in Bridget Jones feel punishing, burdensome, certainly laborious and are played for comic effect. Legally Blonde didn’t make a joke out of femininity. Even when some of its characters try to make Elle look foolish in her femininity—her professors are bewildered by her pink and scented resumé, and one classmate approximates a Valley-girl accent to mock Elle—they were never successful. The film keeps audiences on Elle’s side.

Elle’s biggest antagonists are her ex-boyfriend Warner Huntington III (Matthew Davis) and his new brunette girlfriend, Vivian Kensington (Selma Blair). Vivian tricks Elle into showing up at a party in a Playboy bunny costume in an effort to humiliate her. But Elle gets the last laugh, dressing down Vivian’s “frigid bitch” costume before embracing her bunny look and going about her business.

At this same party, Warner offers her the horrifying compliment, “Don’t you look like a walking felony” and in the same breath tells her she is “just not smart enough” to succeed in law school. Anyone on the feminine gender spectrum knows all too well how femininity is undermined and devalued at every turn, seen as frivolous, weak and vapid. In the queer community we call this “femmephobia.” But femme researcher Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin says that femmes aren’t the only ones who face discrimination because of their femininity.

“I’m commonly asked who is impacted by femmephobia,” Hoskin told me in an email. “I feel like the real question is, ‘Who is not impacted by femmephobia?’”

“Femmephobia also shames boys and men for engaging in anything deemed feminine, from expressing emotion to moisturizing their skin.”

Hoskin defines femmephobia as the “systematic way that society upholds and regulates the norms of femininity while also devaluing all that is feminine.” This means “sissy,” which shames boys and men for engaging in anything deemed feminine, from expressing emotion to moisturizing their skin. With this broad definition, everyone including masculine-of-centre folks and straight women like Elle are impacted by femmephobia. After all, the discrimination that Elle experiences is based on her femininity, not just her gender.

“[In Legally Blonde] it isn’t necessarily women who are trivialized—though, there are scenes where Vivian and Elle encounter blatant sexism from Professor Callahan—but more accurately feminine women,” says Hoskin. “To me, that is femmephobia.”

Legally Blonde’s contention with femmephobia isn’t often noted, even by those who praise the film’s feminist spirit. Since its release, many writers have argued that Legally Blonde is more feminist than it initially appears. The sexism that Hoskin refers to drives a subplot about workplace sexual harassment almost 20 years before the #MeToo movement made it a mainstream conversation. In the movie, Professor Callahan (Victor Garber) comes on to Elle in his office, promising he can advance her career. Elle is left devastated and questioning her abilities, but her network of women friends and colleagues swoop in to lift her up and take Callahan down. Callahan is called a “scumbag” and fired by his client Brooke Taylor-Windham (Ali Larter). (She had hired him to defend her against the charges of killing her husband in the movie’s pivotal high-profile murder trial.) That leaves Elle in the perfect position to take Callahan’s place and win the case with her encyclopedic knowledge of perm maintenance. This treatment of sexual harassment and its possible consequences earned Legally Blonde the title of “a proto-#MeToo manifesto.”

“Early-aughts fictional and celebrity women like Elle, Britney Spears and Paris Hilton were sorted into categories of ‘good’ or ‘bad.’”

Writing for Bitch media, Erin Taylor, too, applauds the subtle way the film skewers the male gaze and the Madonna/Whore complex that sorted early-aughts fictional and celebrity women like Elle, Britney Spears and Paris Hilton into categories of “good” or “bad.” Taylor argued that it’s only now, 20 years later, that we have the language to locate this mistreatment in misogyny and whorephobia. Indeed, recent documentaries gave both Hilton and Spears a more compassionate and complex reading—and perhaps gave our culture a second chance to reconsider its misogynistic treatment of young women in the public eye.

Whorephobia, misogyny and femmephobia are all related, sharing in common their devaluation of women and certain kinds of femininity. So to see it challenged on the silver screen was impactful for femmes—even if Elle was straight.

In the absence of robust queer media representation in the early 2000s, we had indies like But I’m a Cheerleader and Kissing Jessica Stein, but not yet the mainstream femme representation of The L Word. Figures like Elle could become meaningful icons for femmes. I asked my online community of femmes how Legally Blonde affected them and many responded enthusiastically. Watching Elle be her bubbly and feminine self in a place like Harvard Law School continues to remind femmes that they belong in their school or profession, that they can do serious things and still be feminine, that femininity doesn’t foreclose the possibility of intelligence.

In fact, femininity can be its own form of intelligence. As much as Elle’s femininity makes her a target—one sales clerk took in the blonde hair and gaggle of gal pals and thought it was her chance to sell last year’s fashions at full price—it is also Elle’s femininity that protects her. As a fashion major, Elle knows that a “half loop top stitch on low-viscosity rayon” is impossible and also knows that the dress being pushed on her was on the cover of Vogue a year earlier. These quick calculations means she also knows that said salesperson is full of shit.

Elle’s femininity also proves to be her edge in the story’s climatic murder case: Her sorority-bred value of “sisterhood” is what gained the trust of her sorority sister Brooke Taylor-Windham, the woman accused of murder, and, importantly, helps Elle understand Brooke’s air-tight but supposedly shameful alibi—she was getting liposuction at the time of the murder. To avoid ruining Brooke’s fitness empire (and the bonds of sisterhood), Elle keeps the alibi secret, even though it might have easily won the case. Instead, it’s up to Elle’s trademark feminine knowledge to do the heavy lifting. In the end, it’s her intimate knowledge of the “cardinal rules of perm maintenance” that clinched the murder trial and burned the words “ammonium thioglycolate” permanently into my brain: knowing that perms are destroyed if wetted within 24 hours is the crucial bit of information that unravels the defence case and reveals Brooke’s stepdaughter to be the true killer. It’s this elevation of feminine knowledge—powerful enough to crack a murder case—that is the crux of Legally Blonde’s contribution and what, for me, earned its place in the canon of femme media texts.

The film’s thesis is, essentially, that there are more ways to be brilliant than we have perhaps been told. Legally Blonde zoomed in on the brilliance of femininity, assuring a generation of femmes that it isn’t something they need to suppress.

While the devaluation of femininity has been the topic of feminist and femme intellectual labour for decades, Elle Woods is still the pop cultural icon that makes complex conversations about misogyny and femmephobia legible to the mainstream, even 20 years after Legally Blonde’s release.

Writer Emmy Potter last year pointed out that Elle, if she were real, would have been at Harvard at the same time as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Considering what we know about the social network’s sexist origins, my latest femme-inist fantasy is thinking about the brilliant ways Elle would have taken him down, too.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra