In I Love Shopping (2019), Lauren Cook’s debut poetry collection, Cook pieces together anecdotes, stories, facts about orchids, texts from his mom and lines the length of a fortune cookie. In that collection, his voice is at times like a child gleefully reading out a Wikipedia entry to a friend; at other times it is all jokes, and then flips to a bug-eyed, hand-holding seriousness. Cook writes in I Love Shopping, “Doing things jokingly is a gateway drug to doing things sincerely.” In I Love Shopping, there’s a sense of yearning, a futurity at the heart of his writing. He says, “I am just 10 years old, so I’m trying not to pre-emptively start a mythology about myself, but I am magic … I want a fashion line and I want to save the elephants.”

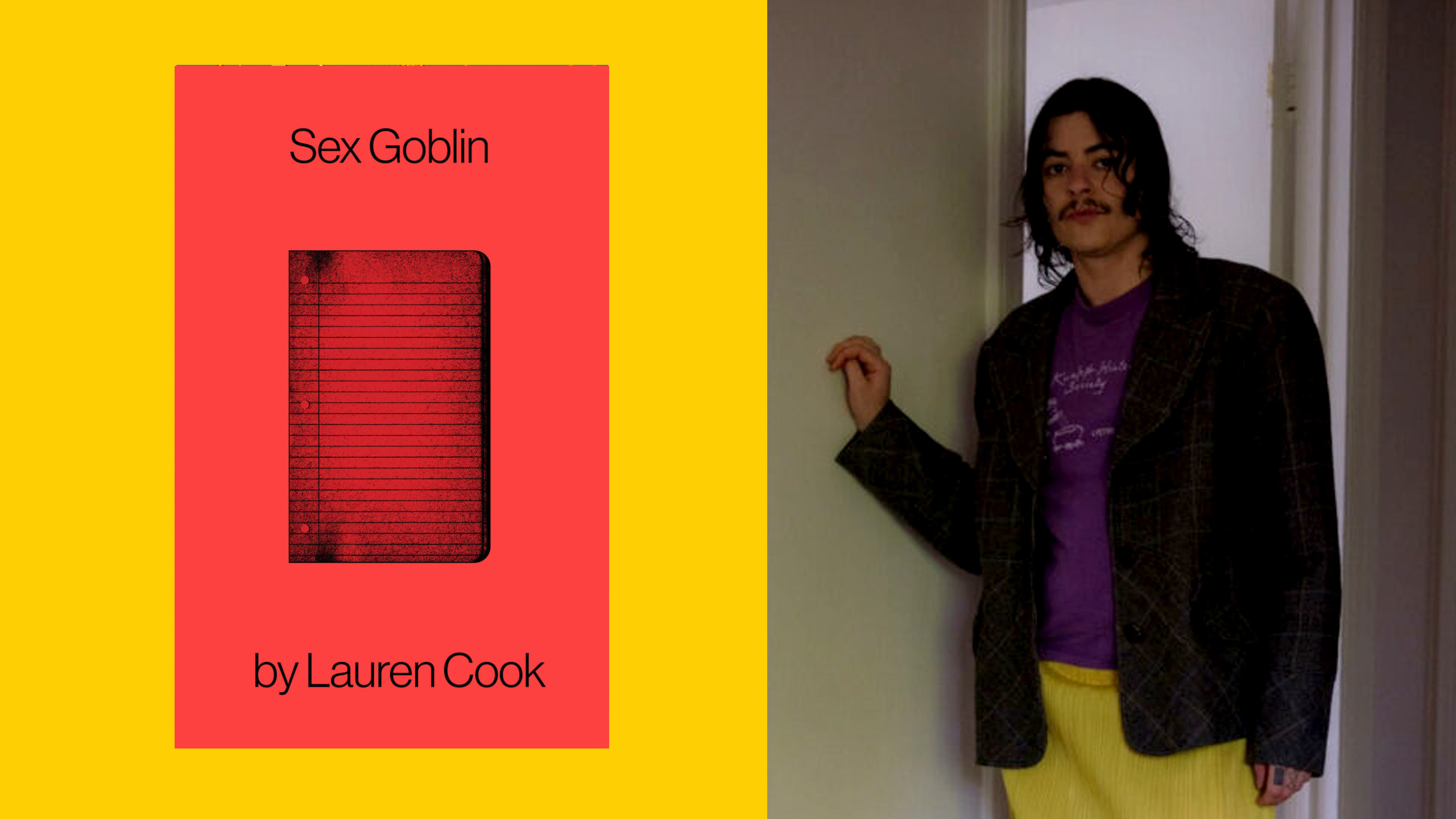

Cook has followed I Love Shopping with Sex Goblin, a prose collection of stories and fables. In Sex Goblin, Cook has allowed his stories more breathing room. It is a collection written with dumb candour about violence, sexuality and processing life. The stories are about gym crushes, a bathtub falling through the ceiling, hooking up with a lesbian softball catcher, four-leaf clovers and hazing rituals. As in I Love Shopping, there’s a childlike straightforwardness. Cook’s tone remains naive but thoughtful, both caring and stupid. The characters in Sex Goblin occupy a Tumblr-style register, mixing ha-ha irony with a profound sensitivity and warmth. He writes with a sense of wonder, introspection and sadness about nature, relationships and love. In an early passage in the book, he writes: “Sex goblin forgot that having fun means forgetting what things mean … Sex goblin can only listen to music with words in it.”

We spoke about Sex Goblin, language, fantasy and overprocessing.

Lots of the time your tone is deliberately stupid in a way that reminds me of a lobotomy-twink-speak or something like that. Why are you doing that in your writing?

To me, I think it’s more like a kid. And I guess a kid can be a twink, but more like a child. There’s something about processing something that’s happening in real life through the lens of this incredibly stupid child that I think lives in me and other places in people in a lot of different ways. Obviously too, it is inspired by the way people talk in internet comments or this sort of mass cultural communication. I just really like the idea of someone figuring something out in real-time and [being] really unashamed of expressing it too.

The child’s voice rings true the most in the “aw shucks”-ey way of writing that you have. And then there’s also this sort of slightly more self-aware register. Sometimes I thought the voice in Sex Goblin plays up its own dumbness.

This whole kind of thing is about this play between what’s true or false. Basically being like, “Oh, if I’m writing something, I’m an actor in writing it.” This adds something to the conversation about artifice. I think I just generally have this thing too, where I’m like, “Writing a story is lying.” And I think with this specific thing, with this childlike narrator, I’m like, “No, it’s lying.”

In both your poetry collection, I Love Shopping, and Sex Goblin, you spend a lot of time in the first person.

There’s something really interesting to me about telling a really benign story with a really intense personal voice and the really intense personal voice being the story. There are obviously stories [in Sex Goblin] that are based in reality or things that did happen, but the analysis and the telling of it is not how I would tell the story to someone. I think the whole book is about this really childlike, stupid character interpreting and witnessing sexuality and nature and violence—and through the stupidity essentially alchemizing it into something that doesn’t affect them in the way that things that happened to me affected me. So, if anything, it’s a fantasy about that. About being able to be so naive that you can [deal with] witnessing things that you don’t understand or things that scare you or things that are traumatic to you or violent and being able to be, like, “Hmmm, anyway …”

It’s the opposite, in a way, of schools of therapy like cognitive behavioural therapy, which ask you to use your thinking to work through a particular psychic or emotional problem. A narrator in Sex Goblin says, “My message to Carrie Bradshaw is your thoughts are your enemy.”

I transitioned a while ago, but I became a gay man later in that process. Becoming close to a lot of gay men and having them tell you a story from when they were young or whatever and being like, “That’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard.” And they’re like, “It wasn’t, though.” There’s something about that experience that just fascinated me. The way that you alchemize this terrible thing that happened to you to survive in a way different to how I did.

Lots of people, usually cis people, have asked me about my reasons for transitioning. I think there’s a particular trans experience or response which is like, “Babe, I don’t know. This is just what I’m doing and it feels really nice.” Which gives me a lot of sympathy for a non-reason-based way of living life.

Totally, and just being like, “I’m actually just not thinking about it. It’s just happening.” Every single person that I know for the most part who are trans don’t think about it that much, don’t talk about it that much. If it’s part of our lives, it’s not what we spend our whole time talking about. There’s a collective understanding of,“Why would we even talk about this when we’re together? Let’s have some peace.” And maybe that’s a part of it.

Your writing definitely has a trans inflection to it, but it’s not like, “Lauren Cook comma trans writer.”

Totally, I’m not like, “So, this is how it all began.” I’m not gonna shit on that. But I do have a really hard time interacting with any sort of trans narrative where it’s like: the beginning, middle and end of every single thing you want to say. The only time I do think about it is when something outside of me comes out of nowhere to be like, “Oh, by the way.” But otherwise the everyday experience of it, the trauma of it, the joys of it, I’m just like, “Eh, I’m chilling.”

Yeah, until you’re confronted with it. Some people can’t be just chilling in the same way.

Totally, and I think when I say a lot of trans people I know are just chilling, it’s like this fantasy of chilling. It’s a repression. Like, eating at a restaurant with someone and being like, “Every single person is staring at us. It’s not even a made-up thing. It’s not even a joke.” And to just be like, “We’re chilling.”

Your writing, by being in these fantasy- and fable-like forms, feels at odds with the realist trend in contemporary trans writing, Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby being the most prominent example of that. The narrator in Sex Goblin says, “I’m not looking for reality/ I’m looking for a simulation of reality.” What is it about the fantasy and the fable that you are drawn to in your writing?

I’m a big fan of stories and I feel comforted by stories, especially fables. They pose a very immediate question, muse on it a bit and then provide a little answer. I find that throughout life to be so satisfying.

I don’t know if the flip side too is that there’s really nothing that interesting about me. I’m just a guy. Not in a bad way—all people are special—but if I write a whole story about my life and take the word “trans” out, it would just be a story about some guy. Just some super regular white guy. And that’s not a terrible crime; there’s just no interesting story there to me. I don’t think this is true of everyone, but there is a view of selling your story that sometimes I agree with and sometimes disagree with. I don’t know if I want a bunch of cis people to read a book about how I transitioned and be like, “Oh, now I can draw conclusions from this.”

In the book, you write that a character “tells the world she is a top and is a top to the world. I’m not here to argue that, I just also know most people also want to be fucked every once in a while.” Are you saying that this top/bottom dichotomy is a silly part of our culture or a funny part of our culture, but not a genuine part of it?

There’s such a phenomenon of the commodification of those types of terms. Like straight people will literally be like, “I’m a top.” And I’m like, “That’s not possible. It’s just not possible for you to be a top. You’re the man in a heterosexual relationship. You’re just performing the age-old tradition of heterosexual missionary sex. Who even taught you that word?”

When people are like, “So-and-so is a twink.” And I’m like, “Bruh, you’re a 13-year-old girl from the middle of nowhere. You can’t just call Troye Sivan a twink in a derogatory way.” I understand it’s quite funny. It’s not a crime. But people did not used to know these words, and it’s definitely a double-edged sword in a lot of contexts.

People will be like “Timothée Chalamet is a gay bottom.” And I’ll be like, “That’s not a bad thing. “When you boil that down, they’re just being like, “He’s a fag.” Like, yeah, he’s kind of faggy, but you’re just calling someone a fag derogatorily, but in more taxonomically appropriate words. Like you’re just calling it its Latin name not its colloquial name.

In your writing, there’s so much romance and intimacy. Your characters have a profound sensitivity. One of the characters in Sex Goblin says, “Sometimes, someone touches your back and it feels like the hand of everyone you always wanted to touch your back.” Could you talk about how romance shapes your understanding of the world?

I think I just love love, maybe. Almost in a joking way, but I do love love. I think I just find it to be, like many who came before me, the most interesting thing that can happen both in a good way and a bad way. It’s something that has both marred my life and made it better, but I do think it’s one of the most interesting things that can happen. I definitely think, too, that it’s so little-kid, it’s so movie, it’s so TV show, it’s so pseudo-reality in a way that I just think thematically fits in with this collection.

You describe yourself as a naturalist. And in I Love Shopping, there’s lots of the natural stuff, but the settings in Sex Goblin, in general, they’re in urban banal semi-rural settings like gym sessions, regional grocery stores and cars—not bugs and fields. How did naturalism play into your life at the time of writing the book?

It always has with the way I was raised, and what I went to school for. And I do think there’s some sort of parallel between animals existing in these spaces, squished in between like birds migrating or raccoons eating trash or something navigating these spaces in between us that sort of mimics this understanding of sexuality or this survival in this other way that’s talked about in the book. But in general too, I did live in a city for a big chunk of writing it—in the Bay. There’s something about making the best of what you have that mimics the rat-in-the-trash-can type of thing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra