Maggie Dort (aka Land Shark) of the Death Track Dolls & Charlene Jobborn (aka Dickless Tracy) of the Smoke City Betties. Credit: Glenn Mackay

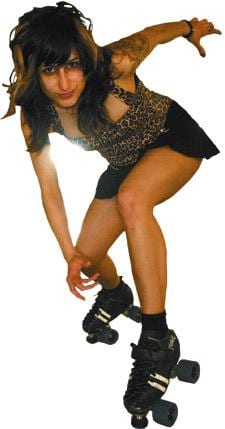

Natasha Jesenak (aka Nasher the Smasher) of Chicks Ahoy. Credit: Glenn Mackay

They’re here, they’re largely queer and they’re ready to kick ass on roller skates. The women of the Toronto Roller Derby League (ToRD), this year’s honoured group in the Toronto Dyke March, aren’t shy about combining sex and sport.

“We enjoy celebrating our sexuality here,” says Natasha Jesenak, aka Nasher the Smasher of the team Chicks Ahoy. “We can make that part of the game and make it part of the way we get along with each other.”

“I’m a big girl,” says Liz Vanderkleyn, aka The Hoff also of Chicks Ahoy, “but I feel hot when I’m out on the track because [derby players] come in every demographic.

“Out there I feel more me than anywhere else in my life.”

On game day inside the George Bell Arena — ToRD’s home rink this season — it quickly becomes clear that a big part of roller derby’s appeal is the celebration of an alternative aesthetic, one that leaves room for a wide range of ages and body types. Along with their requisite safety gear and roller skates everyone is decked out in fishnets, dramatic makeup and campy team costumes emblazoned with cheeky names like Dickless Tracy and Must Bang Sally. For many, tattoos, piercings and punk-rock hairstyles top off their fierce DIY look.

Vanderkleyn says Derby’s alternative bent makes for an easy connection between the sport and their involvement in Pride.

“[Derby]’s such a different thing to do and the [queer] community is kind of about being different from everyone else,” she says.

Like any sport roller derby has rules that govern the game play. The basics go like this: In ToRD roller derby is played on a flat elliptical track. Each game has two 30-minute periods during which there are a series of jams. A jam, which can last up to two minutes, is a period during which points can be scored.

During a jam each team has five players skating on the track — one pivot, three blockers and a jammer. The jammers try to get through the pack as fast as they can; whoever laps the pack first is declared lead jammer and can call off the jam anytime she likes up until the two-minute mark. Once a jammer has lapped the pack she gains a point every time she passes a blocker from the opposing team. If a jammer laps the opposing jammer, it’s called a grand slam and an extra point is awarded to her team.

As their name suggests blockers try to block the opposing jammer’s progress around the track. Pivots, described as the “brains” in the lineup, attempt to direct the blockers to best slow the opposing jammer. In between jams teams have 30 seconds to set up their lineup for the next jam.

If that sounds confusing, you’re in good company.

“I think people who come to games are still confused about what exactly roller derby is,” says Maggie Dort, aka Land Shark of the Death Track Dolls. “It’s actually incredibly hard to talk about and sum up.”

The league has had its fair share of bumps in its three years and two bouting seasons since it launched. There have been some brutal injuries, extensive lineup changes and the dissolution of two teams — the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad and the Bay Street Bruisers. But the players, who own and operate the league, say despite all the pain, drama and weekly arrays of cringe-inducing bruises that the advantages far outweigh any pitfalls.

“It’s the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,” says Dort.

“[I’ve met] a million amazing people that I’ll probably stay friends with for a really long time,” says Alicia Bernard, aka Bambi of the Gore-Gore Rollergirls.

Players say they love beating up all their best friends, having the fans cheer when they get a great hit and seeing fan-made posters with their names on them.

“You feel like a rock star,” Dort says. “One time a little girl asked me for my autograph and I was like, ‘Can I keep you?’”

Queer players say that roller derby is also a great place to meet women for those who aren’t into the club scene.

“It’s just alternative to anything out there,” says Vanderkleyn. “As a sport, as a form of entertainment — I mean you could go to the bar, or you could come to a derby bout.”

For Dort roller derby introduced her to a whole new social circle and gave her a sense of belonging. Before she joined the league Dort says she was struggling to find a place for herself in the queer scene as a bisexual.

“Lesbians think you are either afraid to be without a boyfriend or you’re a stupid straight girl who just likes to fool around,” says Dort. “Roller derby is somewhere I don’t find that at all…. [Roller derby] just opened up to a whole new world that wasn’t just snotty bar scene dykes that were always so mean to me.”

Derby has also provided a space for players to question their sexual orientation and come out.

“A lot of people started the season thinking they were straight and by the end of the season they had a girlfriend,” says Dort.

“I think it’s just so much easier to come out when there’s so many people already accepting of that,” says Bernard. “I think it’s just easier for people to accept that or try that, because it’s so easy — there’s so many hot people.”

The league’s packed schedule — one game every other Saturday plus two to three practices a week — certainly ensures lots of tight-knit interaction.

“There’s a really fine line between [when] you’re in the change room and you’re half-naked,” says Dort. “[Then] you’re hitting each other, so it’s physical, and then you’re getting drunk together and there’s a lot of love, so you’re always hugging each other.”

“And then somehow you find yourself making out with someone on your team,” Jesenak pipes in.

“And it’s not a big deal,” Bernard adds.

The flip side is that when things end badly it can lead to drama within the league. Between practices, fundraisers and committee meetings it’s nearly impossible to avoid potentially awkward interactions between exes.

“People date inter-league, inter-team and if it goes bad it makes things a little tough if you’re on the same team as them or mess up your team dynamic,” Bernard says.

After a couple years of working to get the league up and running, being chosen as honoured group at the Dyke March is a big boost for the league’s profile in the queer scene, says Aimee Haskell aka Aimee Zing of Chicks Ahoy.

“Now we can come and say, ‘Hi, we’re the queer skaters and we’ve been here all along, we just haven’t really had enough going on to have our voice heard,’” says Haskell, “but now we do.”

“I think it’s really great because there aren’t as many female-focused sports around in general, never mind queer sports,” says Jesenak. “So I think that’s pretty amazing to bring that to Pride.”

For Dort having ToRD honoured at Pride is important because, unlike many other queer organizations that focus on advocacy, ToRD is devoted to having fun.

“It’s a group of women who are able to have a cause that’s not so serious,” she says, “and I think it’s important to show another side of the queer community.”

In addition to leading the Dyke March on Sat, Jun 27 with honoured dyke singer/songwriter Faith Nolan (turn to page 20), ToRD will be celebrating with an all-queer derby bout on Jun 26 called the Clam Slam.

An official Toronto Pride Week event, the Clam Slam will see local team the Clam Diggers play against Vagine Regime Canada, a team consisting of queer players from Edmonton, Victoria, Kitchener/Waterloo and Montreal.

The Clam Diggers is a team made up of queer players from the regular season ToRD teams, and while the team’s creation is tied to the Clam Slam, Haskell says she hopes there will be opportunities for the team to play at other events in the future.

Like all of the games so far this season the Clam Slam will take place at George Bell Arena near Runnymede and St Clair Ave W. It’s a long haul from gay enclaves like the Church-Wellesley village and West Queen West, something the league is all too aware of.

“Even though it may not be a Pride event in the downtown Pride area, I think we’re going to get those fans to come out,” says Jenna Cloughley, aka Mia Culprit of the Gore-Gore Rollergirls. “We might not get those people who are visiting from other places who don’t know Toronto very well, but we might get the key community here that doesn’t normally come to games.”

The rink’s inaccessibility is part of what’s triggered the league’s upcoming move — as of July ToRD games will be held at Downsview Park. Not only is the rink more accessible — just a 10-minute bus ride from the subway — it’s also fully licensed and, unlike hockey rinks, available to ToRD year round.

Players hope the added publicity the league is getting this Pride will increase the number of queer fans during the regular season — and maybe even attract new players.

“For us to get more queer players out would be awesome,” says Rebel Rock-It of Chicks Ahoy. “I think doing something like the Clam Slam will open us up to this whole community that would really enjoy what we do and really respect our ideas of women.”

Jesenak says you don’t have to be a whiz on wheels to get involved.

“As opposed to ‘You’re cut from the team because you don’t know how to skate,’ here we’ll teach you how, we’ll lend you skates and we’ll spend the time with you,” says Jesenak. “There’s still a competitive element while allowing those [new] people to learn and grow the sport.”

That support and camaraderie is a huge part of what makes the league appealing to players and the confidence gained through the sport make a difference in players’ every day lives, says Vanderkleyn.

“When I got involved with the league I was so incredibly shy,” she says. “Now I come in here and I have this big, boisterous Hoff personality. It’s amazing to have a community where you can be everything that you are without holding anything back. This community really helps foster that.”

Vanderkleyn speculates that increased confidence is why many of the players, straight and gay, get tattoos and piercings after joining the league.

“As you start feeling more you and more in touch with who you are, the more willing you are to cover yourself in what represents you and express yourself in really positive and personal ways,” she says. “Whether or not people are going to look down on it or frown upon your own representation, you’re you.”

As for criticisms about the sport being antifeminist because of the titillating outfits and bold monikers, Dort says the naysayers have it all wrong. She says the league’s freedom to let players shape their own identities and the atmosphere of acceptance is what empowers all the players, gay and straight.

“I wear whatever outfit I want, I choose whatever name I want,” she says. “We’re the kind of women we want to be.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra