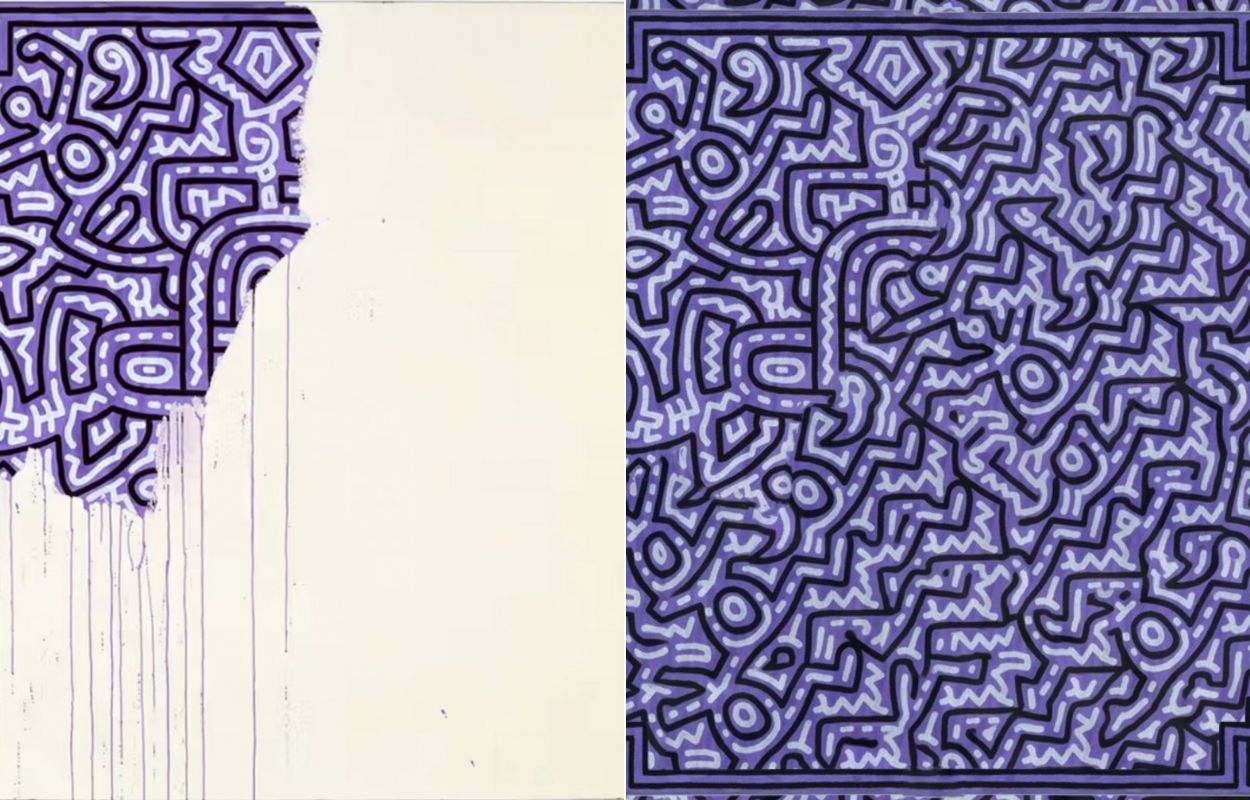

When an X user posted an altered image of Keith Haring’s famous Unfinished Painting last month, it caused a controversy. Despite the post’s tens of thousands of likes, the backlash of negative comments accounted for the incident’s ensuing media attention. Replies to the post referred to the altered image as disrespectful, abhorrent and even vile. The issue, multifaceted as it was, revolved around the fact that the post’s creator, a user who goes by Donnel, claimed to have “completed” Haring’s intentionally uncompleted work with the aid of AI generation. While the incident sheds light on a number of evolving ethical concerns surrounding AI-generated art, recurring claims that the original painting had been “ruined” seems to miss the one redeeming (and queer) takeaway that we might salvage from this bit of virality.

Haring’s original Unfinished Painting shows a series of the queer artist’s iconic figures in fluid yet sporadic movement. These figures and the vibrant background beneath them, however, cover only the upper left-hand corner of the canvas. The rest has been left blank, save for a handful of drips that cross over from above. Painted in 1989, just a year before Haring’s death, the canvas’s empty space, according to curator William Poundstone, was intended as “a surrogate for the artist’s AIDS-shortened career.” As many critics of Donnel’s post have suggested, finishing the piece with generative AI certainly works against the original painting’s message.

Defenders of the post are quick to point out Haring’s frequent mantra—that art is for everybody. Haring went to great lengths to make his work more accessible. He was known for his subway drawings, works hurriedly executed on the black paper panels that were used as placeholders for advertisements. In the 1980s, he was arrested a number of times for these creative acts, which were legally regarded as vandalism. Yet, at the same time that Haring was sneaking through the New York subway system, his work was appearing in solo gallery exhibitions where he was effectively able to break down distinctions between what was thought of as high and low art. Haring, too, was known for giving away posters he’d made for free. Commenting on these habits and his style more broadly, he spoke of his work as being “definitely art for the age of mechanical reproduction.” Those who see nothing wrong with the AI-completed version of Unfinished Painting are likely to have some of Haring’s own generous spirit in mind, but they might be forgetting that intensely political side of his art as well.

Granted, our cultural history has been a history of remixing—building on earlier ideas, images and messages by copying, transforming and combining them in new ways. Accordingly, we might consider what the remixed message becomes in the AI version of Haring’s work. Donnel offered his own take in a recent YouTube video, in which he responds to the negative attention he’d received.

“I can’t even remember if I even knew what the meaning or the intent behind the original was, and even if I had, I would have done it anyways,” Donnel recalled. “I just thought it was sort of funny.” One of the joys of art is that it is polyvalent. It can take on a wide range of meanings—from political protest to satire to humour. Still, the explanation offered here doesn’t even attempt to respond to what Haring’s work might mean to others or how the AI artist’s joke might come across poorly to those who do grasp the original painting’s meaning.

A number of critics have accused Donnel of posting the “completed” artwork merely as bait, a means of intentionally fishing for negative responses with the ultimate goal being greater engagement and attention. In the YouTube video, Donnel rejected this idea. Claiming that his post was intended merely as a joke, he also observed that it went too far. When a reporter from NBC News allegedly reached out to interview him, for instance, he considered the offer before doing a quick search of the journalist’s social media. Finding that she had liked a comment that referred to him as a “vile person,” he nevertheless accepted the interview request. In responding to the journalist’s questions, however, he said he turned to AI again, generating responses using ChatGPT. The AI-aided interview was not ultimately included in the journalist’s piece.

Beyond revealing this one particular individual’s enthusiastic views on AI art, the incident has also stirred up a number of broader and ongoing ethical questions surrounding generative tools like DALL-E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. Since these platforms first launched in the summer and fall of 2022, many artists have been understandably frustrated by—or at least wary of—the new AI wave. Shouldn’t artists whose works become training data for these programs be compensated in some way? Are artists able to opt out? Better yet, shouldn’t the default require artists to opt in? These questions have multiplied in the past two years, yet they continue to go unanswered.

As the discussions resulting from the completed version of Haring’s Unfinished Painting continue to shed light on concerns pertaining to the ethics and responsibility of generative AI tools, they also point to noticeable differences between the way we engage with art on- and offline. In claims from many of those outraged by this incident, the idea that Haring’s piece had been “ruined” came up time and time again. Perhaps obvious, but nevertheless worth noting, is that Haring’s actual work hasn’t been tampered with at all. Far from being ruined—in the sense of being permanently spoiled—the original painting continues to circulate around the world in the Art Is for Everybody exhibition, which is currently being shown at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Unlike the Monkey Jesus incident, which really did ruin—or at least forever alter (beauty, after all, is in the eye of the beholder)—a famous work of art, Haring’s Unfinished Painting is still intact. Now, there’s simply a new jpeg out there of a poorly completed AI version of the image as well.

In this way, the internet continues to offer us a flickering reality—a painting (or, at least, a painting’s message) can be simultaneously ruined and entirely untouched. The internet’s tendency to offer us these flickering realities in which seemingly contradictory states of being can both be true was observed back in 1999 by the theorist N. Katherine Hayles in her work How We Became Posthuman. Since then, however, it’s become a particularly useful means of describing how queer folks so often navigate digital spaces. Writing about this queer dynamic of the internet, another theorist, Lisa Henderson, observes, “Queerness had long ago taught me to recognize the experience of being at once in and out of place.” Not only is this flickering an experience, however, it’s also a strategy, a means of quickly taking stock of a situation and being able to reconfigure. Being able to flicker online, appearing and disappearing as needed, to leave one forum to regroup elsewhere, can be a useful means for all marginalized folks to make their way through what is, often, a hostile digital landscape—as some of the more heated replies to the original X post illustrate.

This paradox, too, reminds us of those contradictory ideas that Haring so often brought together in his work and his life. Art belonged in the subways and in high-end galleries. Art should be simple, and art should be nuanced. Art could be accessible, and yet contain a multiplicity of meanings. Haring longed to see what works he might create when he was 50, and yet accepted that such a reality “hardly seems possible.”

Most notably, perhaps, is his observation that “the best reason to paint is that there is no reason to paint … Nothing is important … so everything is important.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra