Kate Dolan knew she was queer at the age of seven but didn’t fully accept who she was or allow herself to act on it for another decade. These early struggles inform the work of the North Dublin native, who grew up to make coming-of-age films that reflect her Irishness and queerness—films that were non-existent in her formative years.

Since graduating from Ireland’s National Film School in 2012, Dolan has produced an impressive roster of shorts, commercials and music videos peopled with strong, independent and resourceful women. The moody horror film You Are Not My Mother, which had its world premiere this week at the Toronto International Film Festival, is her debut feature.

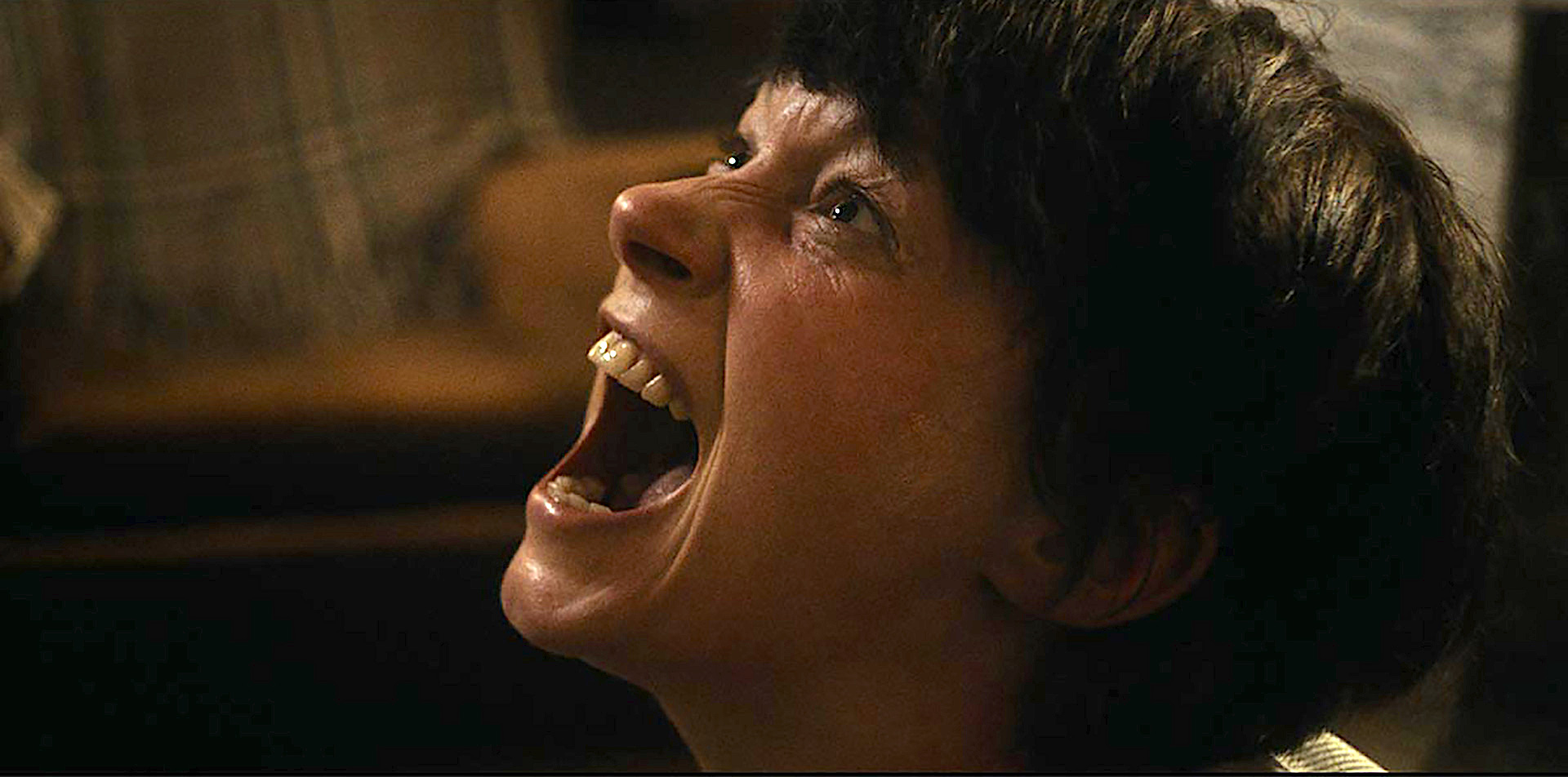

Set in present-day Dublin in the lead-up to Halloween, You Are Not My Mother follows Char (Hazel Doupe), a teenage girl who must deal with the aftermath of her mother Angela (Carolyn Bracken) briefly disappearing during a mental health crisis. With the help of her grandmother Rita (Ingrid Craigie) and her uncle Aaron (Paul Reid), Char struggles to accept that the woman who has returned may not be her mother, all while coming to grips with a secret that haunts three generations of her family.

You Are Not My Mother is not explicitly queer, but the story is told from a queer perspective: Dolan questions the fragility of biological families when blood ties are not enough and people are not who they appear to be. The North Dublin setting also echoes the experience of many queers; its working-class families living in council housing are economically and socially marginalized, the threat of violence is always around the corner and authorities aren’t always responsive to their concerns.

“She thinks she’s a witch. She was saying she’s gonna put a widow’s curse on anyone who wronged us when we were growing up.”

The film is also unabashedly Irish and steeped in pre-Christian pagan mythology. Dolan updates folktales about changelings (babies swapped at birth by faeries) for city dwellers and tackles mental health and generational trauma through the prism of horror. Her story is inspired by the dark tales the filmmaker heard growing up, and by the women who raised her, including her single mother, two grandmothers and an eccentric aunt.

“You’re kind of given these dark stories from a young age,” Dolan tells Xtra over Zoom from Dublin, “and even some of the myths and legends are slightly sanitized.” She describes the film’s grandmother as an amalgam of both of her grandmothers, but adds that her Granny Rose, who is especially superstitious, is a palpable influence in the film: “She thinks she’s a witch. She was saying she’s gonna put a widow’s curse on anyone who wronged us when we were growing up,” Dolan says with affection.

Despite the darkness of some of the film’s characters, Dolan wanted to celebrate the women in her life. Growing up, she found powerful female role models in the horror genre and she contrasts these films to drama or action movies that have “a male hero, who’s, like, doing all this amazing stuff, and then his wife just kind of goes, ‘Aren’t you amazing?’” She describes women in horror movies as strong, complex, nuanced and anything but passive, “kicking ass” and not letting “these big men overpower or scare them.”

Despite the autobiographical elements, Dolan was conscious that she wasn’t making a family history and wanted to let the film’s characters be their own family with their own story. “The ending is about making difficult decisions,” she says of Char’s journey. “You have to help your family, be there for your family and be a strong person in your family, even if those decisions are hard to make, and they require a lot of strength.”

“Do you give up? Or do you keep on fighting?”

“Do you succumb to the darkness?” Dolan wonders aloud during our interview, referring to the monster in the film and the real-world monster of mental illness. “Do you give up? Or do you keep on fighting?”

These questions fuel the slow-burn narrative of You Are Not My Mother. Char must find the strength to redeem her increasingly unhinged mother and bring her family back from the brink with the limited tools and experience of a working-class teenager. She also finds the courage to admit her family troubles to classmate Suzanne (Jordanne Jones)—a bully turned ally. In a touching scene, the teens acknowledge their respective parents’ mental health issues and bond despite their differences.

Bullying is a recurring theme in Dolan’s films, and looms large in You Are Not My Mother. Although she wasn’t targeted growing up, the director was conscious of the violence around her. “There were definitely people out in the community who were frightening,” she remembers. “There were people who would be walking home from the cinema and would get stabbed.”

Recalling her years at an all-girls Catholic school, Dolan sees schoolyard bullying as more insidious than street violence; unsaid words can hurt as much as taunts: “The silence says a lot more sometimes than them calling you a dyke to your face, which you definitely pick up on when you’re somebody who’s trying to figure themselves out.”

The schoolyard silence is deafening in Dolan’s first post-film school short, Little Doll. It tells the story of Elenore and Alex, two preteens who meet at a toy store and explore their budding same-sex attraction during a sleepover with other girls from their school. At the conclusion of this tender evocation of emerging queerness and a first lesbian crush, Alex is whisked away to hang with the girls of the in-crowd while a silent, dejected Elenore stands alone.

“Dolan recognizes that the Church has a devastating impact on young queers, but also says the Irish are far more tolerant than they may appear to outsiders.”

The sweetness and innocence of Little Dolls are echoed in Dolan’s 2018 music video for Pillow Queens’ “Gay Girls,” a playful romp featuring four rebellious girls in white communion dresses spending their first communion money on candy, pop, chips and gambling. Dolan recognizes that the Church has a devastating impact on young queers, but also says the Irish are far more tolerant than they may appear to outsiders.

“Catholic Ireland is quite a conservative place to grow up in.… It almost makes you not want to accept yourself,” she says. “But I feel in Ireland, one thing we have is great communities. I think the people of Ireland are very accepting and tolerant and kind. It’s more about the Catholic Church making you think that you shouldn’t accept yourself than a negative community [turning] against you.”

Little Doll and the video for “Gay Girls” were born out of a desire to depict “growing up quite young and knowing you’re queer.” Dolan says she did a lot of things that screamed “little queer,” and her mom’s reaction was, “She’s a tomboy.” She wanted to share these experiences on screen because depictions of early queerness are rarely shown on film.

A similar desire informed You Are Not My Mother. “I can’t really think of many coming-of-age films set in Ireland,” says the director. “[There’s] so much room for stories that haven’t really been seen.”

“There are a lot of big scary problems in the world, it’s hard to narrow it down.”

Dolan is already working on her second feature, another horror. Silent Caller is set in the same universe as her award-winning short, “Catcalls,” but is not a direct sequel. That earlier film paid homage to Cat People (both the 1942 original and the campy 1982 remake with David Bowie and Catherine Deneuve) and tackled the real-world problem of street harassment; Silent Caller, meanwhile, is about coming to terms with one’s sexuality as a teenager. It’s another coming-of-age story, but “through a different lens.”

Dolan says her next project is something she’s wanted to make for a while. “It’s important to me the films will be fun and entertaining, as well as kind of dipping into something that means a little more.” She expects to spend the foreseeable future working in horror and exploring what frightens her. “There are a lot of big scary problems in the world, it’s hard to narrow it down.”

There’s a lot to recommend in her current film. With bravura performances from its female leads and a storyline that mixes psychological horror, folklore and a scary monster, You Are Not My Mother evokes madness, family trauma and teenage angst as a young woman ponders the unthinkable.

You Are Not My Mother streams this week at the Toronto International Film Festival; streaming access may be limited to certain countries and regions.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra