I devoured this book. I hoovered it; I let its sorrow, its wonder, its yearning, swirl in the vacuum bag of my chest cavity. On every page there is so much honesty, insight, so much complex understanding.

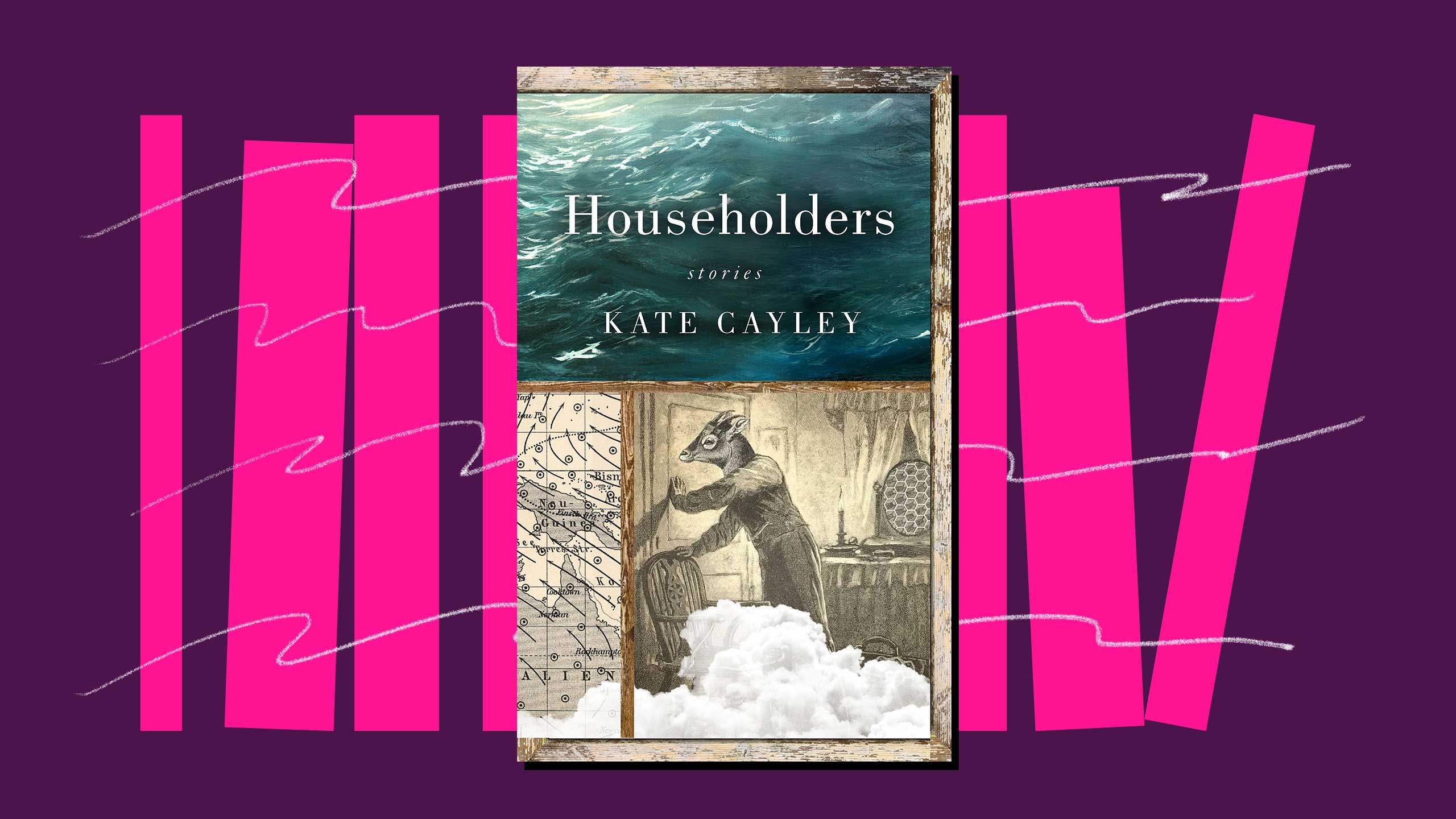

Toronto playwright and poet Kate Cayley’s first story collection, How You Were Born, won the Trillium Award and was short- and long-listed for the Governor-General’s Award and the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award.

If there’s any justice, Householders, her second collection, will grab all these awards and more.

The book has a telescopic view of time: The first story is set recognizably in our own time, while the second scopes back to the 1970s and plants seeds that will shoot up into other, connected stories, that bring us back towards and into the present and onwards into the future.

We start with Martha, a young worried mom in an immigrant neighbourhood in transition. She’s out of step with the educated, older, bourgeois moms in the neighbourhood as they plan a street party on the same day as the wedding of an old-timer’s granddaughter. Her son, fragile and volatile, is out of step with other children. These two tensions pulse through Martha, the one small and actable-on, the other huge, lifelong and much more difficult. There are no solutions, only turns and compromises and shocks that make perfect sense. It’s an expertly crafted story that feels effortless.

In “The Other Kingdom,” which I think of as the origin story in this linked collection, university students Carol, the high-achieving daughter of working-class Catholic parents, and Nancy, low-achieving child of academics, hit the road to “see America.” It’s the ’70s. Nancy is searching for something transcendent, she doesn’t know what. Carol’s stated purpose is to document protests against the Vietnam War. But really, she wants Nancy.

When they’re approached in Maine by an acolyte of a charismatic commune leader, they go see the guy speak in an abandoned house. And that’s it. Nancy is gone. Gone to the Other Kingdom, as the commune is known. She’s not even Nancy anymore, but Naomi. Carol has to drive home alone, with an inadequate letter for Nancy’s parents.

At the commune, Nancy/Naomi quickly becomes pregnant, and has a daughter, Trout, whose life we drop in on from time to time. She visits fellow commune-child (now artist), Strawberry, in Berlin, where Strawberry undoes Trout with a series of paintings of their childhood. Lest you think their ’70s commune names caricaturize or diminish them in any way, they are as fully realized as anyone in this collection. Here is Trout’s thinking just as Strawberry has complained about Berlin’s gentrification (“So clean, so nice-nice. I think it’s a plot to make all the cities in the world look like the same city”):

Trout, her spirits rising at the unfamiliarity of the street and the people, couldn’t see how this city was like any other city. She thought it was more difficult than that, to bleach out the particularity of a place, even if Strawberry had a right to her prissy nostalgia for what must have felt like her best times, when she was a precarious and avaricious young woman, sprawled in the mess of the former East, her eyes widening yes at anything on offer: art, sex, needles, history lessons. The world so much larger than she’d thought.

Other stories are more tangentially related to the Other Kingdom. In “A Handful of Dust,” a strange, out-of-time, maybe commune-raised almost-friend from university haunts the memory of a now-settled lesbian mom.

In “Pilgrims,” another child of the commune has taken off, leaving his girlfriend to care for his quadriplegic son. She finds herself starting a blog as Sister Bernadette, a nun caring for her disabled brother and yearning for the Camino.

Credit: Carmen Farrell

The stories glow with Cayley’s tenderness, her respect for all her characters (except maybe the self-serving wealthy who dance here and there in the background). Nancy is never mocked for wanting what she wants, for recognizing a lack in the “messy confidence” of her parents’ house, for noticing later a too-constructed note in Carol’s carefully curated ’80s feminist academic persona, her home and lesbian partner and dinner party guests, her speeches and pronouncements.

The commune, though it clearly damages its people irreparably, is not roundly condemned, nor is it celebrated. It just is, representing, maybe, so many human yearnings—for certainty of one’s place, for everyday spiritual life, for communalism itself, for giving over oneself to something greater than self.

Many of the non-religious characters in the book look at the religious ones with curiosity and envy. And yet, the reader can’t sit easily either with the idea that religious devotion, religious abnegation, is fine or isn’t scary.

The plague that drives a wealthy businessman, his wife, her sister and their support staff into their fabulously appointed bunker with young Liza, who doesn’t know why she’s there if it’s not to have sex with Neal, looks exactly like a plague of religiosity.

Pre-bunker, Liza and her lover Erin watch from their apartment as crowds of the infected walk by slowly—and, Liza notes, peacefully—below them. Liza asks Erin what she would do if she felt the silver rash on her neck that is the first symptom.

“I’d jump out the window,” Erin said. “I’d ask you to drown me in the bathtub.”

“Why?” asks Liza.

“Too much like church. Look at them, look at their faces. They all look so sure. I’d just rather be dead.”

Householders is both a straightforward and an ironic title. Nobody in this book is a comfortable householder. Home—decrepit bramble-enclosed trailer, Texas bungalow with mildewed bathtub, freezing rural communal farmhouse, gentrifying urban neighbourhood, luxuriously-appointed bunker—is a persistent question. What makes a home? How do we make a home?

People are only part of the answer. There’s attention to class and material difficulty. Conflicting ideas about how to make community. Do you will it into being? Buy it? Drum it up online? Perform it via street festivals with bubble machines and craft tables? What’s good for a community? What do we owe the people in our community?

Queers are woven through the book with great frequency and little attention to queerness. It just is, it’s just there, like the commune, part of life.

That the commune in the past is a draughty farmhouse where the hungry folk hunker down together for warmth, making small trades for food, and the commune of the future is a cushy bunker below ground, equipped with a hundred years worth of food, awash in large-scale immersive virtual experiences of the outdoors, of living consciousnesses without bodies, suggests that Cayley is in favour of a middle ground.

This book is not in the least didactic, which is part of what makes it good. The other part of what makes it good is that it has something to say, that it makes an argument. Pinning down exactly what that argument is, however, is tricky, and that, too, makes it good. But I think at least one thing is simply that community matters, that communality matters even if it doesn’t take the form of communal living. We cannot be householders only.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra