For over a century, society has struggled to understand who, why, what and how bisexual and pansexual people are what they are. We’ve tried Venn diagrams, adopted animal mascots, developed TV tropes and launched awareness campaigns. But even now, more than a century after the terms “bisexual” and “pansexual” were coined, people are still confused.

Through my years running the Bi Pan Library, a U.S.-based private queer literature archive, I’ve read stacks of nonfiction about fluid sexuality from the past century, and it’s no wonder we can’t get out of this cycle of confusion. If you’re looking for dusty old books by psychiatrists who believed bisexual people are not quite right in the head, you’ll be spoiled for choice. But if you’re looking for something positive, a Bisexual 101 perhaps, your options are limited to just a handful of titles that are still in print. There is certainly supportive, world-shifting bisexual and pansexual writing available if you know where to look, but it has not landed on the shelf without a fight.

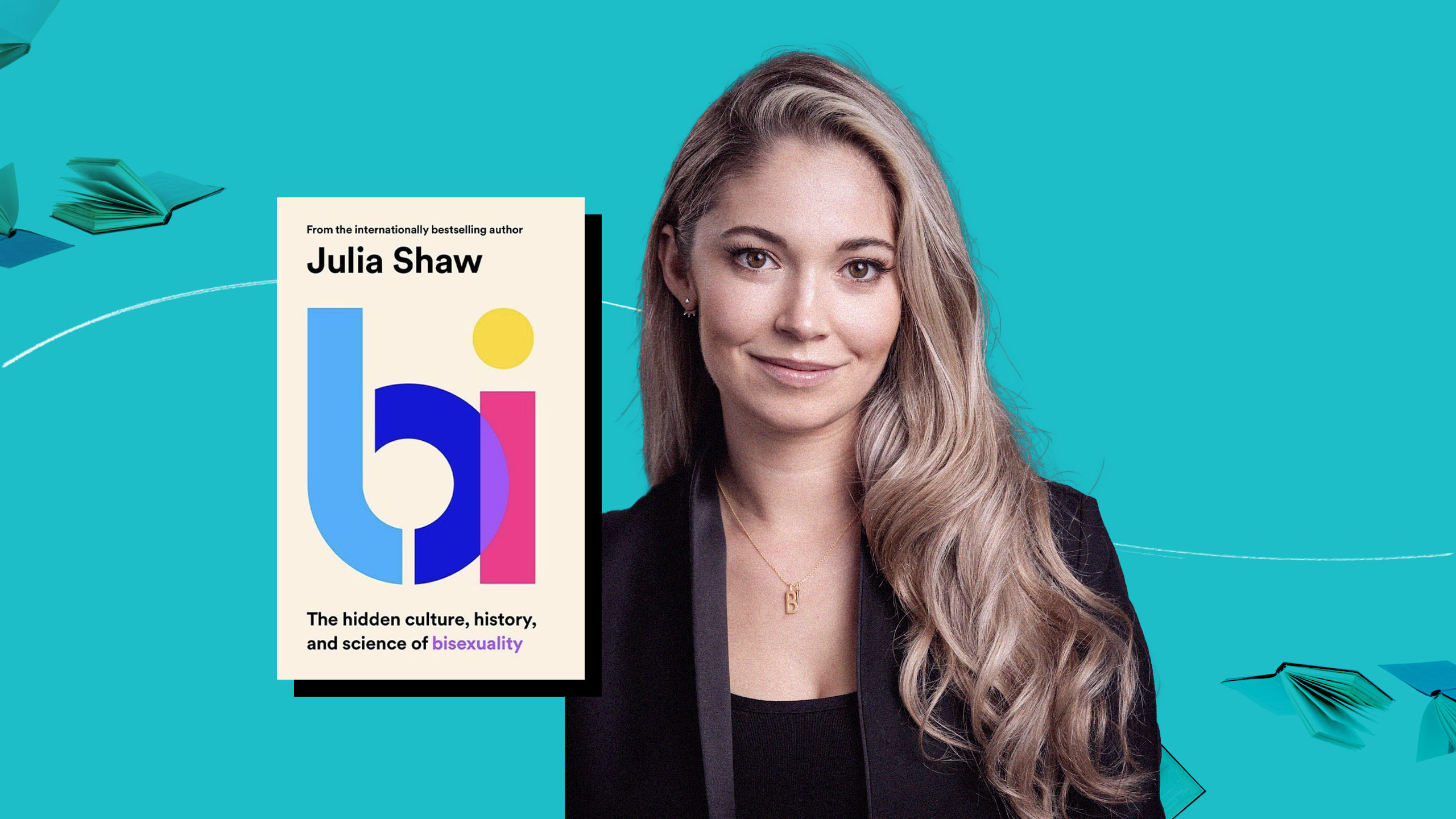

In the introduction to her hotly anticipated upcoming book, Bi: The Hidden Culture, History, and Science of Bisexuality, Dr. Julia Shaw shares the story of a publisher rejecting the pitch for her book because “we’ve already had that conversation,” despite that same publishing house never having signed a single book about bisexuality, much less anything like Shaw’s unique spin. While Bi does touch on all three things the title suggests—culture, history and science—at its core what Shaw has created is a whirlwind tour of bisexual research, from Alfred Kinsey’s notorious scale, to the life-or-death legal struggles of queer asylum seekers today. (Disclosure: Shaw has made donations toward the resources of Bi Pan Library, which I founded.)

That publisher isn’t completely wrong: we’ve certainly had conversations about bisexual identity. But who was speaking during those conversations? And were they enough?

Attraction beyond gender is not new, but the first books to focus on the subject didn’t come around until the 1920s, when psychological texts first cast plural attraction as deviant behaviour in need of curing. In Bi, Shaw (whose previous works include 2019’s Evil: The Science Behind Humanity’s Dark Side and 2017’s The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting and the Science of False Memory), profiles several psychologists and researchers involved in the early evolution of science’s narrative about bisexuality, a problematic cast entirely made up of white men. Physician Havelock Ellis, author of Sexual Inversion, enjoyed an open marriage with his queer wife—and was also an outspoken eugenicist. Sexologist Alfred Kinsey’s work forever changed how the Western world perceives sexuality, but his methods may have blurred ethical lines. Beyond-famous neurologist Sigmund Freud believed children start out with a hazy mingled sexuality—until they grow out of it (and let’s be clear, there’s a long list of other Freudian trash to take out).

These white-and-Western ideas trickled down to the English-speaking public through news coverage, and very quickly into pornography (of course). Erotic bisexual novels from the 1960s and ’70s were often thinly veiled as nonfiction case studies of “depraved” sexual fluidity. The back cover of 1966 pulp release Confessions of a Married Man claimed “the secret world of the bisexual has never before been revealed with such stark detail—its deceptions and duplicities, its anguish and its furtive pleasures.” The graphically sexual text presents a “true story” complete with an introduction written by a psychoanalyst. But if you flip to the title page you’ll find a bolded-caps disclaimer: “All of the characters in this book are fictitious …”

You can draw a clear line between these early salacious visions of plural attraction in literature and the ugly stereotypes Shaw explores in later chapters of Bi: bisexual people are “slutty,” homewreckers and dangerous, but somehow, at the same time, we don’t exist at all. Although English-speaking bi and pan people in the ’60s were already beginning to gather through the sexual liberation movement and queer organizing, our own perspectives weren’t broadly published or accepted. The story of who we were was still being written by others.

“If you’ve ever googled ‘am I bisexual?’ you may have come across the Klein Grid.”

Glimmers of hope appeared in the ’70s, with books such as Janet Bode’s View from Another Closet, which allowed queer women to describe their experiences using whatever words they felt comfortable with (including words many people mistakenly think are internet-age inventions, like pansexual and omnisexual). In Bi, Shaw profiles sex researcher Fritz Klein, a bisexual man who in 1978 released his iconic book The Bisexual Option: A Concept of One Hundred Percent Intimacy. If you’ve ever googled “am I bisexual?” you may have come across the Klein Grid, which he presented in The Bisexual Option as a more three-dimensional response to Kinsey’s one-to-six scale. By bringing his personal experiences into his work (much like Shaw has) Klein called for a new generation of scientific research that he hoped would investigate the true challenges and needs of his community without treating us as diseased, or focusing entirely on our sex lives.

But speaking of disease—the world’s growing curiosity turned poisonous in the 1980s as HIV/AIDS sunk its teeth in. As Shaw put it, “bi men were seen as a threatening connection between the dirty and the clean … a threat to heterosexuals everywhere.” The literature was nasty. Authors like Ivan Hill profiled bisexual people with straight partners, whipping up fear of inevitable illicit affairs or “unhealthy” open relationships. Hill frames his interviews in The Bisexual Spouse with a nationwide survey measuring psychiatrists’ opinions on sexual orientation; the study asked questions like “can homosexuality be modified toward heterosexuality, and if so, what therapy do you most often prescribe?” It’s nauseating stuff, but when I read my own yellowing copy of The Bisexual Spouse, I was struck by how sadly relatable the stories of his interviewees felt. These were queer people born between the 1920s and 1940s who didn’t have words for themselves, who were afraid they wouldn’t be believed, who faced prejudice in straight and gay communities alike, who felt there were very few resources to help them build a happy, balanced life.

It was amidst the fear and judgment of the ’80s that bisexual and pansexual people fighting for control over our own narrative developed a new strategy. The Off Pink Collective in the U.K. independently published Bisexual Lives, a slim book of essays and personal accounts written by and for bisexual people. As far as I know, Bisexual Lives marked the first time a group of bisexual people were able to tell their own stories in a book without being filtered through the lens of psychiatric analysis or pop-nonfiction appeal. Personal essay collections have since become a grand bisexual tradition in resistance to the idea that there is only one way to be bisexual, or even a single definition or word we all agree on. Instead, these writers described bisexuality as our stories, together.

“I was already so used to being sexualized as a young woman that I was worried that the label bisexual would lead to me being hypersexualized and that no one would take me seriously.”

Shaw follows this tradition in Bi, illustrating cold, hard, queer statistics with her personal stories of realization, heartbreak and joy. In Chapter five, titled “Invisi-bi-lity,” she describes how she was worried that looking bi would be problematic for her career as an academic. “I was already so used to being sexualized as a young woman that I was worried that the label bisexual would lead to me being hypersexualized and that no one would take me seriously.” She contextualizes this raw vulnerability with sexuality researcher Julie Hartman’s study of what—if anything—it means to “look bi,” and how bisexual people often combat their invisibility with clothing, hairstyles and body language.

As bisexuals were increasingly acknowledged in broader queer activism and pop culture in the 1990s, more critical books also sprung up to address the unease many people felt toward “strict” labels. Feminist psychologist Lisa M. Diamond argued in Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire that sexuality could not be measured or described without acknowledging how self-perception can change across a lifetime, praising Klein’s incorporation of past, present and future self-concept in the development of the Klein grid, even though according to Diamond, it “did not take hold.”

Speaking of Klein, our researcher friend kept himself extraordinarily busy in the ’90s. He released two more books, founded the American Institute of Bisexuality and in the early 2000s headed up the Journal of Bisexuality, the first academic journal to specialize in bisexual and fluid issues. Many of the queer researchers Shaw references in Bi first presented their work in the Journal of Bisexuality, climbing through the window Klein had propped open for them. At last, scientific research and literature about bisexuality was being wrestled into our custody.

Research and academic writing about plural attraction has become increasingly queer-led and destigmatized ever since. Because of this, we’ve begun to better understand the specific challenges our community experiences. Shaw explores much of this new ground in Bi, walking through very recent research into the harrassment bisexual people face in the workplace, our disturbingly high rates of mental illness and intimate partner violence and how sexually fluid asylum seekers slip through inhumane cracks in the legal system. Thanks to queer researchers, being studied may finally begin to work toward our benefit.

“The diversity of language blossomed with the ability to connect with like-minded people and to learn about a universe of queer language via the internet.”

The 2010–2020 section of the Bi Pan Library collection glows as a bold and unapologetic era of fluid literature; it gave us Shiri Eisner’s radical modern classic (perhaps the most recognizable bisexual book ever published) Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, a masterful balance of actionable bisexual theory and accessible writing that welcomes people who are new to the ideas. Kate Harrad’s anthology Claiming the B in LGBT: Illuminating the Bisexual Narrative covered vast ground with chapters on race, disability, gender and non-monogomy. Books that enthusiastically embraced the variety of words people use for plural attraction also began cropping up more frequently, like Karen Morgaine’s artful Pansexuality: A Panoply of Co-Constructed Narratives and Faith Beauchemin’s very tiny anthology with a very large name, How Queer! Personal Narratives from Bisexual, Pansexual, Polysexual, Sexually-Fluid, and Other Non-Monosexual Perspectives. The diversity of language Janet Bode first spotlighted in the ’70s blossomed with the ability to connect with like-minded people and to learn about a universe of queer language via the internet.

This is an aspect of Shaw’s Bi that may not age well, in the way many books about sexuality, gender and identity naturally fade in relevance over time. Shaw commits to using the term “bisexual” or “behaviorally-bisexual” through the whole book, simplifying the language of plural attraction in the way of a researcher establishing clear vocabulary for a study. But condensing queer language can come at the cost of erasure. In nearly all the books I’ve mentioned so far, people who use words like pansexual, omnisexual, fluid, etc., have had their experiences included in research or storytelling, but their identities painted over, in the end, with the word bisexual. In the future, we might look back on concepts like “the bisexual umbrella” or “bi+” the same way we look back on titles like Bisexuality and Transgenderism, which was the first book about fluid sexuality in the trans community. The phrasing made sense to us at the time, but give it another decade and it would never go to print. Queer language is an ongoing process of building and balancing; rebuilding and rebalancing.

We are gearing up for an exciting new decade of sexually fluid literature in the 2020s. Just last year, psychologist Ritch C. Savin-Williams published the first book to focus on bisexual, pansexual and fluid youth, and fellow U.K. author and bisexual activist Lo Shearing released Bi the Way: The Bisexual Guide to Life. At first, Bi the Way looks like it might cover the same ground as Bi, but between the two pink-purple-and-blue covers are very different books. Shaw’s book lays out the story of how fluid sexuality has been perceived scientifically and socially, with a bit of personal storytelling for flair, while Shearing filled Bi the Way with advice about the everyday ins and outs of being bisexual, with a bit of history and social science woven in between. These are complimentary conversations that serve different purposes. Shearing also announced in 2021 they are editing a bisexual anthology with fellow bisexual activist Vaneet Mehta, ensuring the tradition of bisexual storytelling will live on.

What the publishers who rejected Bi didn’t understand is that sexuality and gender are ever-shifting, ever-expanding topics. We will never be done talking about being bisexual, or pansexual, or omnisexual, or fluid or whatever brand-new words we embrace in the future. When Bi hits bookstores (June 2 in the U.K., June 28 in the U.S.), it will provide a Bisexual Research 101 course for a fresh audience of international readers (her book is already making publishing history in Germany, where it was published in translation in May) and my library shelves will be one book richer.

What conversations will we have next?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra