I was 15 when I first drank liquor, a drink with a whopping 0.5 percent alcohol content. This was a deliberate choice: It made grieving my first teenage heartbreak more dramatic. At the time, I was still grappling with my identity and trying to act like my straight male peers, so I pursued a classmate, who I found pretty. She agreed to become my girlfriend for a trial period of sorts to see if we’d work out. We did not. We didn’t even make it a week.

I buried this memory for years. It wasn’t until I read John Paul Brammer’s new book, ¡Hola Papi!: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons, a memoir based on his widely popular LGBTQ2S+ advice column, that I thought about it again. Unlike his column, the questions in Brammer’s book come from his own experiences and are used to anchor themes including growing up, coming out and understanding relationships.

In the chapter “How to Kiss Your Girlfriend,” Brammer recalls his relationship with his first girlfriend Rebecca, which was filled with teenage awkwardness and confusion. He explores ways of reconciling years lost in the closet using the story of their relationship. The dilemma is familiar: What do you do when you genuinely care about someone but you’re also trying to understand yourself?

They eventually broke up, but Brammer writes: “I don’t want to see our relationship as a failed experiment or a sad attempt at hiding who I really was. I want to include that time, the good and the bad, into the project of my life. I want to be happy when I think of the times Rebecca made me happy.”

This resonated with me. I came out as gay years after the night of my first heartbreak. Looking at that memory through today’s lens, it’s easy to dismiss it as childish, and my inner sassy gay commentator wants to raise his eyebrows and say, “Sis, really? Choices.”

But both of these reactions lack nuance; they’re flippant takes that undermine real emotions. I know my ex (if I can call her that) and I would have never worked out as romantic partners, but the pain I felt that night more than a decade ago was real. It did not go away just because she was a girl and I later came out as gay.

It turns out I wasn’t the only gay man to have made a youthful attempt at heterosexuality—or to have the urge to make light of it. In his book, Brammer explores gay men’s tendencies to reduce women and “cast their bodies as jokes or as failed attempts on our sexual liberty because we think that’s a small revenge on the straightness that was unjustly imposed on us.” He ends the chapter having found peace with the thought that, at one point in his life, this person made him happy.

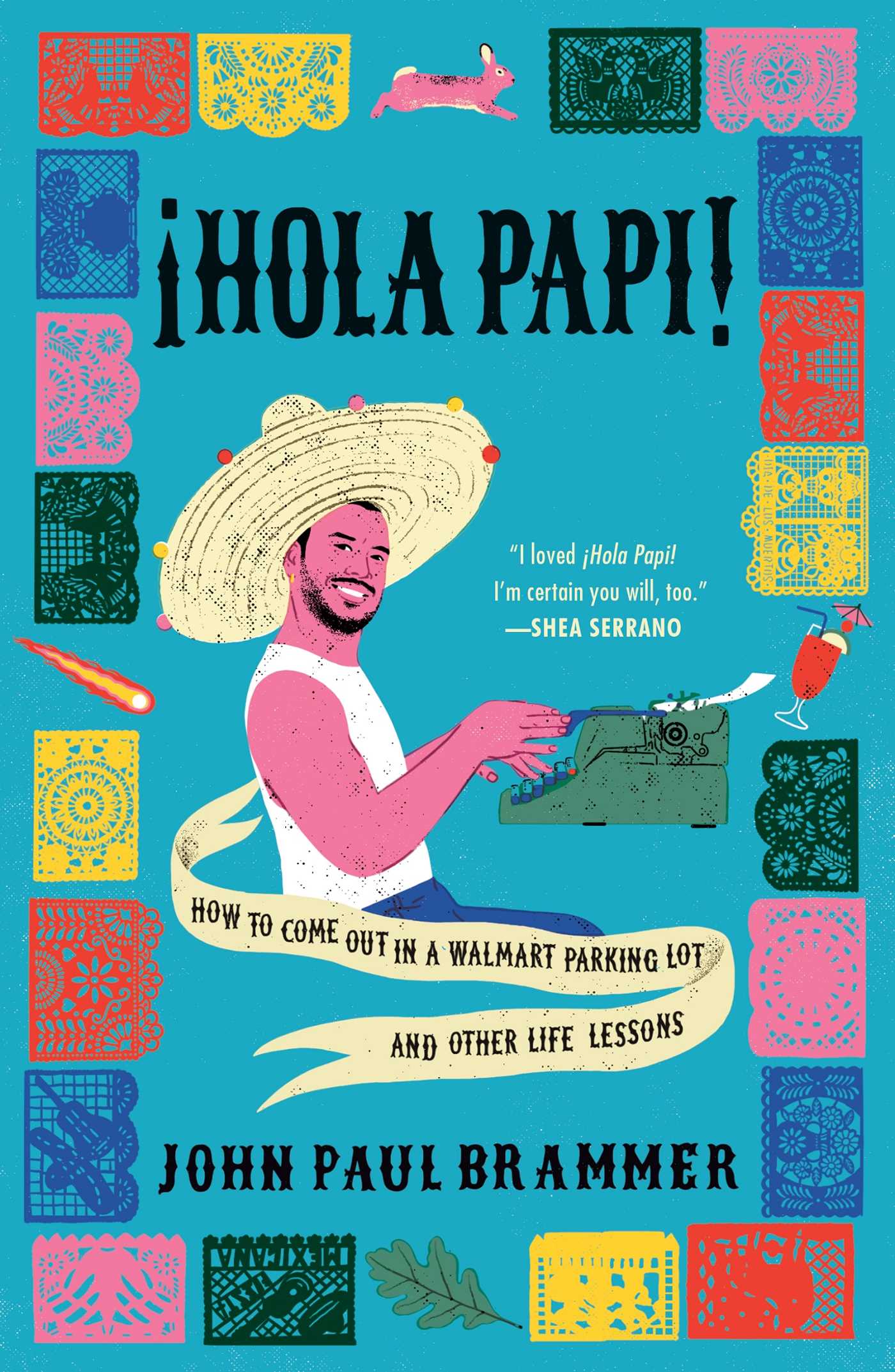

Credit: Simon & Schuster

Like Brammer, I find peace in the memory of liking an amazing person and how it was the easiest thing to do at the time. Reading ¡Hola Papi! is similarly fulfilling; it’s always powerful to realize you’re not alone. Brammer’s writing confirms that someone actually gets it. It’s a comforting thought—and while it may sound contrived, I have an advice column to thank for that.

I doubt I’m the only one who feels this way. ¡Hola Papi!, which started out in 2017 as a kind of “Dear Abby” parody for the LGBTQ2S+ publication INTO, has become one of the most popular advice columns anywhere (it currently lives in newsletter form on Substack). I reached Brammer via video call at his home in New York City to talk about ¡Hola Papi!, his writing process and finding humility in silence.

First things first, ¡Hola Papi! has fun and warm cover art (illustrated by Sonia Pulido). What’s the story behind it?

As a visual artist, I’m really into the visual vocabulary of melting a story down into one symbol. I wanted the cover to have symbols [including a comet, a rabbit and an oak leaf] referencing some of the big chapters in the book. I realized when I was writing it all down and sending it to my publisher how busy it was sounding… but that’s sort of what ¡Hola Papi! is: it’s very busy, it’s very fun. It sorts of winks at the reader. I wanted something that kind of carried that wink aesthetically into the book. I wanted to stay true to the column, I want to stay true to the voice.

What was the process of writing the book, given that it’s so raw and personal?

I was very much inhabiting myself and my voice. When I’m writing ¡Hola Papi! columns, I can sort of feel it mentally, when I make the switch into that character. I start writing from a very confident, very pop, very funny kind of voice. It’s just like being a cartoon character. So to that degree, it gives me some armour whenever I need to discuss difficult things. But with this book, I really did see it as the inverse of ¡Hola Papi!. This book is my letter to the world. It’s my turn to write a letter and send it out.

What does it feel like writing about your own life and reliving experiences, all while trying to answer people’s questions?

It’s been strange. The whole book is sort of about me wrestling with this identity of “who am I to be answering anyone’s questions, because I don’t know anything.” It was really easy at the very beginning, because ¡Hola Papi! started out as a parody. Humour is a landscape that I’m super comfortable with, it’s sort of my reflexive crutch.

But with the book, and also the later columns, I realized that you can’t just be a parody all the time—especially for what I was trying to do. Some of these letters are just not funny. I can find ways to put humour in my response, but the situation at hand doesn’t call for just me being a clown the whole time. I had to start taking them seriously, and it was that seriousness, or the call for it, that really got me thinking about my life. They got me thinking about what my credentials were.

Thinking about how I might be a gay mentor to someone else, and then trying to justify to myself over the course of several chapters, saying, “Oh, but these are the life lessons you learned. These are the hard things you’ve overcome. These are the stories that make you who you are, and make you someone who can give someone advice.”

And then, in the end, still realizing, “No, those things don’t all cohere into an ability to speak to this person’s issue.” It ends with me not answering a letter. So it is sort of an obligation to the community. It’s about wondering what authority is, it’s about wondering how reliable of a narrator we are to ourselves. It’s messy, and there’s no clear cut answer, which is what I really love about the book.

You also talk about listening rather than speaking. Why is this important, especially when talking about LGBTQ2S+ people and their experiences?

One of the great privileges of running this column has been receiving letters from people whose experiences I don’t materially share, but who have given me glimpses into their lives and sort of talked about their experiences in a way that has felt very intimate. This felt very informative to me.

It’s just been so cool to have people trust me in that way and talk to me in that way. What I do with that later is really important; it matters a great deal. In the book, for example, me ultimately deciding “no, I can’t help this person because that could do more harm than good” I think is a result of listening.

It’s the result of being like, “No, I don’t need to take up space here. I don’t need to tell someone what to do in this situation. I’m not the voice that’s required here.” It is super important. Under the umbrella of LGBTQ we have every gradient of experience: we have issues with citizenship, misogyny, colourism. We have all these things going on within our little loose conglomeration of people. You’re gonna have to listen if you’re going to want to be a good neighbour.

In the chapter “How to Be a Real Mexican,” you said you used other people’s pain to validate your identity. Can you speak more to that?

I feel very critical of this country, I feel very critical of racism and I feel very critical of its policies. Whereas my abuelos [grandfathers] were very much bearing the brunt of that systemic injustice, and yet had very different beliefs from me. So trying to juggle all these things, trying to feel like a really valid extension of their identity in some way (which is what I wanted to be), I found that very difficult, because the reality is, I didn’t suffer like they did.

I sort of considered pain and suffering to be the missing ingredients. As I’ve gotten older and I’ve met more people, I’ve realized that it doesn’t have to be that way.

I’m curious, what was it like reliving painful memories of bullying and heartbreak for this book?

If I’m writing about something and I’ve got it out on a page, it means that I’ve dealt with it, or it means that I’ve settled on the narrative about it. You could not pay me all the money in the world to write about something that I still feel that I’m wrestling with or haven’t come to peace with or come to terms with. That’s not saying that my understanding of the subjects presented in the book can’t shift or that they can’t change. It’s more just like, when I was writing it, it means that I have a story about it that I’m comfortable with, that I know really well, that I’ve traveled a lot in the circuits of my brain and I can now put it out there.

You also explored different faces of love in this book as personified by your almost boyfriends: Corey, Thomas, Stefan, Lukas. How do these relationships mark your growth as a person?

I think in writing about those and exploring those, we can learn a lot about ourselves, how we see ourselves, how we see other people, what we want out of other people, what we want out of life.

You also talked about Carlos, who was abusive to you. We rarely hear stories about sexual assault within the LGBTQ2+ community. Why did you decide to include this story?

I would say out of all the chapters, this one was the trickiest one to do. It was the hardest to handle, because I knew what I wanted to say and I knew that saying it in the way that I needed to was going to be hard, because I didn’t want to just be like, “Carlos was an evil person. This horrible thing happened to me and therefore, here’s how I’m trying to deal with it.”

I don’t think that really reflected my feelings or the actual situation. What I absolutely wanted to avoid was saying that this is, in some way, my fault; that I deserved it in any way, that I put myself in a risky situation and therefore this was the outcome. I completely want to avoid that while also not sacrificing all those weird nuances and ideas in my head that kind of kept me in his orbit.

I didn’t want to find an excuse for it or even feel the need to excuse it, I just wanted to put it all out there—the messiness, the weirdness—while also still putting out what I feel to be a really necessary narrative about how gay men can experience sexual assault as well. Men can experience sexual assault. It can happen in ways that don’t necessarily rely on pure physical intimidation.

It was a difficult chapter to write, but I’m really proud of it. I hope that if people read it—I know it might be hard for a lot of people to read—but what I’m trying to say in that chapter is you’re not alone. It happens more often than any of us are even aware of.

What do you want people to take away after reading your book?

I really should have thought of that question before I started writing it. When I was writing it, the book was just arranging itself. I knew what I wanted to say and how I wanted to say it and what I wanted the stories in the collective to communicate. It ends with reminding people that they are, to some extent, an author, and that they can tell the stories of their lives in different ways that they want to because they are stories, they’re narratives, and you’re a storyteller. I think there’s agency to be found there.

Whether or not people actually walk away with that sentiment isn’t up to me. I think that there are a lot of different things to be gleaned from all the different stories. If you were to read them just individually, you might come away with different lessons or different thoughts, different feelings.

I’ve really been wondering how to express my desires or hopes or dreams over other people’s reading experience, because I’m just like, “Oh my gosh, there’s gonna be so many different kinds of readers in this book, and who knows what they’re going to take out of it?” I think that my meager hope is that you take something out of reading it and that that something can be either useful or comforting or funny, or it can just get you through a flight. That would be nice to me.

¡Hola Papi! started because people used to say that when they interacted with you on dating apps. What do you tell people who send you “Hola Papi” now?

Whenever someone sends me “Hola Papi!” on Grindr now, I’m like, “Oh, you follow the column?” And they’re like, “What? Column?” It’s just funny to me.

I love the lore behind ¡Hola Papi!, I love that it started out as this moniker that people would send me and I just turned it around and embraced it. I think that that’s the way to live life. It’s like, if it’s happening to me, I should at least make something out of it. Now it’s a book. That’s how carried away you can get with something.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra