The early internet was held out as the great equalizer, a utopic space where borders could be crossed and bridges erected. But looking at the digital landscape that we inhabit today, we might be wondering—who missed the memo?

To be fair, being online can be great for queer folks. In my own experience, YouTube’s corpus of coming-out videos offered a number of useful scripts that I would later follow. Digitally born fanfics gave me alternative narratives of what gay superheroes could look like. A favourite website currently, Queering the Map, encourages a sense of queer community and global citizenship. And, at the same time, my entire brand of humour remains an archived feed of Twitter gays circa 2017.

Digital innovations have led to a wide range of benefits for queer folks, but they’ve also produced an evolving set of online harms. By that, I’m referring to content, communicated over the internet, that creates physical, psychological, emotional or financial harm to the subject or recipient of the content—or to society, more broadly. This definition, paraphrased from a recent national survey on online harm, was one of topics up for discussion at the second annual QueerTech Qonference. The conference, which took place earlier this month in Montreal, focused on career development, community support and building resilience.

I had an opportunity to talk with one of the conference panelists, Sam Andrey, to discuss the insights he imparted during his presentation: “Online Harms in Canada and Their impact on 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians.” Andrey is the managing director at the Dais, the public policy think tank at the Toronto Metropolitan University, responsible for the survey mentioned above. This is the fifth year that the group has conducted a national survey to gauge Canadians’ attitudes around online safety, but it’s the first year that the study—derived from over 2,000 participants—included a large enough sample of LGBTQ2S+ respondents (about nine percent) to merit a look at how queer folks’ attitudes and experiences of being online compared to the rest of the country.

My overall sense in speaking with Andrey, whose background in public policy and academia has garnered him a clear expertise on his subject, was a sense of vindication. Andrey, himself, phrased this much better than I was able to as he reflected on his experience at the conference. “At QueerTech, I think it was putting numbers to a thing that everyone kind of understands and knows, but there’s something validating in seeing it quantified.” Similarly, I found that there was something validating in hearing Andrey’s thoughts on where we ought to go from this far-less-than-utopic hyperspace that we’ve created. While offering a handful of suggestions as to what we might do as individual users of social media, Andrey’s larger takeaway from the survey is that new infrastructure is necessary.

Earlier this year, you put out a study called “Survey of Online Harms in Canada.” What was the impetus for this work?

When we first began working on these issues it was post-Trump, post-Cambridge Analytica, post-Brexit. There was a lot of talk in Canada and around the world of how these social media platforms could potentially shape democratic outcomes. Obviously, a lot has happened since then, but that was the genesis.

At QueerTech, you presented on the online harm that LGBTQ2S+ folks face in Canada. Can you tell me more about these concerns?

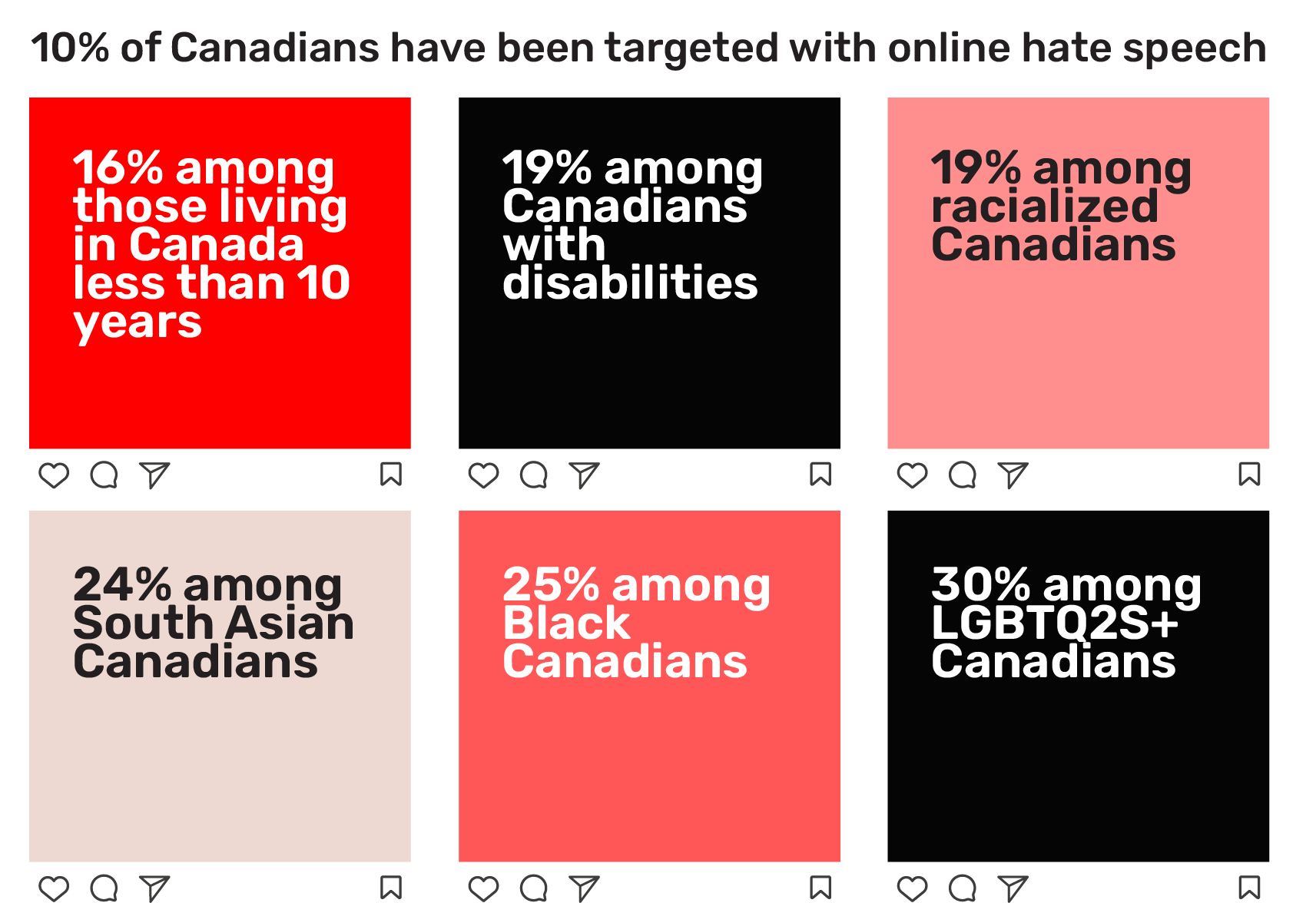

Canadians online are seeing and experiencing hate and harassment at significant rates, but queer people experience those harms at about twice the rate of Canadians overall. We found that 10 percent of Canadians say they’ve been personally targeted with online hate speech, whereas that’s 30 percent for queer folks—three times as high. Eight percent of respondents said that they’ve been targeted with online harassment that caused them to fear for their safety, and that number was 17 percent among queer Canadians. So, in general, there are higher rates of exposure and personal experiences with harmful content for queer folks online.

Queer people, in general, are more online than non-queer folks. Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and Snapchat all have significant margins of between 50 and 100 percent higher rates of usage than non-queer Canadians. I think it’s a reflection of part of a younger demographic, but also a lens to put on this; queer people are more connected online.

Credit: dais.ca

The survey found that participants largely felt as though online platforms like Facebook and TikTok should be responsible for fixing the issues surrounding these online harm. Is this your sense as well? What would that look like?

In Canada, there’s currently a debate about whether to do something on the government or regulatory side—basically, the question is whether or not we should put responsibilities on these companies. Right now, it’s essentially at the company’s discretion how to deal with these challenges.

For example, we asked Canadians how much they trust these platforms to act in the best interest of the public, and people generally have very low trust in social media platforms. Facebook, Twitter and TikTok are the least-trusted organizations when we asked about a whole variety of companies (for example: oil companies, telecommunication providers, mainstream media) just to give people a barometer of where social media stands. And social media stood at the very bottom.

So we’re starting from a bad place of trust, but when we asked people about government intervention—at least for Canadians—it’s about two to one, so two Canadians favour intervention for every one Canadian who is more cautious about protecting freedom of expression. It’s a clear majority, but it’s not an overwhelming one.

There’s a lot of nuance to how people feel, but in general, I think more Canadians than not favour some requirements around regulatory scrutiny and transparency on these platforms.

Are there ways that users, on an individual level, can contribute to decreasing online harm? Is focusing on our individual responses even a useful way to think about some of these larger issues?

We asked people if they had ever reported illegal activity to an online platform—if they’d ever tried to block or report something—and 43 percent of queer people said they had done so. Interestingly, they report that it’s largely effective. Only 28 percent said that their reporting was ineffective; most thought that it was either moderately or very effective, so that’s a feature that’s largely working for people.

When it comes to blocking and reporting, I’d say to do that liberally. When you’re seeing hate speech or harassment targeted at other people, reporting is something that the individual can do. This may be obvious, but choosing the community that you’re interacting with is important. Do you want to have a public profile? Do you want to be friends with that person? For some users, even asking those questions aloud can help them make different decisions online.

On a more regulatory side, one of the proposals that is currently being entertained is the idea of an ombudsman. A lot of these big media platforms are impossible to penetrate; you submit a report; they respond that it doesn’t violate their terms of service, and you’re just kind of left with nothing. You wonder if a human ever interacted with it. So one idea that’s been pitched is an ombudsman who can advocate on the individual level with social media platforms, but who can also see patterns and things emerging that they could try to highlight, drawing attention to specific problems. There’s something about that idea that I quite like.

I tend to go regulatory, but transparency is very powerful. If these platforms are required to report, how many instances of hate speech are happening? How long are they taking to respond? How many are being appealed? Most of these are public companies with shareholders. There is power in requiring transparency because it becomes a motivating factor to improve.

Are digital spaces getting better or worse for queer folks? How optimistic are you about the future of the internet?

On a pure numbers basis, the proportion who say they were frequently hit seeing hate speech has fallen modestly, so it went from 48 percent in 2019 to 41 percent last year. Just based on that, you could argue that it’s gotten modestly better. My own view of it, based on other sources I’ve seen and even anecdotally—as I see how many of the big platforms have been behaving—I think systems like Meta’s platforms [Facebook and Instagram] and YouTube have been taking faster action, developing better automated systems.

Twitter, post-Elon, has certainly regressed in its enforcement. In general, the volume and viciousness of anti-trans hate speech has gotten worse, largely because of the conditions in the U.S. that have bubbled up to Canada. You mash all that together, and are things better or worse? Maybe worse, or worse in different ways and better in some specific ways.

But I’m not feeling good about it. Still, there are lots of ways to improve.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra