Credit: Adam Coish

Angela James feels mixed emotions when she thinks back to her early years on the ice at North York’s Flemingdon Arena.

It’s where she got her first taste of competitive hockey. It’s also where she had her first major brush with sexism when, at eight years old, she was kicked off the community centre’s all-boys team despite being the league’s leading scorer.

No hard feelings. After all, the building was renamed the Angela James Arena in 2009.

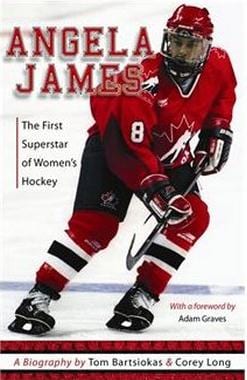

This is just one of many stories in a new biography entitled Angela James: The First Superstar of Women’s Hockey. Released in late August, it chronicles the journey of arguably the best player in the history of women’s hockey. James also happens to be an out gay woman.

In recounting her life, Tom Bartsiokas and Corey Long outline the events that led to the surge in popularity of women’s hockey. James’s sexuality is not front and centre but rather taken as a matter of fact.

“Who I am is who I am,” she says.

From the early 1980s to the mid-’90s, James was a dominant player in women’s hockey, often referred to as the female Wayne Gretzky.

She was known for her physicality; her strength intimidated opponents and helped change the impression that women’s hockey isn’t tough. Looking at her powerful build today, it’s no surprise rivals once cringed at oncoming body checks.

James was the leading scorer of the Central Ontario Women’s Hockey League for eight seasons. She was selected as MVP at the national championships an unprecedented eight times and won four world championships.

“I don’t think a lot of people realize how much of a trailblazer Angela was in women’s hockey,” says Phil Pritchard, vice-president and curator of the Hockey Hall of Fame. “She was as good as any player that ever played.”

James is the daughter of a black American father and a white Canadian mother. She was raised alongside two older half-sisters from her mother’s side.

The kids grew up in government-funded housing in Flemingdon Park at a time when few black people lived in the community.

“I didn’t really think of myself as black because my family was white,” James says.

She recalls a few instances of racism as a child but says, for the most part, neighbours were friendly.

“I didn’t really experience a lot until the more identifiable black people started moving into the community,” she says. “Then it was, ‘Well, you’re not black, like me, and you’re not white, like them. What are you?’”

Playing hockey as a child, James occasionally heard racist comments from parents in the stands. Throughout her playing years, she also faced racism from opponents, but she didn’t turn the other cheek. “I had my fair share of fights and scraps to make sure that I stayed above water.”

She says her race was never an issue for teammates.

At 16, she was accepted into Seneca College, where she later set scoring records playing defence, though she spent most of her playing career as a centre. She graduated in 1985 and was hired on as a sports coordinator for the school, a position she still holds.

She was later a member of the inaugural Canadian women’s national team of 1990 and scored Canada’s first goal in sanctioned international play.

In 1992, when the International Olympic Committee announced that women’s hockey would be part of the 1998 Olympics, James was thought to be a shoo-in to make the cut. It was not to be.

She was left off the team, and Canada, a favourite going in, won silver.

“I did my best. They felt that my best wasn’t good enough,” says James, who had Hockey Canada review her release, to no avail.

Her voice rises — she is obviously still bitter about the snub. “I think they’re full of shit, and I think a lot of people knew that as well.”

The 1999 Three Nations Cup was her last tournament for Team Canada. In the final, Canada beat the US three to two, in a game decided by a shootout. As the first successful shooter, James’s goal stands as the game winner.

She continued playing at a club level until she retired from professional hockey in 2001.

Her years in the game never provided her with a big payday. While she had a contract with Nike, no major money was involved. That remains the case for national team players, who receive only a stipend.

“It only made the love of the game that much stronger because we didn’t play for a living,” she says, smiling. “We played because we loved playing.”

She recognizes that few women play at the professional level today. Still, she believes the playing field is evening out.

“The support is there more for the girls these days,” she says. “They’ve come a long way.”

So has James.

In 2010, she was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto.

Along with American Cammi Granato, she became the first woman ever inducted. She was also only the second black player to receive the honour.

“It was a milestone in hockey,” Pritchard says. “She’s in an elite class of her own.”

In her induction speech, James thanked her partner and children for their love and support. Until then many fans didn’t know James’s sexual orientation.

She and her partner, Angela, have three children: Christian and fraternal twins Michael and Toni.

“There was no way I was going to deny Ange and the kids their opportunity to that night,” James says.

Until then, no openly gay athlete had ever been inducted into one of the major North American sports halls of fame. In fact, no current or former NHL player has ever come out.

“I think it was the timing of it all,” James says, referring to the accepting environment Toronto Maple Leafs general manager Brian Burke has been trying to instill in the hockey world. “I was very lucky because it could have easily backfired on me.”

Burke’s support for gay athletes intensified following the death of his gay son Brendan in a car crash in 2010. In March 2012, Burke and his son Patrick launched You Can Play, a project that combats homophobia in hockey.

“Brian Burke has changed a lot of the hockey world’s mentality in terms of homosexuality,” says James, who thinks it’s still risky for professional athletes to come out.

“It’s still not that safe for them. There’s still the initiation and hazing that takes place in all levels of sport.”

Male athletes have little incentive to come out, she says. “Hockey players, even though they love the game, have to look at it from a business point of view.”

In her own case, James says she was never in the closet; media simply didn’t ask about her sexuality. She believes the same goes for many lesbian athletes today.

There could be more to it. Patrick Burke says female locker rooms can be more homophobic than men’s.

“It’s sad and interesting to see that on the women’s side of things it’s either a complete non-issue or total and complete pandemonium,” he says.

James was one of the lucky ones. She says teammates knew about her sexuality and it was never an issue. She says she also played with other gay women, but the majority were straight. “A lot of people might think the opposite,” she jokes.

And while for most of her career she decided to keep her private life just that, Burke says that she has been a “wonderful role model for athletes and non-athletes.”

Today, only strangers aren’t aware that Christian and the twins have two mommies. Whether it’s visits to school or when James coaches her eldest son’s minor league hockey team, there’s no hiding.

That’s just fine by James.

“If you can’t be yourself, then you’re just living a lie.”

Angela James: The First Superstar of Women’s Hockey

Tom Bartsiokas and Corey Long

Women’s Press Literary

$14.95

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra