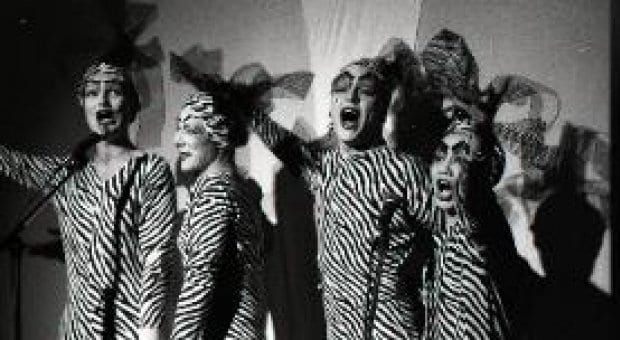

"It was so of that moment," says (queer)intersections curator Christine Stoddard of the grunt's Halfbred cabaret series in the mid-1990s. Credit: grunt archives

Vancouver has a reputation (at least among those of us not born here) for playing hard to get. A diverse range of political and artistic communities has long thrived here, but they aren’t always easy to find.

A new series of online exhibits called Activating the Archive, from the grunt gallery, aims to draw out the vibrant histories of often marginalized groups and reacquaint Vancouver with its often radical past.

Interdisciplinary artist and scholar Christine Stoddard curated one of the exhibits, titled (queer)intersections.

The exhibit, made up of essays, video and photos, focuses on queer identity politics expressed through performance art in the 1990s.

“The ’90s for me was really when that notion of queer started to emerge as a political and identity category,” she says. “It’s taking the lesbian/gay movement and way of thinking about your sexuality and identity, and kind of opening it up to a less rigid category.”

Stoddard came to Vancouver toward the end of the 1990s, moving here with her first girlfriend to do a master’s of fine arts at Simon Fraser University. She got a job at the lesbian bar Charlie’s (“Oh god, I was a terrible server!”) and started to meet women who were also interested in exploring queer feminisms and with whom she would perform.

“That was the first time I really felt like I belonged here. It sounds sort of cheesy, but it’s true, I did.”

At the time, she says, she didn’t consider herself a very radical queer. She grew up in the relatively small city of Halifax and says she was just looking for some kind of reflection of herself.

When she came out to her parents as bisexual, they had a hard time understanding, she says. They probably would have had an easier time had she used the word gay or lesbian, she reflects.

“It does confuse people when you don’t fit into a nice delineated box.”

She thinks the word queer would have posed even greater problems. “I was just discovering the language around queer theory myself and I hadn’t really thought about that term as a way of identifying myself, and if I had really understood that at the time I think it would have been even more confusing.”

Now, she says, “queer” does a better job of encompassing her experiences of sexual and gender fluidity.

Performance lends itself particularly well to discussing the intricacies of the word queer, Stoddard says. With the artist physically present onstage, it can often feel more autobiographical than other media. With a live person in front of them embodying the idea of hybrid identity, the audience has little choice but to acknowledge it.

“We aren’t just one thing. And who is excluded from that category of gay? Who’s not seen in that category? ‘Queer’ allowed people with alternative sexualities to talk about some of those places those intersections occur. Identities that were on the border of the categories could start to speak about their experience.”

TL Cowan, a writer, performer, activist and professor now based in New York City, came of age in the feminist spoken-word poetry scene in Vancouver in the 1990s and contributed an essay to (queer)intersections.

Performance art was not just about recognition, Cowan says. It played a crucial role in self-creation as well.

“I think that performance art, in particular cabaret as a performance-art genre, served and continues to serve an important radical pedagogical function,” she says via email from New York. “In these experimental spaces we have had our understandings of what constitutes feminist and queer space, politics, desire, bodies, et cetera.”

Performance art was at the time, like many of its performers, itself a hybrid. It incorporated elements of theatre, dance and standup comedy. Stoddard sifted through hours and hours of film and video (some of it of admittedly poor quality), giving her a chance to reexperience the work and bring it to a new audience.

“You can still get a sense of the liveness of those issues, of the real passion behind them,” she says.

One of the grunt’s key performances came midway through the decade. Halfbred was a series of three cabaret nights focused on particular hybrid identities: miscegenation, bisexuality and transgenderism.

“The Halfbred program, to me, was a historically important kind of moment in Vancouver’s queer art history,” Stoddard says. “It was so of that moment. Those were the kinds of discussions happening in academia; those were the kind of politics happening on the ground.”

The program was, in some ways, a crystallization of everything the grunt gallery was doing at the time, drawing on race, gender and sexuality and recognizing the myriad ways there are to construct and perform composite identities.

“The word makes you think half breed, half Indian, half white,” Stoddard says. “That’s what it makes me think of, but the way the curators of that festival worked through that idea, it wasn’t just about First Nations identity at all. There were numerous approaches to being half or hybrid.”

Representing as many of those approaches as possible was foremost in long-time program director Glenn Alteen’s mind when he put the show together in 1995.

“It wasn’t just around being bisexual and transgender. It was also around being from any of the ethnic communities and being gay and trying to relate that to a stereotype of gayness that was very white and middle class and that left a lot of people out.”

Performance is the ideal medium to reflect the margins, Alteen says. “As a form it has an incredible amount of freedom, and I think for people who are marginalized that freedom to speak in their own voice, which is very different from reading lines from a play, became very important, especially in that era.”

To Alteen, bisexuality is almost more a condition than an identity. “It doesn’t really give you a world view in the way that being gay gives you a world view,” he says. “Bisexuality is, in some ways, all about passing. That’s the main thing about it: who sees you as what.”

He says that it’s an interesting position to be in and that often bisexual people endure less discrimination than other sexual minorities, but in some cases face more from within the queer community itself. “It’s a very odd situation you’re put in with the culture because, on the one hand, you’re viewed as kind of opportunistic in a certain way and, on the other, you’re also never quite trusted. You’re always stuck between these two.”

He adds wryly, “I never went out with a woman who didn’t think I was gay, and I never went out with a gay guy who was convinced.”

Alteen believes one of the most remarkable things about Halfbred is its continued relevance.

“In the mid-2000s, a young trans girl going to Emily Carr [University] said that finding Halfbred was hugely influential to her whole development and her whole journey, and I thought that was incredible because a lot of the time our exhibits aren’t relevant a year later, much less 10 years later.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra