Picture it: Christmas Eve. A chill blows outside, but inside the only trace of a shiver comes from the cold bottled beer that men clutch while chatting in groups. Frequent bouts of laughter break out as one man slaps another’s back in jollity. Pop Christmas carols — upbeat tunes like “My Only Wish” by Britney Spears and Mariah Carey’s “All I Want For Christmas Is You” — play over the speaker system, competing with conversations. Decorations — large boughs of artificial greenery aglow with lights — illuminate the otherwise dim room.

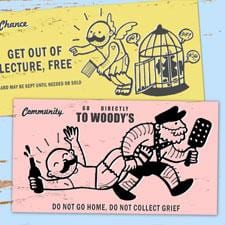

It could be a customary Christmas Eve celebration except that the characters are friends, not family, and the venue is Woody’s, not the family home.

That so many congregate in the bars at Christmastime is evidence that the holidays don’t unfold like a Tricia Romance portrait for many Toronto queers. Either by choice or exclusion some don’t participate in traditional family Christmases and many who do make the trek home grit their teeth, burdened by anxiety.

From varying degrees of familial discrimination to incongruent religious beliefs to the results of excess alcohol consumption, Christmas can be a Nanaimo bar recipe for disaster.

“There can be a whole stew of emotions,” says David Rayside, professor of political science and sexual diversity studies at the University of Toronto. “It’s still more likely that gay men and lesbians, or anyone different in sexual terms, are going to have strained relations with family members and are more likely to be in a relationship that doesn’t resemble relationships that other people are in. It’s compounded by the artificially pumped up set of expectations around jollity and contentment this time of year.”

Rayside isn’t surprised that what he calls “Christmas refugees” gather together at spots like Woody’s in place of or to seek relief from family. “Given a part of the holiday is centered on the traditional family… for those who aren’t fully accepted there’s an undercurrent of disappointment that is hard to avoid given the compulsion of most to attend at least one major family gathering.”

Rayside says he and his partner spent years attending their respective family’s Christmases, neither welcome at the in-law’s. When Rayside’s partner’s mother died the couple wound up at mama Rayside’s with rules as obvious as the Christmas tree. “There was the expectation to be part of the family but under a coded understanding not to make a fuss because there are lots of false hopes at Christmas.”

“I hate Christmas,” says Tom Wright. “I’d love to sleep right through it.” The 49-year-old Torontonian hasn’t been invited to Christmas with his family in Niagara Falls since coming out more than 20 years ago and his gloomy childhood memories of the holidays include heated arguments between parents.

“I already told work to keep me in the back room,” says the gruff Loblaws employee and 2006 Toronto Mr Leather Fellowship. Wright says Christmases improved during his brief marriage in his 20s during which time he had a daughter.

She stopped speaking to her dad in 2005 — a separation Wright describes as “a void in my whole existence” — but the two recently reconciled, spurred by Wright’s upcoming relocation to Halifax , Nova Scotia where his partner has been transferred.

“I missed her so much and I’m so grateful she’s back in my life,” Wright says. “It makes a big difference.” He hopes the reconciliation will help reignite his Christmas spirit but old habits die hard.

“I usually drink through the holidays and when I drink I start thinking of family and I get sappy and so it’s probably not a good thing,” Wright says. His partner Todd celebrates Christmas with more gusto while Wright mopes. “He puts up a tree and I don’t really get involved,” Wright says. “I bring him down and it’s not fair to him.”

This won’t be the year to break that pattern. Although his partner is already in Halifax, Wright is staying on in Toronto until their condo sells. “I wanted to make an effort to make this Christmas nicer but it’s not going to happen now that he’s gone. We have other years to make it happen, I just hope I can get it back.”

Kelly Maxfield, 23, is nervous about meeting her girlfriend Amanda Deschenes’ parents for the first time over Christmas. “I’ve met ex-boyfriends’ parents before but this is the first time I’m meeting parents of a lesbian girlfriend,” she says. The intro is a biggie. “Amanda’s the love of my life, my soul mate, so I’m really nervous to meet her parents because I want them to like me since we’ll be together forever.”

Maxfield, who moved to Toronto in 2007, met Deschenes in August while working a shift at Slack’s and they began dating in October. Although Deschenes has assured Maxfield that her parents are accepting of her sexuality, Maxfield is guarded. “I just don’t want to mask my happiness,” she says. “There is still a part of me that worries a little bit. I care for her so much that I don’t want anything to come in the way of that, especially at Christmas.”

Aaron Schuett, 20, has mixed feelings about the holidays. Schuett, who fled Alberta for Toronto this past summer, came out at 14 in December and says Christmas hasn’t been the same since. “My mother is very Christian and just doesn’t accept it. When I’m with her she ignores it and we don’t talk about it.”

The thought of his grandmother, more religious and outspoken, makes Schuett wince. “She’ll be on the attack,” he says. Grandma has been known to corner Schuett and ask when he’ll “begin following the Lord again.”

Schuett says he doesn’t plan to retaliate because “I don’t want to freak on her and give her a heart attack. I don’t want to ruin anyone’s Christmas so I’ll brush it off.”

He admits the reaction belies his pain. “It sucks because I have friends at home and in Calgary with parents who are fine with it and it sucks to have a mom who doesn’t appreciate who I am.”

The thought of bringing boyfriend of six months John Daniel home for the holidays evokes laughter. “That would be really awkward,” he says.

For Daniel, 42, to bring Schuett home to his Arkansas Christmas would be equally unwelcome where Daniel’s father is concerned. Daniel has opted out of the family Christmas for years. “I couldn’t be my authentic self and if you can’t be yourself, you’re not relaxed, comfortable or happy,” he says.

Instead he spends the holidays with friends and tries to reconcile his own celebration of the religious holiday with his family’s strict beliefs. “I pray but I don’t go to church,” he says. “I believe the basic goodness of the Bible is what people need to live by and it’s about being good to other people and doing the right thing.”

Christmas for Billy Gentile, 46, has been haunted by memories of Christmases past ever since the death of his parents. “I miss them a lot during the holidays,” says the George’s Play bartender. “They would always make a big Italian Christmas Eve dinner and I remember my mom always hung a string of Christmas cards in the living room.” His mother died 12 years ago from a heart disorder and his father died just two years after of Alzheimer’s.

Rather than returning to Cape Breton to spend Christmas with his sister he attends his partner’s family Christmas in Hamilton. “I really enjoy going to their Christmas but I think about my folks often.”

“A lot of us feel a tremendous sense of loneliness and it’s tough for those who are away without our normal support system,” says John Montague, a counsellor who caters to gay clients. He offers two considerations as homos venture home: planning and boundaries.

“Choose to spend your time with people you are going to be more relaxed with and avoid those with whom you aren’t,” he says. “If you can’t avoid them, make a plan.”

He suggests shortening your trip or at the very least the time you’ll spend with intolerant family members. “Don’t think that because you bought a plane ticket to Thunder Bay you have to spend the week or consider a hotel rather than the family home.” He also recommends calling friends back home for support.

“This is a time for rest and at least it’s a break from work so try to enjoy it as much as you can,” he says.

Montague notes that holiday hardships aren’t exclusive to the gay community. “The elderly, homeless, infirmed — gay and straight — are either alone or dependent at Christmas so across many ages and circumstances,

it can be a difficult time of year.”

Back at Woody’s, the bar’s associate general manager Steve Clegg observes, “People don’t tend to barhop, they’ll arrive and stay.

“We try to achieve a happy, celebratory place,” says Clegg, who worked Woody’s first Christmas Eve opening in 1989. “It wasn’t terribly busy that first year and was a little sad but it built rather quickly and into a much more joyous mood.”

Today Clegg continues to visit the bar at Christmas as a patron. “People use it as a meeting up point to see their chosen family on Christmas Eve before they head out of town or spend the day with their families,” he says. “There are also some who are not experiencing the best environments when they see their families and they want to feel welcome and included.”

Oftentimes Clegg’s bartenders are clamouring to work Christmas. “Some of them have family that are far or they don’t have good relationships with their families and they know the bar is a happy place,” he says. “They’re also good shifts. It’s not quite a rip-roaring Saturday but business is brisk.”

The camaraderie found on Church St Christmas Eve suggests Toronto homos have come up with their own antidote to the Christmas blues.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra