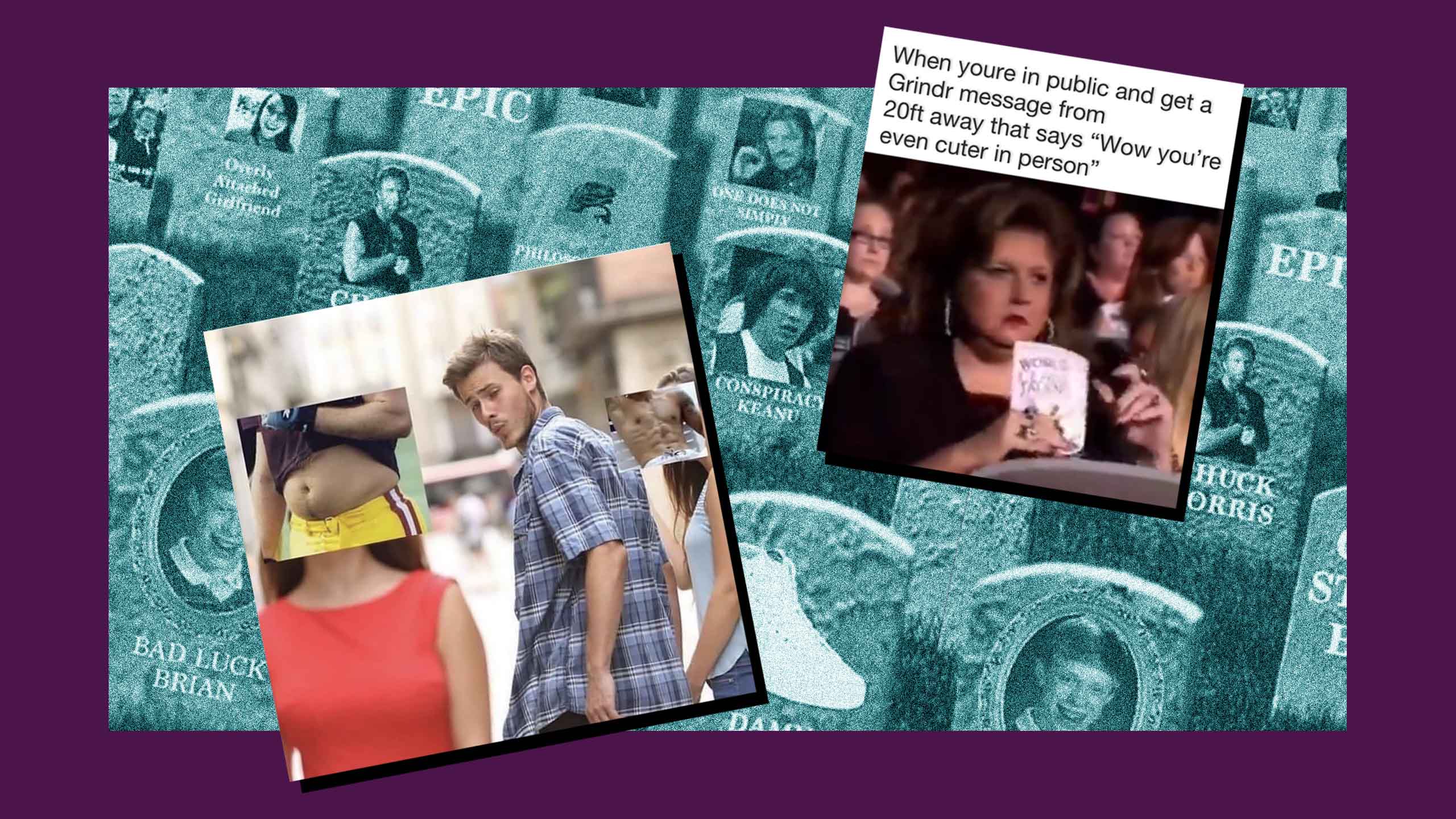

“Gay culture is knowing who this is and what is about to happen next,” announces a meme featuring gay porn star Griffin Barrows. A distracted boyfriend turns away from a set of six-pack abs to whistle instead at a passing dad-bod belly. Dance Moms’ Abby Lee Miller anxiously scans a crowd with accompanying text that reads, “When you’re in public and get a Grindr message from 20ft away that says ‘Wow you’re even cuter in person.’”

Advertisement

These exquisite memes all popped up on my feed over the past month, and I—the well-trained social media subject that I am—dutifully liked and shared these posts to friends who LOLed in return or (tactlessly) informed me they’d already seen it. And then, we all moved on, releasing the memes back into the depths of the internet. Yet, as I keep watching so many of these memes disappear, never to be seen again, I catch myself wondering, Where have all the good gay memes gone? It’s not that we don’t have just as many quality memes today; the examples above illustrate as much and, in fact, we likely have more today than ever. Still, today’s memes are becoming the stuff of ephemera at a quickening pace, quickly relegated to the meme graveyard of likes gone by.

Memes have been around for a while, but to define the viral sensation, the Oxford English Dictionary regards a meme as any “image, video, piece of text, etc. … that is copied and spread rapidly by internet users, often with slight variations.” Less well known, perhaps, is that this term, now so prevalent in online discourse, is rooted in biologist and writer Richard Dawkins’s work on evolution. In his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, Dawkins coined the term to describe “a unit of cultural transmission,” one that could travel from person to person. It’s no wonder why attorney and writer Mike Godwin began to use “meme” in the early ’90s to refer to online content that had similarly gained cultural traction.

In Godwin’s writing, memes often pointed to the worst internet trends. As he wrote in a 1994 issue of Wired magazine, “Memes are capable of doing lasting damage.” But while memes—like pretty much everything online—allow for both positive and negative uses, they’re more often discussed today for the way they bring together various communities online. As writer and reporter Kaitlyn Tiffany writes in her book Everything I Need I Get from You, which explores the rise of online fandoms, “The small thrill of understanding a meme comes from a feeling of belonging.” Elaborating on the idea, Tiffany observes that this dynamic is often intensified for queer folks online. In an interview published by Refinery29, the popular content creator Kate “Hina” Sabatine makes a similar observation. Reflecting on her own queer meme output, she notes that these memes “can be funny, but it’s also like, ‘Hey, we all kind of feel like that. Isn’t that kind of cool?’”

Know Your Meme, the go-to online encyclopedia for memes, offers clear evidence that the corpus is still expanding. It receives hundreds of meme submissions a week, so many that my browser quit on me every time I made it back a month or so into the site’s glitchy records. Based on submissions alone, there’s no shortage of meme production—although I was surprised by the lack of queer content I found on the site, especially considering claims like queer writer Lydia Wang’s that “all the good social media is gay,” drawing attention once more to the pivotal role memes can play in queer communities. Then again, scrolling through Know Your Meme’s submissions, there were only a handful that I even recognized; of those I did, none had made much of an impact. “How often do you think about the Roman Empire?” was a meme format that spread like wildfire, leaping from TikTok to Twitter to Instagram, before burning out just as fast. The “Mexican Alien Body” memes similarly read like a month-old time capsule. Hibachi Britney is bringing me all kinds of joy at the time of my writing, but I’m worried that it will be left to the dustbin of meme history within a week.

Contrast this to the staying power of so many earlier meme formats. “Bad Luck Brian” and “Leonardo DiCaprio Laughing” are essentially canon. And this canon has even been curated and gamified by the card game What Do You Meme?, which prompts players to pair well-known memes of yore with new captions in entertaining combinations. Elsewhere, the “Spider-Man pointing at Spider-Man” meme, in constant rotation since it appeared online in 2011, has made the leap into the Marvel Cinematic Universe, re-enacted by the actors Tom Holland, Andrew Garfield and Tobey Maguire in a publicity photo for the 2021 Spider-Man: No Way Home, before being explicitly referenced again in the 2023 Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

Truth be told, it’s a bit of a rush when favourites from the 2010s suddenly reappear on our feeds. “Is this a pigeon?” has become iconic. “Right in front of my salad,” a rite of passage. Even the “Distracted Boyfriend” meme format, noted above, is an old staple—made for easy queer remixes. It’s worth noting the difference between these tried-and-true meme formats (templates that can be recycled over and over again) and memes (the individual iterations of these formats). “Distracted Boyfriend,” for instance, is a meme format, while the “distracted boyfriend looking at a dad bod instead of abs” is one of the different memes that have resulted from that format. I suppose what I’m asking, then, is why our new meme formats don’t seem to be sticking the way these early examples did.

Part of this is likely due to the way these earlier meme formats have had time to canonize—to be absorbed into a broader cultural memory, recirculated not only in card games, but in meme-themed parties. Part of the allure for old memes might also come down to what Tiffany gestures to: memes are a means of establishing community online. For LGBTQ2S+ folks and other traditionally marginalized groups, knowledge of a shared past can help to bolster community. For some, this means a kind of nostalgia, a remembrance. For others, it’s a cultural inheritance, a means of learning a community’s history. In both cases, memes can act as cultural touchstones. “When years have gone by and the meme resurfaces, the feeling is also one of relief,” writes Tiffany. “It’s also an offer of reassurance—we all feel this way, still.” Reflecting on this quote, I view my past Google search into Jack Falahee after I stumbled across the “Uh, thanks, but I’m gay” meme as something akin to how I readily consumed My Beautiful Launderette when an older gay friend told me how informative it had been to him while he was growing up.

Contrast this long-loved film with today’s media that seems particularly designed for ephemerality. Social media algorithms reward those who can churn through content, as more content means more scrolling, and more scrolling means more engagement overall. The lack of enduring meme formats may simply be a sign of the times. The last decade’s memes, originating on Tumblr or Twitter, didn’t have to worry about the fleeting design of algorithms like TikTok’s FYP.

So, once again, while our longest-lasting memes might point to a sense of shared culture, what do our new memes point to? Is it that today’s memes cater to engagement algorithms rather than community? Is it that internet communities are losing their appeal? Neither of these suggestions seems very likely. If anything, the opposite is more probable. As noted earlier, memes—and especially queer memes—have only seemed to multiply. On Instagram, I follow no fewer than six accounts devoted purely to meme content (daddy_periodt, drinksforgayz, gaymeme.heaven, grindrmeme, itslitqueershit and thephagboy), and that’s just on one platform. Maybe the fact that today’s memes don’t rise as quickly to canon status is a good thing. It suggests a larger pool to draw from—and from which we might see more of our own particular interests and identities reflected. This means not only a move toward increased modes of representation, but greater plurality and more choices as well. Isn’t that a good thing?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra