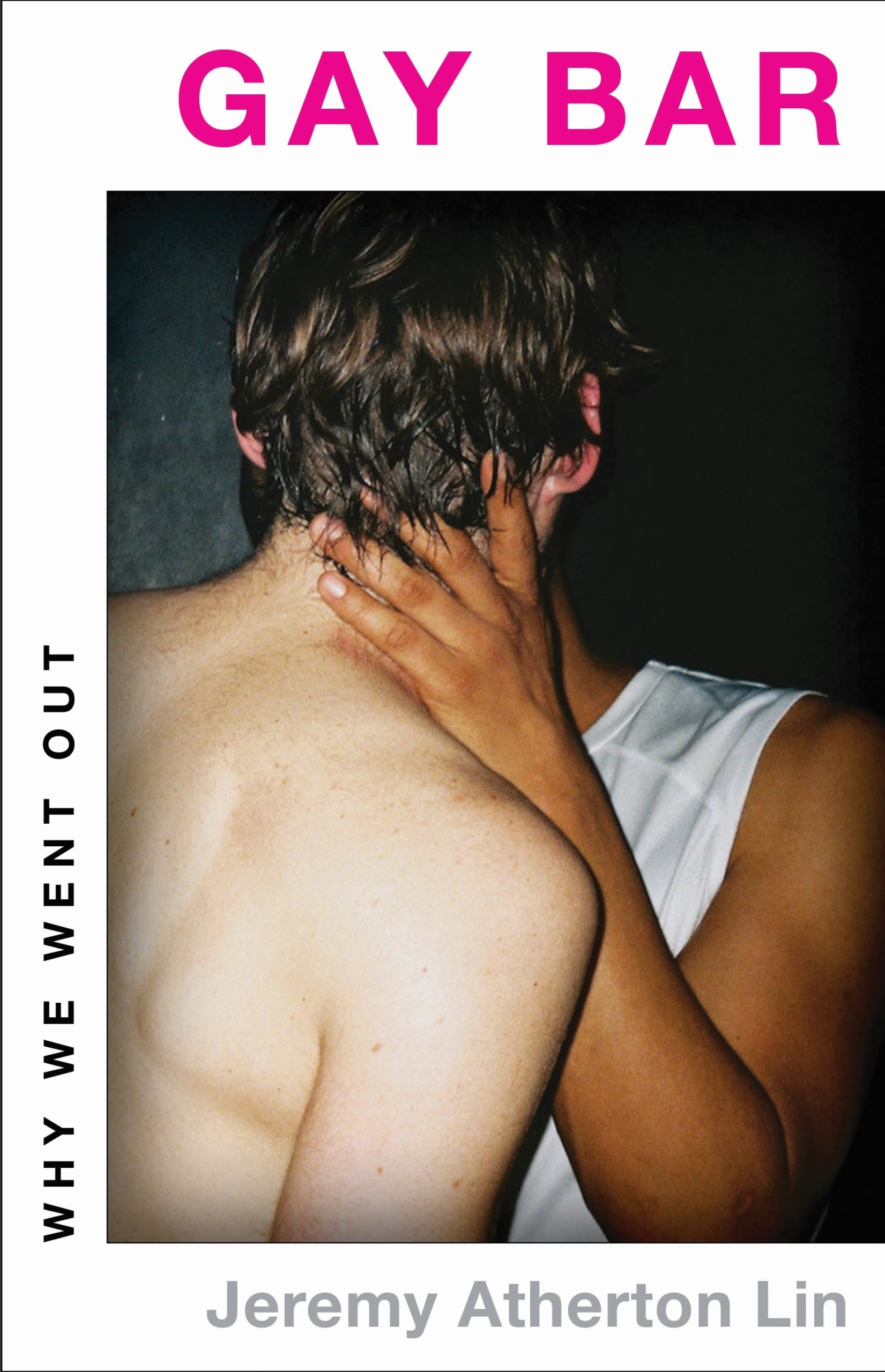

A mix of memoir, history, travelogue, anthropology and witty social observation, Jeremy Atherton Lin’s book, Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, reminds me, in the best possible way, of something that would have been on the front display in a gay bookstore back in the 1990s. That was an era when so much of gay publishing was devoted to intellectual magpies mapping a burgeoning new universe, with practices, traditions and sensibilities built upon male sexual desire.

Sharp and subtle, poetic and self-aware, Gay Bar has an impressive breadth of reach, with reports from celebrity-adjacent West Hollywood to the quirky resort town of Blackpool in the United Kingdom. But the perspective belong solely to Atherton Lin, an artsy, mixed-race Gen X gay man in a long-term relationship, American by birth but living in London. An essayist and editor at the literary journal Failed States, he also lectures at London’s Camberwell College of Arts.

Gay Bar is ambivalent about its subject matter: “Activists claim they should be kept open to facilitate knowledge passing between generations. Had I ever received wisdom on a barstool? Not really. Instead, I recalled a dive in Los Angeles that I’d timidly entered in my youth, only to be told You’re too good for this place.” Yet Atherton Lin’s curiosity finds magic in the seediest of spots.

When I spoke with Atherton Lin just prior to Gay Bar’s publication, he was, like many people, under lockdown and missing his family in California, who he usually sees at least once a year. He was also fretting about how fun an online book launch could be.

The idea of a “gay bar” is strangely powerful. Even straight people who wouldn’t dream of going to one have a sense of what a gay bar is and how it fits into society. How did you decide to focus on gay bars as the story you wanted to tell?

It was something on people’s minds, specifically here in London, where, over the course of 10 years, half the bars had closed and there was a lot of media coverage about it: “It’s a shame that they’re closing, they’ve been safe spaces for queer people,” and so on. I wanted to figure out how I do or don’t relate to those spaces. A lot of the time, the places I thought were insignificant, disappointing, random or generic end up having really rich histories. One of the things a fissure like the pandemic throws into relief is the fact that the bars I took for granted when I was first going out were a very recent invention. They were slick, shiny—“chi-chi bars.” Those bars were very much a reaction to the AIDS epidemic and a repudiation of a sort of soiled identity. That’s an important discovery: That sometimes the history of a place is longer than you think, but also that the things you take for granted have a shorter history than you think. That’s important when you’re trying to figure out what was normal and how you’re going to return to it after the pandemic. You can’t necessarily take the status quo for granted.

So many stories about the decline of gay bars or gay villages have focused on market forces taking our institutions away from us, like the disappearance of blacksmiths or video-rental shops. You avoid that kind of trend-spotting. But ultimately, do you think gay bars are becoming obsolete?

I don’t subscribe to the idea that there is a first gay bar, or a “Gay Bar Common Era” or a gay bar grand narrative. So if they’ve been all sorts of things—certain kinds of pubs that have been taken over, cabarets that happened to have a queer clientele—if this variety of spaces counts, then the gay bar of the future, post-pandemic, will probably be a surprise too. In London before the lockdown, there really was a movement of young people making spaces for themselves, travelling space rather than established bars. But those established bars serve a purpose that gets ignored. The mediocre gay bar is a place to go after work for queer people, or sometimes women of various sexual orientations, who feel safer in a place that’s forefronted as gay.

Is there a bar that was the starting point for the book?

The London Appreciate in London. I still have the sign for it in my home. It proved to me how one object can become tentacular, touching on all these different areas. In that bar, there’s violence, there’s racism, there are issues of masculinity and self-presentation.

Your book reminds us how special moments in gay bars can feel few and far between: We arrive too early in the evening, we visit after a bar has passed its heyday. But maybe just one time, we have a fantastic encounter, so we’ll go back to that place over and over again. Is it that elusive nature of the pleasure of gay bars that keep us coming back?

As I’ve gotten older I’m a bit more forgiving about that disappointment. It’s no longer disillusionment—I’m complicit in the ennui of an okay night. You’re always going out for the possibility.

“I’m complicit in the ennui of an okay night.”

The book functions as a catalogue of gay bars that have been important to you, and it made me think of the pleasure gay men of a certain age take in reminiscing about bars they’ve been to, conjuring the details of places that may not exist anymore.

Some of the early press about the book has referred to it as a cultural history or even used the word “definitive.” But I always felt I was trying to write in a minor key, and most of the bars I give attention to are ones that aren’t globally known. They’re ones that happen to be where I live. I did live on the same street as the Twin Peaks Tavern [in San Francisco’s Castro neighbourhood], which is an icon globally. But each bar I write about represents something different. So Twin Peaks represents a move toward visibility, and in that move toward visibility, how it perhaps sanitizes the image of gayness as anodyne, politically upbeat.

As you introduce us to the gay bars you’ve visited, you also explore your own sense of identity: Gay, queer, fag, daddy. Are these identities about a final destination or being different people along life’s journey?

It’s funny, my family calls me Jem sometimes, and my mom called me Jemmy the other day. I was like, “That’s an epithet for gay men, supposedly coming from King James I.” She was like, “I won’t ever call you that again.” I was like, “No, that’s totally great.” Then she was like, “Which label do you prefer?” And I said, “I do like ‘fag,’” which surprised her. I certainly don’t want to speak on behalf of anybody else, but for me it’s always tempting to embrace the most taboo. In the United States recently, it’s very inappropriate to use “homosexual” as a noun, so then you want to reclaim that because it has the word “sex” in it, despite its pathologized past. It has a forbidden attraction. For me, any label is always going to feel like a slight misfit, a bit inadequate, and because of that I feel quite open to playing with them.

You recount a funny anecdote from when you were a student, and were RuPaul’s personal assistant.

It was a bit of a fluke and I’ve been dining out on it ever since. RuPaul’s such a powerhouse now. I was studying theatre at UCLA. There was a master’s student who must have thought this gay boy would like to do an internship on this television pilot RuPaul was doing. I’ve been thinking lately that homosexuality can be a private thing, but gay identity is public-facing. So I didn’t want to omit the fact that there are incidents where you become part of popular culture, even though I might feel as a writer that I’m just an observer.

What effect do you think RuPaul’s Drag Race has had on mainstreaming drag and the culture of gay bars?

I don’t know. It could be a larger force, but it’s RuPaul’s drive and personality and talent and vision that made it to TV. It was the right time in terms of various liberations.

I find that younger LGBTQ2S+ people, compared to gay men of previous generations, are more averse to giving offence—they’re interested in creating spaces that are safe for everyone. But you discuss how risk is an important part of going out. Do you think something is lost when spaces feel overpoliced or people worry about getting caught out for saying the wrong thing?

For me, yes. For a night out where I’d like to push my boundaries, yes. But I have come towards a conclusion that there are populations and groups that feel more vulnerable than a male-presenting person. In order to create the sort of atmosphere where risk and eroticism can be alive, there needs to be a set of boundaries they establish to then release. For the gay male experience, you pull yourself into a backroom or a darkroom—that’s a very particular thing. I was definitely writing a book about gay bars, even though queer spaces come into it. They’re very different in a lot of ways. It’s not always completely logical to lump different populations together when their experiences are so different.

In the book you refer to your partner as “Famous,” referencing Leonard Cohen’s song “Famous Blue Raincoat.” How does Famous feel about being turned into a character?

He’s an artist, a publisher and a writer, and we’re very involved in each other’s work. We’ve been so close for so long that I think most issues of what he feels comfortable with are unspoken. Most social engagements and interactions are performative in some way. I’ve got to perform myself as a writer and narrator. He feels quite connected to that joyful friction between the idea of a real self and a public-facing self.

How do you feel about COVID-19 taking away the “going out” part of your life?

The adjustment was fine. Some people around my age probably felt like it was a forced retirement. I have a happy domestic life and a lot of time my idea of nightlife exists in the imagination—we have our own two-person themed parties or pretend we’re in Key West.

Was there a point in your relationship when you had to negotiate going out as a couple or alone, when you had to negotiate being sexual in semi-public situations?

We’re very much a team. It would be unusual for me to go without him. We fell into it easily, but like anybody who’s trying to navigate the parameters of their relationship, there are issues. As trusting as the relationship is, jealousy and envy are inevitable. We’d only be uncomfortable with somebody who made us feel uncomfortable. In the moment, though, you want to snatch your love away from the hands of the unworthy.

What bar did you regret leaving out?

Pfaff’s beer cellar in New York City is not a gay bar, per se, but it’s where Walt Whitman hung out. It has a fascinating history. Upstairs in that building is where the DJ David Mancuso threw The Loft parties, which inspired Andrew Holleran’s [1978 novel] Dancer from the Dance. But I don’t have an intimate relationship with New York City, and for me it was important that the gay bars in the book were part of environments where I knew the culture quite well. Circus Disco in Los Angeles is mentioned fleetingly, but it’s fascinating to me that César Chávez held labour union meetings there. I would love someone to write the history of Circus. I know I claimed the title Gay Bar, but I’d love for other writers to feel inspired to look at their own history.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out by Jeremy Atherton Lin is published by Little, Brown and Company.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra