In 1992 a high school kid from the village of Creignish, Nova Scotia got a phone call from New York City. Theatre director JoAnne Akalaitis wanted him to perform in an opera composed by Philip Glass. While on holiday in Cape Breton, Akalaitis had seen the dark-haired lad fiddling at a square dance. Now, for $1,000 US per week and free room and board, he would spend three months doing eight shows weekly for the glitterati of Manhattan.

On the threshold of a Broadway debut, Ashley MacIsaac hung up the phone to face his mom leaning on the stove, “with her arms crossed and a suspicious look in her eye.” New York was no place for an impressionable Catholic boy of 17. Mom and dad consulted priest, family and Ashley’s teachers. The consensus, narrowly, was that this was an opportunity he shouldn’t miss.

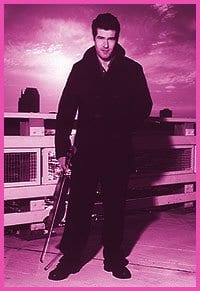

You can transport the boy to the Big Apple in a few hours, but how long does it take to pull up rural roots, or to purge a young mind of ingrained Catholic guilt? MacIsaac, the bad-boy fiddling dervish of Cape Breton, who introduced thousands of regular folks to the idea that water sports needn’t involve swimming or boating, is now pushing 30, with a career that shot skyward like a Roman candle, then flamed out with a bang. Somewhere underneath it all there still exists the breathless teenager on the phone to New York, and mom beside the stove in her apron, saying, “Not so fast.”

Mom was right. On his first evening in New York, Ashley left his Central Park West apartment, found his way to the subway and headed south. “I just picked a stop at random and went up to the street…. I was surrounded by peep shows and XXX movie shops and bums and porn. I couldn’t go 50 feet without someone offering me drugs or some hooker offering me sex. On top of that, there seemed to be black people everywhere, but not a white face in the crowd save for mine.” MacIsaac reports that he rose to the challenge. As he settled more and more into his gay skin, “accepting people who were different… became a sort of duty.”

Back home in Creignish after the show closed, he faced three months of catch-up schoolwork. The drudgery proved short-lived. On his second trip to New York MacIsaac met Paul Simon at a dinner with Philip Glass, and next morning he was in a recording studio with Simon and his wife, doing backup fiddle for her new record.

The high-powered connections launched a dizzying ascent to fame and a grueling tour schedule that took MacIsaac across North America and eventually to Europe, and even Japan, where true bliss was found in a Tokyo hotel bathroom: “I’m tellin’ ya, gettin’ music out of a toilet and water that squirts up and cleans your ass – that’s as good as it gets.” After selling 400,000 CDs and playing more than 1,000 gigs, he was barely 24, addicted to cocaine, and with about as much money in the bank “as I would have had if I’d had a paper route for that four or five years.”

One night he found himself alone in a Toronto hotel room at 3am with no cash or credit. Desperate for a hit of crack, he took his fiddle and the clock radio from the room and went down to his car. Cruising the drug corridor at Dundas and Sherbourne in his Olds, he tried to trade the radio and the fiddle for a fix. The dealers didn’t want the goods, so he went back to his hotel room and bawled his eyes out – not from “guilt because I’d tried to sell my fiddle. I cried because I couldn’t even get 25 bucks for my fiddle to buy some crack.”

We also learn that he’s HIV-negative, despite his estimate that half of his New York sex encounters in the early ’90s were unsafe. Through all of this soul-baring, MacIsaac’s voice (helped perhaps by his co-writer Francis Condron) retains a certain level of charm – until, that is, the infamous 1999 New Year’s Eve rave party in Halifax. We read that MacIsaac went onstage, played two or three notes, then began hurling sexual and racial abuse at the audience. “I even bent over a few times, it seems, and told the audience to suck my anus.” Naughty Ashley. The charm fades somewhat more as he admits singling out audience members with comments such as, “I’d like to cut your face off, faggot,” and “I’d like to take a knife and cut your uterus out, you dyke.”

A few pages later he complains that, “Canada is basically full of ignorant, hung-up, redneck homophobes and racists.” The unbridled candour in this book is unnerving. MacIsaac’s words reveal far more to the reader than he’s willing to acknowledge about himself. His own revelations seem lost on him.

* Ashley MacIsaac performs at the Canada Day celebrations on Tue, Jul 1 at Mel Lastman Square (5100 Yonge St).

FIDDLING WITH DISASTER.

Ashley MacIsaac.

Warwick Publishing. $18.99.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra