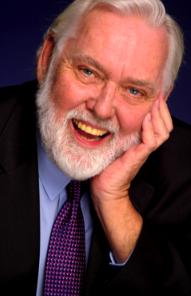

With family friends like Ethel Merman and Joan Crawford, it was sort of inevitable Jim Brochu would grow up to be either gay or in theatre. Being an ambitious individual, Brochu managed both.

“Well, originally I knew that I was born to be the first Brooklyn-born Pope,” Brochu says. “But my father had house seats for Gypsy and we went backstage. It was a religious experience for me. Ethel asked, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ At that moment the curtain went up and there I was on that stage with Ethel Merman, and I said, ‘I’m going to be a showgirl!’”

He was still a kid back then, but the brushes with greatness just kept coming. Brochu’s dad was a kind of accountant-to-the-stars, which afforded the youngster plenty of opportunities to ogle the glitterati up close and personal – though, perhaps not as personal as his randy daddy.

“In 1960 we were on a 30-day cruise to South America,” Brochu remembers. “Right down the hallway was Joan Crawford and her two children. My dad was a widower, she was widowed, and I was basically a matchmaker.”

What ensued was a deliciously torrid shipboard romance, with the elder Brochu and Baby Jane’s favourite sister going so far as to discuss commitment and marriage. But life in the limelight was anathema to Brochu’s reserved father, and they amicably parted ways.

Crawford and the young Brochu remained friends, and he is quick to set the record straight on the star’s less-than-maternal reputation as written by her daughter Christina in her book Mommie Dearest. “It seems part of my mission in life is to disabuse people of Christina’s story,” Brochu says. “It simply was not the Joan we all knew.”

Brochu’s past (or his autobiography, Watching from the Wings: An Offstage Look at Onstage Legends) reads like a subscription to Life magazine. His reminiscing about close friendships with stars like Lucille Ball (of whom he wrote in his book Afternoons with Lucy) could easily have kept him in dinner invites for a lifetime, but, as he told Merman, Brochu was determined to carve out a life onstage.

And he certainly has. Brochu’s resumé reads like the wish list of every stage, TV and film student looking for stardom. He’s appeared on everything from Cheers to All My Children, emoted onscreen with Robert De Niro and received raves in plays like Fiddler on the Roof and The Man Who Came to Dinner. But it is perhaps his self-penned plays that have been the most satisfying for the busy thespian.

His first big hit was Big Voice: God or Merman? a play he wrote with composer (and partner of 27 years) Steven Schalchlin. The autobiographical love story between Brochu and Schalchlin landed a ton of awards for the duo, while paying tribute to their shared musical idol.

Brochu’s early fraternization with the stars paid off yet again with his one-man play Zero Hour, a tribute to stage and screen actor Zero Mostel.

“Zero was playing Pseudolus at the Forum when I saw him,” Brochu says. “I was amazed by this force I was seeing onstage. Afterwards, I walked backstage and walked smack into Zero Mostel. I was wearing my military uniform and he looked at me and said, ‘Who are you, General Nuisance?’

“After that, all he would call me back then was Sergeant Brochu. I was hanging out a lot with him and saw how mercurial he was, and how talented. He would scare me sometimes but then sometimes make me laugh. He was truly unpredictable.”

Mostel was one of the many actors who saw their careers plummet after being hauled in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955 on charges of communism. He pleaded the Fifth Amendment, and his film and stage roles dried up overnight. Mostel retreated into isolation and painting for solace.

Brochu details these moments and more in his show, directed by Oscar-nominated actress Piper Laurie, completing a portrait every night as he regales audiences with stories of the comic actor’s wit and guile.

The show also affords Brochu a chance to indulge his painting, a passion he shared with Mostel. But creating a masterpiece both onstage and on-canvas each night has its challenges.

“In the beginning it’s really like rubbing your tummy and rubbing your head at the same time,” he says. “Sometimes early on I would get caught up in the painting. Then I’d be looking for colours and think, ‘Holy shit, what am I supposed to say now?’”

The Deets:

Zero Hour

Thurs, Feb 9 – Sun, March 11

Bathurst St Theatre

736 Bathurst St

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra