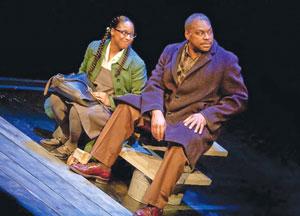

Starr Domingue (as Vonzia) and Jeremiah Sparks (as Lanier) in Oil and Water. Credit: Peter Bromley

Newfoundland is a place where stories have always played a role in governing the human condition. Certain stories are experienced, others passed down by elders — some affect us forever.

Robert Chafe, a gay Governor General’s Award–winning playwright, knows this, incorporating powerful stories into his work. When he first heard the tale of Lanier Phillips he knew he had to retell it.

Phillips was the only African-American survivor aboard the USS Truxtun, which ran aground off the coast of Newfoundland near the town of St Lawrence in 1942, along with a ship it was escorting, the USS Pollux.

Phillips was among 46 men rescued. Having grown up in the American South amid segregation, he was surprised when townspeople treated him kindly. One local, Violet Pike, was surprised when she could not scrub Phillips’ skin white — she thought his black skin was oil from the shipwreck that wouldn’t come off.

Pike nursed Phillips back to health in her home. He was so touched by this treatment he later donated money to the community so that a playground could be built.

Chafe says something in the tale called out to him.

Oil and Water is the result. The story of Phillips’ life and an homage to the island, it blends an a cappella score of Newfoundland folk music and African-American gospel.

“The play is this father grappling with this memory at this moment of crisis in his daughter’s life,” Chafe says. “He’s grappling with this trauma from early in his life and sharing it with her to save her the way St Lawrence saved him.”

Chafe dedicated the play, which will be released in book form by Playwrights Canada Press later this spring, to his grandmother.

“There was something about Violet Pike and the seclusion and isolation that bred an innocence,” Chafe says. “When I heard about the mistake, I thought of my grandmother — she would have been that person.”

For Phillips, it was the first time in his life he was treated as an equal by white people — he was offered tea in china cups, dined with the family, and slept in a bed. Those few days in Newfoundland forever changed the way he saw the world. He returned to St Lawrence in February for the 70th anniversary of the disaster. He died soon after, on March 12, just days shy of his 89th birthday.

“I’m very sad. I guess that’s an understatement; I’ve been pretty messed up for a few days,” says Chafe, who had met Phillips and spent two and a half years researching his life.

“I fell in love with his story a long time ago; he was this kind of mythic person to me. I remember the first time I called him on the phone . . . I was shaking.”

Chafe pauses, tears welling in his eyes.

“There is this almost false connection you establish as a subject,” he says. “I realized yesterday that what I am really upset about is he was just really good. He was a really good person. The more I look around at the world, it could use more people like him.”

Chafe recently relocated to Toronto from St John’s to pursue a fine arts master’s degree in creative writing.

His previous works, Butler’s Marsh and Tempting Providence, were nominated for Governor General’s Awards. He won the award in 2010 for Afterimage, a play based on Michael Crummey’s short story of the same name.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra