I’m having tea with Terry Haines, who shares a cozy East Vancouver bungalow with his partner Aaron. “Do you have a cat?” I ask him, intuitively assuming that one would leap up onto my lap from beneath the couch.

“No, Aaron’s allergic to them. The only cats I have are up over there,” he replies, motioning to a small shelf on the wall containing about two dozen small, porcelain cats, their nine lives frozen in time like tiny porcelain deities.

On another shelf sits a row of old wind-up alarm clocks. Haines stands on a chair, reaches up and takes them down to show me one by one. Their faces are caked in dust. They’ve been up there for a long time, as decorations, not timepieces. As soon as he puts them back up they start ticking again. The clocks simultaneously awake.

“It doesn’t take much to get them going,” says Haines.

Haines is a gay aboriginal artist living with HIV. His film Painted Positive is an intensely personal view into his thoughts, feelings and experiences.

Like the clocks on his shelf, Haines’ life is characterized by an ironclad routine. Unlike the clocks, which can be restarted or neglected at will, his HIV cannot be ignored.

“I think there’s still a sense of stigma attached to the disease and now it’s even morphing into something else,” says Haines. “People seem to have an idea that HIV and AIDS is manageable, which in a sense it is, but it’s still not going away and it’s still not a cure. People are still dying from it.”

The film opens with images of Haines entwined in red and green ribbon running down the length of his arms, binding his hands and covering his eyes. The subtle, graceful movement of his arms and torso amid the strands of ribbon create the illusion of a dance piece, although Haines says this was an unanticipated result.

“We didn’t realize it would come out as dance footage but I’m glad it did,” he says. “We just wanted the sense of being entwined in red ribbon, entwined in this disease. Your feet are bound because you have it, right? There’s no getting around it. You just live with it.”

His soft, deep voice provides the framework for his message of education-and alarm. Much of his monologue is a close-up of his face looking directly into the camera.

“It makes you have to look and have to listen to what I’m saying. In my mind, when I was making it, that was the way I would connect to the audience: to directly look them right in the eye,” says Haines.

During his six-month training course in digital video and television at the Native Education Centre, his instructors told him that you aren’t supposed to look directly into the camera, so he decided to do the exact opposite. “That’s how I am,” he says emphatically. “You tell me not to do something and I’ll do it. Just to be different.”

At the start of the movie, Haines lists the three strikes he sees ranged against him: being aboriginal, gay and HIV-positive.

“From my perspective it’s a strike against me because I’m First Nations but I’m non-status First Nations, which means somewhere down the line my family lost their right to native status,” he explains. “My mom recently got it back, but none of my brothers or myself can get it because of the way the government has categorized who is and who isn’t. I applied three times for my status over the years and have been refused each time. So it’s like, ‘Okay, I’ll give up on that.'”

He recalls hitting a particularly rough patch at one point and turning to some social service agencies for support. Under the impression that they would help people with HIV who were experiencing financial difficulties, he asked them for a subsidized bus pass to get out and look for work, but was denied. For Haines, the experience added another layer of humiliation to an already painful situation.

“First of all, it’s almost degrading to ask people for help,” he says, “and then to get turned down is a double. So I just thought I’m going to look for work and do what I can and deal with it. Accept my situation and try and work and at least be self-sufficient in that way. So that’s what I do, I work all the time.”

By sharing his story Haines hopes to educate people.

“I wonder if they’ll ever find a cure. I wonder if they’ll find a cure in my time,” he says in his video. “Let’s educate ourselves. Might be too late for me; it’s not too late for some of you. We need to treat this disease as serious as it is. It’s taking lives all the time.”

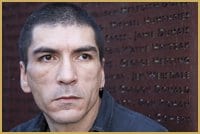

Some of these lives are honoured on the Vancouver AIDS Memorial located at Sunset Beach, which figures prominently in Painted Positive. “One of my old bosses had fought to get the wall put there, Ed Lee, and I wanted to honour him and his fight for that wall in the movie,” says Haines.

In the film, Haines places himself against the backdrop of the wall. Above him are the many names of those who have passed and below him blank space. “The last shot was me sitting halfway between the names and the blank. It’s kind of an unsaid message that I could be on that wall.”

Haines believes the wall should go around the entire park, not just sit in one section. “It’s important to pay attention to the people who have passed, living with it and fighting to get awareness,” he says. “It’s still there, it’s still happening. It’s not just a one-day-of-the-year event; it’s all year long.

“People shouldn’t be afraid to say I’m HIV-positive,” he continues. “People aren’t afraid to say, ‘I have cancer.’ In my eyes it’s almost the same thing.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra