Soulpepper theatre is conducting a master class in modern theatre history this summer. Samuel Beckett’s classic Waiting For Godot opened in June and will be returning in August. In the meantime, two plays that would probably not exist without Beckett’s example are being produced as a double bill at the Harbourfront Theatre Centre.

The Dumb Waiter and The Zoo Story are two plays written in the decade after Godot appeared, written by two authors profoundly affected by the revolution in theatre that it ushered in.

The Dumb Waiter was written in 1957 by English playwright Harold Pinter. The Zoo Story was written in 1959 by American playwright Edward Albee. There are superficial similarities between the two plays, apart from the dates of their writing and their homage to Beckett. Both are one-act works involving a continuing dialogue between two men. In both, the characters’ conversations reflect their attitudes toward their social class, make obvious their relative successes and failures, illustrate the nervous contempt toward women that underlies so much maleness and continually hints at the violent nature of society. An eruption of that underlying violence is the culmination of both plays.

By pairing them together, Albert Schultz, the artistic director of Soulpepper, has produced a fascinating comparison study of the early work of two great authors, and has incidentally illustrated how both employ their knowledge of the hidden lives of gay men to write plays about sexually indeterminate and morally confused relationships.

Harold Pinter began his career as a straight young actor in the notoriously gay English repertory theatre world of the 1950s. He soon became aware of the conflict between the underlying nature of that world and the essentially dishonest face that many of its participants had to show in public. He knew that the men around him were in regular danger of imprisonment and blackmail because of the laws against any male-to-male sexual acts. That awareness blended with his own identity as a Jewish child growing up in the 1930s in London’s East End at a time of openly anti-Semitic violence. What has followed is a body of work which always features his characters’ ability to hide their nature or desires behind a barrage of verbal indirection and threatening hostility. His plays continually explore the homoerotic lies that permeate the lives of ostensibly straight men. So in The Dumb Waiter two working-class hit men are in a decrepit basement together waiting to be informed about their next victim.

Edward Albee is a gay man who fled a life of upper-class rigidity in the ’50s by escaping to the welcoming bohemian arms of New York’s Greenwich Village. His plays, like Pinter’s, are full of characters who explore the confusions of class distinction and the role- playing involved in all kinds of relationships. The Zoo Story is an early example, featuring a character of a peculiarly indeterminate sexuality reaching out to a comfortable middle-class family man one afternoon in Central Park – and the chaos that follows.

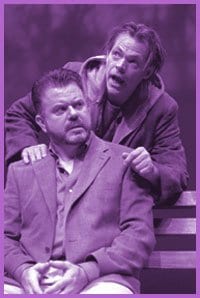

Stuart Hughes and Michael Hanrahan play the two characters in each of the plays in the double bill, a casting move that allows the audience a full appreciation of the similarities and differences of the styles of the playwrights. In each case Hughes plays the character who is the instigator of the action, while Hanrahan’s characters seem, on the surface only, to be solidly passive observers pulled into action in spite of themselves.

Starting with Pinter’s hilarious, single-minded viciousness and following up with a particularly fine reading of Albee’s characters’ overpowering wordiness, the two actors perform a triumphantly successful acting lesson. Hughes and Hanrahan use body language and speech patterns to inhabit completely different men in each play.

Director Ted Dykstra has kept a tight rein on the pacing and movement of both veteran actors. Pinter’s famous pauses are timed perfectly, not exaggerated for effect as many nervous directors do. With Dykstra’s directorial assistance, Hanrahan is able to retain the audience’s interest while managing to avoid upstaging his partner as Hughes delivers what is essentially a monologue in The Zoo Story.

Between them, the three have made this Soulpepper production a must-see event this summer.

* The Dumb Waiter and The Zoo Story play together Monday through Saturday at 8pm, with 2pm matinees on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Tickets for evening performances range from $36 to $49, with matinee shows selling for $30 or $25 for students with ID. Shows are at Harbourfront Centre Theatre (231 Queens Quay W); the box office is at 235 Queens Quay W. Call (416) 973-4000 for more info.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra