This story is part of our Rainbow Rewind 2019 series—looking back at the past year and decade in politics, health, culture and more.

RuPaul’s Drag Race is the quintessential TV show of the 2010s (sure, the drag-and-drama series premiered in 2009, but I would never criticize a queen for being early).

The show came about as the reality TV boom waned, and remained strong until the genre came back into fashion. It celebrated queerness at a time when the representation of LGBTQ communities was increasingly in demand. It even encapsulated some of the difficult conversations we had this decade, discussing issues of race, trans rights and more (although it didn’t always handle them well). But most notably, Drag Race catapulted drag itself into the stratosphere, making the art form popular and profitable on a scale never seen before.

In many ways, this is something to celebrate—a massively expanded revenue stream for LGBTQ people that didn’t exist in this form before the show. It has also opened drag up beyond its underground roots in a way that, for some, comes at the cost of authenticity. RuPaul spent so many years saying drag will never be mainstream that we never stopped to ask ourselves: What would it mean if it did? When it happened, it brought about a new age of prosperity for drag queens but completely transformed drag’s audience to the point where it isn’t exclusively for queer people anymore.

Mainstreaming drag has shown how there are numerous ways to be a successful drag queen. Before Drag Race became a phenomenon, there were relatively few ways to make it big in drag. Willam, Season 4’s resident bad girl, was one of the most famous among the early alumni, and even her résumé at the time was mostly filled with bit parts on TV. That should put it into perspective: An IMDb page with one-episode TV stints was a major success for a drag queen not named RuPaul or Lady Bunny.

In the late-aughts, queens were mostly known locally. While social media existed, there was no reliable way for them to grow their fan base beyond their local communities. Visiting other cities for gigs did happen, but full-blown tours didn’t have the core base to sustain themselves. Local success wasn’t a bad thing, but it was tough to grow beyond that in a pre-Drag Race world.

Season 2 fan favourite Pandora Boxx was one of the first queens to really build a fanbase online, garnering, what at the time, was a huge number of fans on her Facebook page. For years Pandora was second only to Ru herself in terms of online popularity, though she’s not as popular now. When Drag Race grew in size and scope, gaining a new, glossier sheen around Season 4 or 5 (all the while keeping the grit that defined the first three seasons), Pandora Boxx’s level of popularity was no longer unique. Contestants like Sharon Needles, Latrice Royale, Alaska and Alyssa Edwards’ fandoms have transcended the popularity they had during their original seasons. The queens’ growing clout led to brand expansions and tours, with marquee shows like Battle of the Seasons becoming big hits. (The Werq the World Tour, heading into its newest incarnation next year, is the modern equivalent of these shows.)

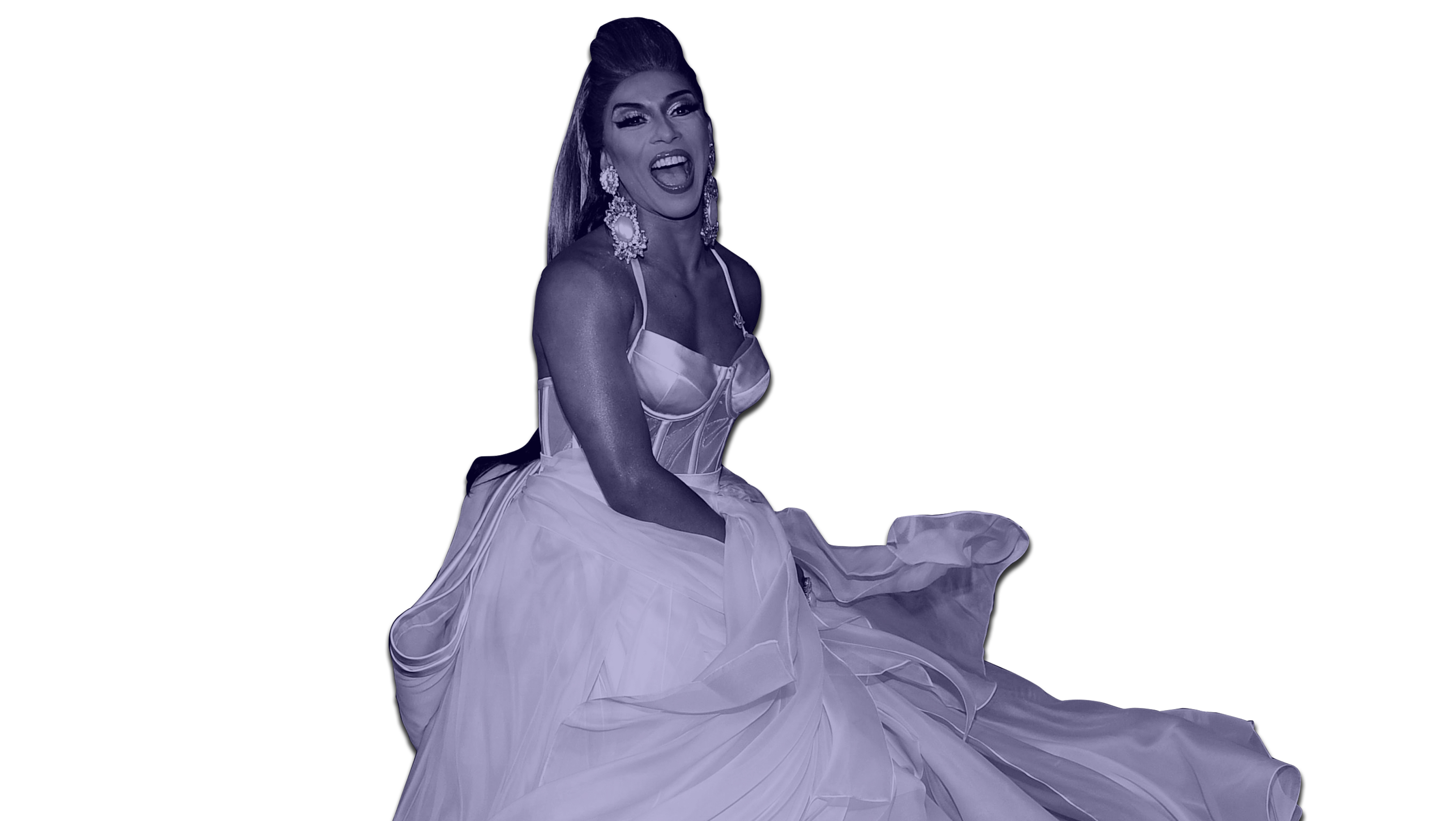

Nowadays, queens who succeed on the show routinely gain massive audiences on social media—at the time this article was written, more than two dozen of them had a million or more Instagram followers. (Season 6 champion Bianca Del Rio actually has more than two million.) Beyond the Werq the World Tour, queens regularly travel on their own to visit fans, and some create tours of their own: Season 7’s Kennedy Davenport took her house on the road earlier this year, while Season 5 champion Jinkx Monsoon and Season 6’s Miss Congeniality, BenDeLaCreme, are currently on a Christmas tour together.

Going on the road is not the only way queens performed drag and expanded their brands. YouTube has become one of the biggest homes for queens looking for their next project. Alyssa Edwards’ Alyssa’s Secret and Season 7 compatriots Katya and Trixie Mattel’s UNHhhh became massive hits, the latter even inspiring a short-lived expansion series on Viceland called The Trixie & Katya Show. The format has been beneficial for Drag Race production company World of Wonder, too, as they host many of the shows on their YouTube channel (they now also have a streaming service, WOW Presents Plus).

Following in Ru’s footsteps, several queens have released their own music after appearing on Drag Race. Trixie’s country-folk music has proven particularly popular, while more traditional dance and rap tracks are a staple of any winning queen’s post-Drag Race career. Season 5’s Alaska and Season 6’s Adore Delano have both released multiple albums, with the latter effectively becoming a drag rock star.

There are limits to all this, though, particularly in terms of who gets to be successful. Most of the queens who enjoy the largest fan bases are white or white-presenting; Season 8 winner Bob the Drag Queen, Season 8 and All Stars 4 runner-up Naomi Smalls and multi-season stalwart Shangela are the only Black queens from Drag Race in the one million club on Instagram. Most of the biggest web series are hosted and centred around white or white-presenting queens. There are a few different reasons for this, including in the production of Drag Race itself, but one that’s undeniable is an audience that, since around Season 7 (although there were indications of it before then), has overwhelmingly preferred white, thin, pretty queens.

In recent years, and especially since the show’s move from LGBTQ cable network Logo to the broader audience of VH1, the fanbase has gotten much younger, with teen girls occupying a significant space within the fandom. In some ways, this change hasn’t affected the queens much. Trixie Mattel, who enjoys one of the youngest fan bases among all Drag Race alumni, has said she doesn’t edit her act based on the age of who’s in her audience. But Drag Race itself has morphed to fit its new audience, becoming less queer and more family-friendly. In an interview on NPR’s It’s Been a Minute, World of Wonder’s ringleaders Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey expressed pride in this change in Drag Race’s audience. For them, the mainstreaming of drag is a feature, not a bug. The show must change to fit that.

That change has also come with a major brand expansion: There are typically two seasons of Drag Race broadcast on VH1 every year, a regular variant and an All Stars season. Additionally, the show has launched international versions in Chile, Thailand, the United Kingdom and, soon enough, Canada. (An Australian version was also announced, although there’s been minimal news since.) This makes the franchise akin to other reality empires like The Amazing Race, Top Model and Big Brother.

To many, this is an unabashedly good thing: It took far too long for Drag Race to be recognized as the behemoth that it is. That the show only earned its first Emmy for Best Reality-Competition Series for its tenth season is absurd. Season 10 was hardly the best Drag Race had to offer, and it deserved at minimum just nominations, not wins. Golden-era seasons like Season 2, Season 5 and Season 6 were much more deserving of that accolade.

Growing Drag Race’s brand is a great way for the show to be properly recognized as a legendary part of the reality TV pantheon. But some have argued that its expansion dilutes its brand, overwhelming fans with droves of content. It’s become a trope that any announcement of new content—from the casting of an upcoming season to a celebrity spin-off—will be met by fans bemoaning that they feel smothered by too much Drag Race. (Most still watch, however, which is likely why the flow has not stopped.)

Perhaps the best example of just how transformative the past decade has been for both drag and Drag Race is in the number of contestants who became drag queens because of the show. These are young queer men who were inspired by the show, and then went on the show to inspire others. Season 8 winner Bob the Drag Queen proudly confessed to this in his pre-season Meet the Queens video, and Drag Race UK’s Blu Hydrangea called herself “Generation Ru” in the series premiere. Outside of Drag Race, a lot of young people were also influenced by the show, as seen in documentaries like Drag Kids wherein young people explore the world of drag with the support of their families. This phenomenon has become either an inspiring cycle or an ouroboros; your opinion on that is likely influenced by your opinion on the mainstreaming of drag as a whole.

To be blunt, there will likely never be a consensus on this topic: For everyone who argues that drag moving out of the underground into the spotlight is great for LGBTQ artists, others will argue it drains drag of its genuine charms. The same goes for Drag Race’s expansion itself, as those who want more will forever be at odds with those who think there’s too much. Drag Race is too big to inspire the same thoughts in all who watch it, and it has likely changed drag irreversibly.

If I had to put together a wish list for Drag Race in the 2020s—beyond the fact that I want it to survive to the end of the next decade—I’d first ask for more opportunities for the queens themselves. RuPaul featuring 22 of the show’s alumni on her new Netflix series AJ and the Queen is a huge step in the right direction. I’d love to see more queens in major feature films, like Shangela and Willam in last year’s A Star Is Born. I’d also like to see further opportunities for the queens to be part of expanding the brand, akin to Season 11’s Brooke Lynn Hytes judging Canada’s Drag Race. Because, at the end of the day, my deepest desire is for the queens of Drag Race to benefit from the show’s expansion. RuPaul and the producers are successful several dozens of times over; the series’ alumni, who make tuning-in week after week and season after a season worth it, deserve their coin—and not just the whitest and prettiest among them.

The past decade was a transformative time for drag. All we can hope for now is that, rather than be a temporary trend, the form stays around as a thriving artistic and business opportunity for queer people. We hope it shantays.

This story is part of our Rainbow Rewind 2019 series—looking back at the past year and decade in politics, health, culture and more.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra