Desmond Child has been talking to you for a long time. Maybe you haven’t realized.

For the past 40 years, Desmond Child has been the trailblazing collaborator and magician behind your favourite songs by Christina Aguilera, KISS, Michael Bolton, Bon Jovi, Ricky Martin, Sisqó, Cher and many others. But his story is so much more than who he’s worked with.

Child’s lengthy career spans multiple eras, composed of a discography with over 1,600 credits. He earned a Grammy Award in 2000 and the ASCAP Founders Award in 2018; was nominated for an Emmy Award in 2003; was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2008 and has had more than 80 singles top the Billboard charts. “I think there was one week when there were five of my songs in the Top 20,” he tells me from his office in Nashville, Tennessee, where he now resides.

Though he helped to pen several of the world renowned hits in the ’80s and early ’90s that made bands like Bon Jovi and KISS household names, executives began to limit his opportunities to produce for and work with the industry’s top entertainers. In record label offices, Child’s abilities were overshadowed by the stigma that came with him being one of the few out gay men in music. “This was years before Elton John even came out, or George Michael and all of that,” he remembers. “Everyone was still playing it really safe…I felt intimidated and ashamed.”

Despite his meteoritic success as a songwriter at the time, Child struggled to navigate industry politics, and the effect it had on him was “painful.” While he doesn’t explicitly say it, it’s not a stretch to assume Child’s sexuality may have prevented him—and many of music’s most prominent artists at the time—from being offered opportunities of a lifetime.

While 66-year-old Child loves to talk about the quintessential, chaotic American life he’s had, don’t mistake that for nostalgia; he’s far from living in the past.

His journeyman’s retelling of events makes it clear that he defines himself by who—and how—he helps people. That’s the entire reason he decided to become a musician: “Being born to immigrants, being poor and being gay, there were lots of things I had to overcome in trying to figure out a way that I can do something in life so that I can take care of my mother,” he says. “And, you know, I figured it out.”

It all started with his mother, Cuban-born songwriter Elena Casals. “She would work all day somewhere, and then go out at night to nightclubs with her [guitar] case and lyric sheets and try to get artists to [record her demo],” Child says.

Born John Charles Barrett, he grew up in Miami in the late ’50s and ’60s. Child remembers when “relatives started arriving” to live with them in Liberty City after the Cuban Revolution.

“I grew up in the projects, you know, surrounded by my Cuban family who had fled in the exile community.” He refers to the Barry Jenkins film Moonlight to describe the setting of where he lived. “Those were the projects that I grew up in. That was the exact layout of where I lived. The whole thing.”

Child credits all of his hustle and skills to Casals. “My mother was an artist—a true artist. She was writing from the pit of her soul, and that’s how I know to do it,” he says. “That’s why I think I’ve been successful and survived so many genres. It’s about that, telling the story and expressing one’s self.”

His mother’s influence at home, combined with the rock n’ roll that took the world by storm in the ’60s, meant that Child spent his teen years going to concerts featuring Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell and Laura Nyro. It was where his passion for music flourished.

He used his aunt’s address to enroll at Miami Beach Senior High School, which produced several successful alumni—particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. It was where most children from prominent families attended. Child joyfully recalls that his protector from the bullies was Mickey Rourke. “And a couple of years before me was Andy García,” Child says. “We all came from humble beginnings as well, and so the poor kids kind of hung together.”

But Child’s time there wasn’t as glamorous as it may sound—it was his upper-class peers who enjoyed the luxuries of the time: “There were the very wealthy kids whose parents… were involved in building or running the big hotels on Miami Beach,” he recalls. “Kids we knew lived in mansions on North Bay Road that had boats and docks in the back and all of that.”

Child found something different. “There was always a little clique of the outcasts, the people who later figured out they were gay… those were the people I gravitated towards.” In that clique, Child met his first writing partner, Debbie Wall, and they formed the duo Nightchild. Wall changed her name to Virgil Night, and “I became Desmond Child—Desmond for the Beatles song, ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’.”

The androgyny of the “Desmond” in the Paul McCartney-written song (“Has a barrow in the market-place,” “Stays at home and does his pretty face”) was part of the name’s appeal for Child. “At those times, people were androgynous, [and] I didn’t know what gay was, really. I just felt. I had girlfriends and boyfriends. To me, that was what ‘being a rock star’ is.”

After high school, Child’s ambition took him to New York City, where he met his girlfriend and eventual bandmate, Maria Vidal. While he studied at New York University, Vidal was working as a waitress and using the name Gina Velvet—an important fact because, as he often tells, it led to the character in the story of “Livin’ On A Prayer” by Bon Jovi, a song co-written in collaboration with Child. “She’s the real Gina.”

In the ’70s, Child and Vidal, together with Myriam Valle and Diana Grasselli, made up the band Desmond Child & Rouge, which enjoyed early success as having a “coming out of New York, cabaret feel” band. Their song, “Last of an Ancient Breed,” made it onto The Warriors soundtrack in 1979, and they had a few Billboard-listed releases. “I mean, we got to do Saturday Night Live as the guest musical stars,” Child says. “We did stuff, we toured the country and had a hit.”

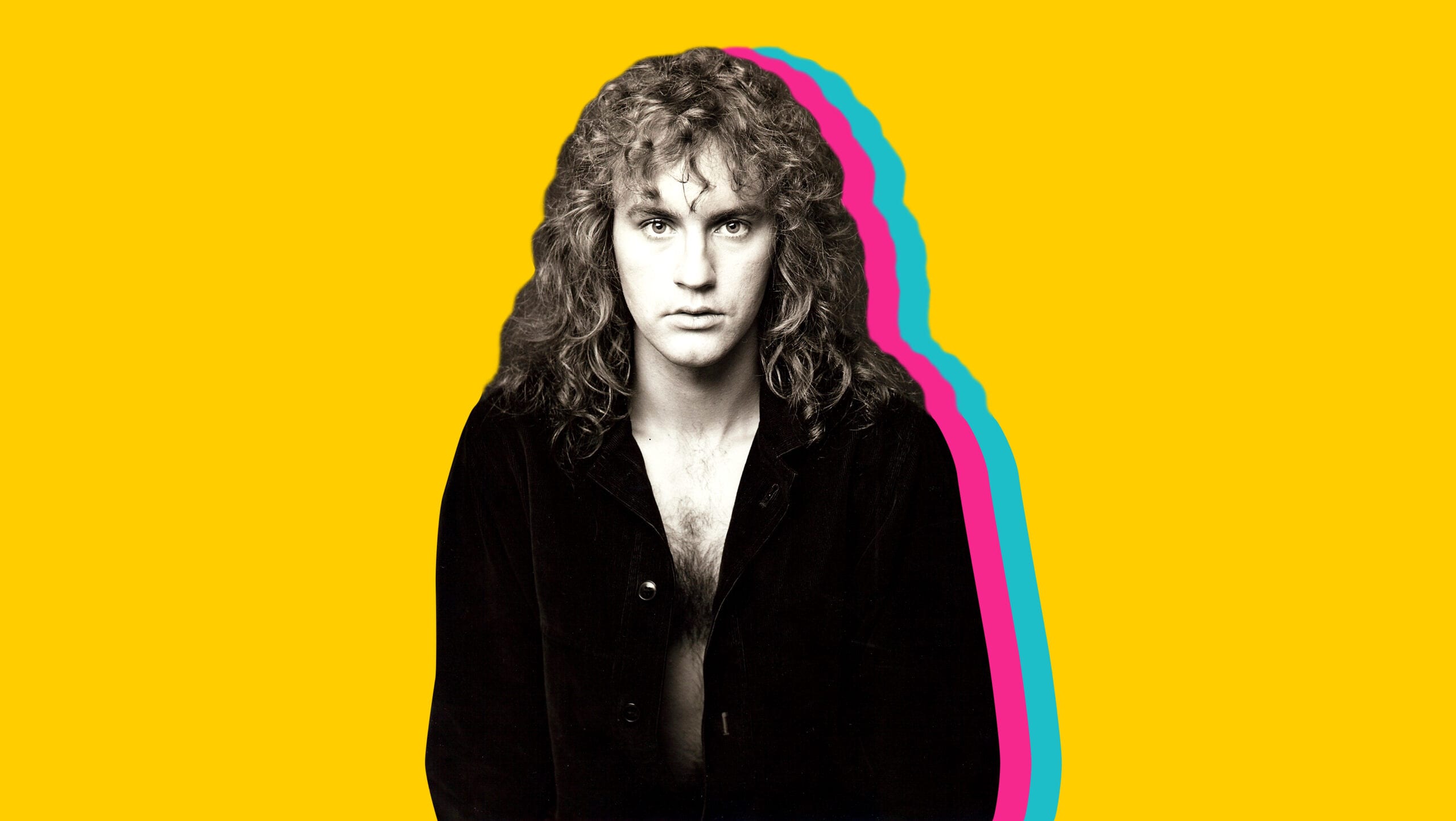

That hit was “Our Love is Insane,” which got the attention of KISS guitarist/vocalist Paul Stanley. Stanley and Child then wrote the worldwide hit “I Was Made for Lovin’ You” together, launching the start of Child’s songwriting career.

Entering the ’80s, Child’s role as the lead member of Desmond Child & Rouge—and as Vidal’s muse—faded. “After making our first album, I started to realize that I was more gay than bi, and me and Maria separated.

Desmond Child & Rouge Credit: Courtesy Desmond Child

“The thing is, Desmond Child & Rouge was so special, and it really was a special time,” Child says. “Living in New York, we were brushing shoulders with Andy Warhol, or we’d be in Reno Sweeney’s and Jacqueline Onassis would walk by with Henry and Nancy Kissinger… This was before AIDS came and darkened our world.”

In addition to the drug epidemic, several of Child’s New York friends succumbed to AIDS. “That period was so alive and so fun, and then of course, AIDS happened—and almost everyone we knew was dying,” Child strains to say. Later, that included his brother, Joey, who passed in 1991. “But the survivors—we’re still very tight. We love each other like brothers and sisters.”

As a songwriter, Child began crafting anthems with different rock stars—Aerosmith, Cher, Joan Jett—but he was limited by people in the industry. “For decades,” he says, “I was the only out gay producer in the music industry. The only one, in any genre.”

Between executives and A&Rs, most record labels didn’t want to hire a gay man as a producer. From Child’s perspective, this is due to the “boy’s club” nature of the industry at the time.

“When I finally came out, then it was like, ‘nobody wants you because you’re gay,’” Child recalls. “For someone from my world, the most gay part of the business was the dance remixers, as that became more popular. They would be performing at the gay clubs and all that kind of stuff. For the nuts and bolts of rock and other kinds of music at labels, it was all controlled by straight people. There really was a glass ceiling.

“The thing is that bands were fine co-writing with me, but they didn’t want to be dick slapped in the studio by a gay dude,” Child says. “Because, the truth is, the producer—in the end—is the boss.”

As the number of hits Child contributed to increased, he managed to receive more writing and producing opportunities—albeit, with “the androgynous weirdos” of the time, like Alice Cooper and Ronnie Spector. And he was able to record and issue his solo debut, Discipline, in 1991, which he described as “feeling like I had to go back into the closet to do it.”

Soon, industry shifts—like the ousting of Elektra Records executive Bob Krasnow, the first A&R to sign Child—meant opportunities became limited again. Whispers and bigoted remarks from within the industry where passed on to Child though friends like fellow songwriter Diane Warren. “I would, y’know, hear that certain A&R guys [would say], ‘Oh, that guy doesn’t really like you ’cause you’re gay,’ and they would call me the ‘F’ word,” Child says.

Though he found his way from genre to genre—executive producing for metal band Ratt and glam guitarist Kane Roberts, and later co-writing “Weird” for boy band Hanson in 1998—Child wasn’t producing the kind of music he knew he could. “I wasn’t getting to produce the rock bands or in the genre that I was really, really good at.”

In 1989, Child met voice actor and musician Curtis Shaw, who he describes as “one of the warmest, most wonderful people ever.” At the time, Curtis was a maître d’ at a NYC restaurant. The two hit it off, and started a 32-year long relationship. “I’ve been lucky to have a partner that loves me so much,” he says in a euphoric tone.

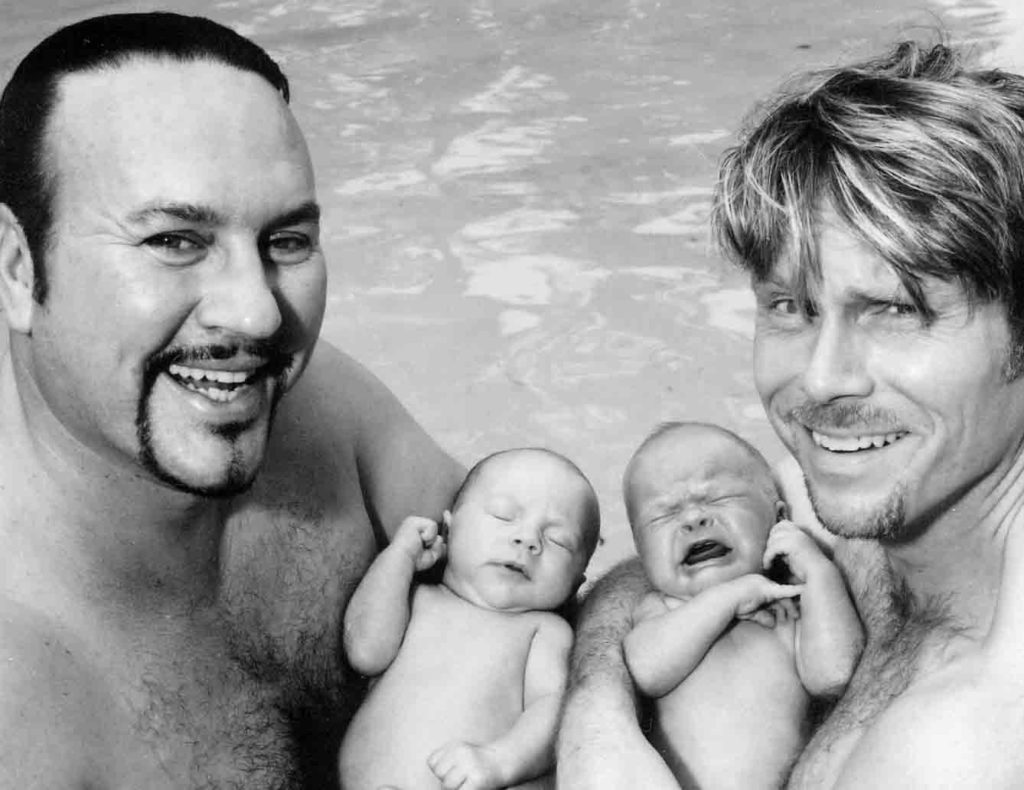

Curtis Shaw, Desmond Child, and their two sons. Credit: Courtesy Desmond Child

But while Child now had a life partner and good relationships with fellow entertainers and outcasts he considered family, he wanted more. He embarked on a journey that would turn out to be his most defiant accomplishment: Becoming a father.

Child’s path to fatherhood with Curtis was chronicled in the documentary, Two: The Story of Roman & Nyro (2013)—partly narrated by the twin sons the couple would eventually have. The film chronicles their decade-long journey to have a child via surrogate, and their life after their children’s birth. (They met their surrogate, Angela Whittaker, through mutual spiritual circles in India with Deepak Chopra.)

Child still takes pride in the way they proved naysayers (such as former President George W. Bush) wrong, and showed everyone that gay men can raise children—even their own. “We’re not sterile! We’re not shooting blanks!” he proclaims. “We can have children. Our own, bio-log-ic-al children.”

Child describes his sons’ birth, which was made possible through in vitro fertilization, as “a huge turning point.” They worked with the Growing Generations surrogacy agency and their sons, Roman and Nyro, were the 60th birth facilitated by the organization. “Now there’s hundreds of thousands of people that were born that way, to gay men as parents,” Child says.

The couple “got very uncomfortable in the state of Florida” after their son’s birth, however, because the state didn’t allow a second parent adoption by a gay spouse. So, they “sold everything” and relocated to California to marry in 2008, just prior to the passage of Proposition 8—a ballot which eliminated the right of same-sex couples to marry. (In 2013, Prop 8 was found to be unconstitutional and LGBTQ2 couples’ right to marriage was reinstated in California. Marriage equality was legalized across all of the United States in 2015.)

Even now, nothing gets Child more excited than discussing his sons, who just turned 18. He describes them now as “the biggest jocks in the world,” despite taking them to see “every Broadway show since they were two years old.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_8XOKphVP0/

“‘How are they so straight? What the heck happened? How did I fail?’” he wonders, jokingly. “I guess that’s how straight people feel when their children are gay, right?”

Child’s songwriting career continued as he raised his children. He met Ricky Martin and they put together the hit “Livin’ La Vida Loca” in 1999, which changed the entire landscape of Latin music. “It was a sensation, that was the millennium song from hell,” Child remembers. “At that time, everyone wanted to be a Latin lover or… date a Latin lover, let’s put it that way.”

Then came opportunities to produce for rock bands like The Scorpions and The Rasmus. He kept working with familiar collaborators in Alice Cooper, Meat Loaf and Bon Jovi, while also crafting memorable songs for Disney and American Idol alums of the 2000s, in addition to co-writing Katy Perry’s “Waking Up in Vegas.”

In between, the Child family moved to Nashville, where Child and Shaw decided they could give their sons “a healthier, safer life.” Child was now tasked with finding time to join his husband and kids at soccer meets, which exposed them to people who had never met a gay family—or, even, out LGBTQ2 people. “Curtis, he’d just win over the moms. So, I’d do my best to talk to the dads and all of that. And together, we won them over…all of a sudden, we weren’t scary. Plus, our sons were the strong players on the field.”

Desmond Child performing live. Credit: Courtesy Desmond Child

There’s plenty of rock star-equivalent stories that Child is ready to share, such as unintentionally introducing Cher to Bon Jovi guitarist Richie Sambora (“and the rest is tabloid history”). He also says he recently shared with boy band Hanson that the song he wrote with them, “Weird,” was actually about being gay. Apparently, one of the brothers then told lead vocalist Taylor: “So that’s why everyone thinks you’re gay.”

Now Child is focusing on himself again. Desmond Child Live (Deston/BMG), released several months ago, is Child’s first live album, and his second LP in 30 years.

While it’s filled with live performances of hits Child has either written or contributed to, along with other songs that have meant a lot to him—the other Rouge members even join him for some performances—it actually serves as a glimpse into the musician’s future. He wants to tell his story, and he knows exactly how to get people to listen: His upcoming autobiography, Desmond Child Livin’ On a Prayer: Big Songs, Big Life, written with David Ritz, will be accompanied by a documentary—and people have already contacted him about movie rights, he says.

Child hopes his own story will be received the way retellings of the lives of other gay musicians in the industry have been. He’s also pushing on with bringing a Broadway show, Cuba Libre, to the stage. Written in collaboration with Davitt Sigerson, it tells the true story of Child’s two aunts “who became the ‘it’ girls in Havana—two dictators, one island. You do the math.”

Child is not looking toward anything that suggests an end to his career. He expresses, with disappointment, that “the value of songs really were decimated by the way digital and streaming was set up, from the beginning.” But he’s still sharing his talent for storytelling. He implores us to listen to his latest collaboration, the song “Lady Liberty” with Barbra Streisand that was released as a single in late 2018. He expresses his desire to work with Ryan Tedder, Halsey and Sia, while also noting that he’s got a duet with Alice Cooper planned for release this year. He tells me how he loves out pop stars Troye Sivan and Sam Smith because “they don’t give a fuck.”

He suggests to any aspiring LGBTQ2 musicians that—besides living as themselves proudly—they move to music towns like New York City and Los Angeles and start networking. In Canada, he points to Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal as music centres, too.

“It was very lonely for me for decades, and I’m very happy that we’re finally getting more,” Child says. “Let’s not take it for granted, because there are folks that are trying to turn the clock back.”

Even after 40 years of recording music in a business where evanescence is common and talent doesn’t always shine, Child remains a strong storyteller and an anamorphic rock star—and now a family man, too. Most important of all, he’s still “trying to be a good dad, trying to be home for dinner.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra