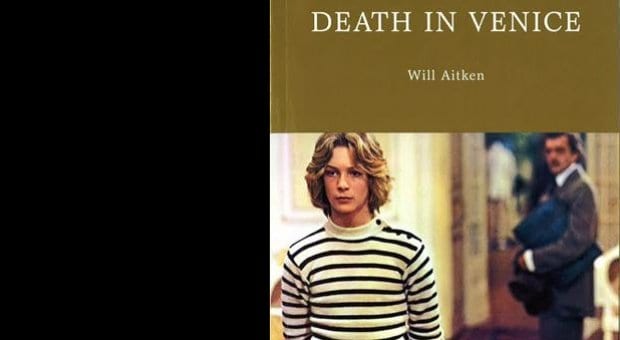

Legendary Italian director Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film Death in Venice marks yet another inspired edition of Arsenal Pulp Press’s Queer Film Classics series, which examines some of the most pivotal films about and by lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people. The series is co-edited by author Thomas Waugh and Xtra contributor Matthew Hays. Nine of a planned 21 monographs have so far been released, each written by a different leading film scholar or critic. The Venice monograph was assigned to Will Aitken, a Montreal-based novelist, journalist, screenwriter, multimedia director and teacher.

Based on Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella of the same name, Death in Venice follows a middle-aged, generally heterosexual German author (Dirk Bogarde) who is vacationing alone in Venice. He becomes obsessed with an adolescent boy (Björn Andrésen) who is staying at the same hotel. As the fixation intensifies, the film makes explicit what Mann’s novella kept implicit: an aesthetically intense depiction of unconsummated, pederastic love.

Over 168 pages, Aitken’s contribution to Queer Film Classics delves into all aspects of the film, including its fascinating external narrative. Warner Brothers put up two thirds of the budget for this arty Italian film about a middle-aged man’s obsession with a pubescent boy – a ridiculous fantasy scenario these days. Moreover, and despite mixed and often homophobic reviews, the film became a huge box-office success, the biggest of Visconti’s career.

Aitken spends a good third of the monograph on Visconti himself. He writes on how he grew up in a family headed by one of Milan’s most preeminent couples in grand residence “with so many windows there were servants specifically assigned to the task of opening and closing them”; how his mascara-wearing father had extra-marital affairs with members of both sexes; and – most extensively – how Visconti handled his own homosexuality, which was an open secret but one Visconti never actually spoke a word about.

It’s an engrossing biography that Aitken handles with care, covering well beyond the basics in the tight page count. He also opens with it, which gives the reader a great primer on Visconti’s background and psychology before taking on Aitken’s rigorous analysis of the film itself – a film that continues to stand as one of the most compelling works of one of cinema’s most compelling filmmakers. But while many writers have taken the story on before, it’s nice to have Aitken and Queer Film Classics give it such an officially queer look.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra