Warning: This review contains a discussion of child sexual abuse.

“This book is about how I was taught to read and how I was taught to fuck,” Steacy Easton writes in the prologue to their new book, Daddy Lessons—a tempting description for all the horny queer theory nerds out there. Such succinctness sets the tone for this exercise in memoir, literary analysis and pornography. Easton picks apart the erotic threads of their life, through a series of “daddy lessons,” the titles of which alternate between gay porn parody (“The Farmer Teaches the City Kid How to Be a Boy,” “Looking for a Daddy in All the Right Places,” “Cowboy Takes Me Away”) and academic paper (“On the Sanctification of Violence,” “Text Becomes Flesh”). Easton is concerned with the meeting of sex and text: in these lessons, learning “how to hold a cock” and “how to parse a sentence” are equally important pedagogies. Daddy Lessons is concerned with desire and how it plays out in the world, with making desire overt and palpable, including the reality of children’s desire—and the ways in which this can be exploited by adults.

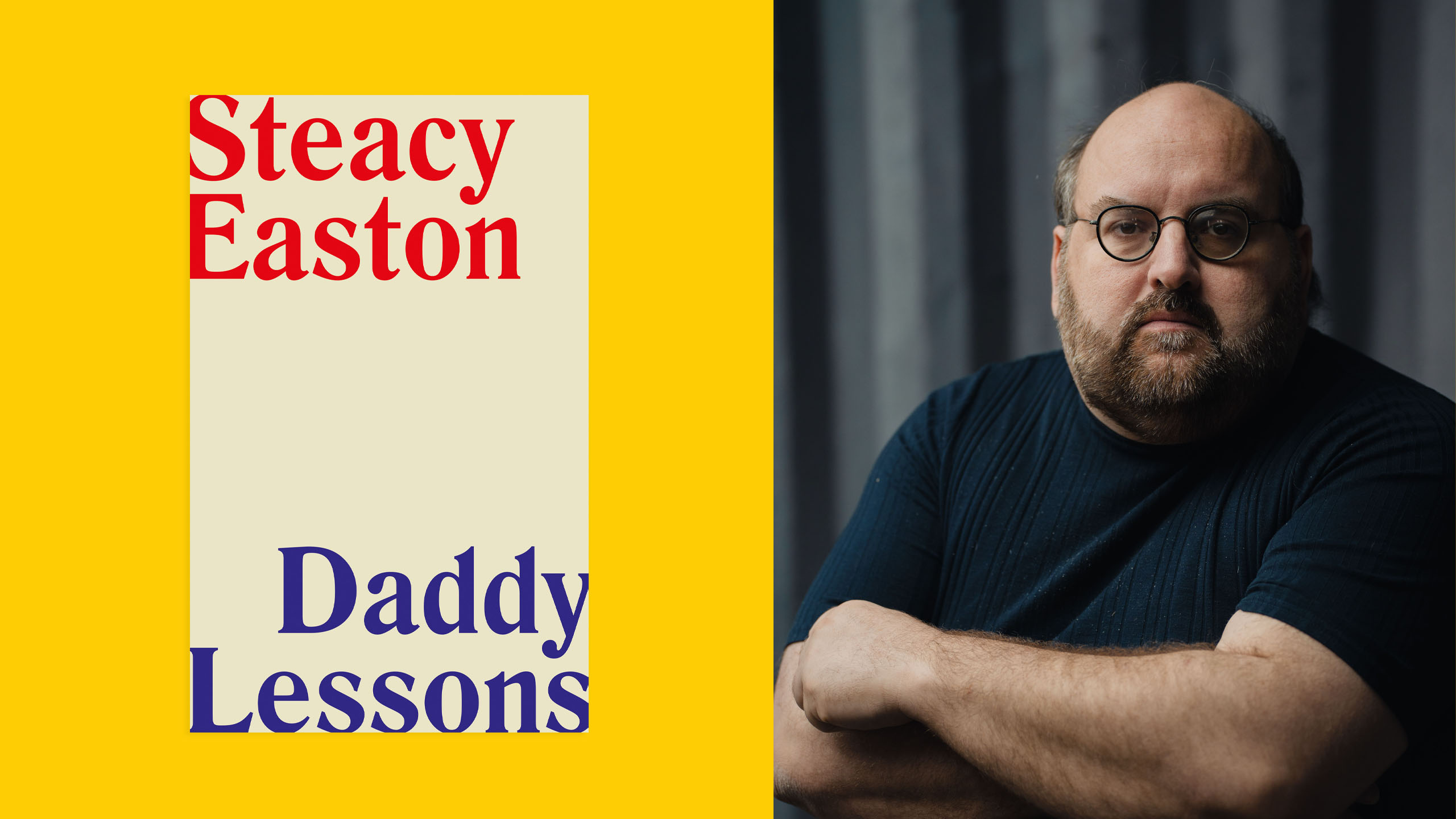

Easton is a critic, academic and artist, who grew up in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, and currently lives in Hamilton, Ontario. Daddy Lessons is Easton’s second book, which comes fast on the heels of their first book, Why Tammy Wynette Matters, also published this year. In this newest book, Easton writes into a rich legacy of memoirs that contend with the far-reaching influence of religion on queer and trans lives. Daniel Allen Cox’s I Felt the End Before It Came, published earlier this year, dissects the author’s upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness and his subsequent long process of leaving the religion and living a queer life; We Have Always Been Here by Samra Habib explores the complexities of Habib’s queer Muslim identity; Boy Erased, Garrard Conley’s 2017 memoir, traces Conley’s forced conversion therapy by his Baptist family; an old favourite of mine is Kate Bornstein’s A Queer and Pleasant Danger, the self-professed gender outlaw’s memoir of their stint as an inner-circle Scientologist in the 1970s, before they came out as trans.

Daddy Lessons is, like many queer and trans memoirs, a non-linear, hybrid text: it is memoir and it is also a series of short essays, each one (except one interlude) a daddy lesson taken from Easton’s life. It is also pornography—certain sections are rife with the sensory details of sexual encounters, including those that occur in Easton’s imagination. “Pornography teaches,” they write. “It is a genre of formal experimentation: the same limited bodies in the same infinite variations. In queer spaces, it also allows for the possibilities of those bodies in ways that religious or other moral teachings limit.”

That Daddy Lessons can’t be easily placed in one genre mimics the complex weave of Easton’s own life: raised in more than one religion; being a queer child and then young adult who also continued to attend religious gatherings that did not welcome queerness, which was deemed “undeniably toxic.” In one lesson, they describe a typical week during their twenties: “Youth group with the Mormons on Tuesday; church work with the Catholics on Thursday; gay social group on Friday.” Easton was raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints, in Alberta. They were sent to Anglican boarding school for grades 7 and 8, and then in Grade 9, had a yearlong stint in an adolescent psychiatric facility. In high school, they began frequenting the gay bathhouses and adult theatres of Edmonton. These institutions all had their own forms of etiquette, Easton writes—and they studiously learned them all. They point out the parallel between collecting converts to the Mormon church, and queer cruising in public space: “The tension between picking up and being picked up was central to learning how to be a good Mormon, and eventually how to be effective at queer sex.”

There is a tension in Daddy Lessons between personal anecdotes and Easton’s analysis of those experiences. Sometimes the balance is well struck; at other times, Easton tends a little too heavily toward theorizing their life, without giving the reader much contextual or experiential information. In one lesson, they describe a Neil LaBute play in somewhat confusing terms, jumping between scenes in a way that might only be understood by those who are already familiar with it. I kept waiting for Easton to show up in this lesson, which focuses on Mormon men and homosociality/homophobia, but they never really appear. In another lesson, they describe working for an Anglican priest at a school in Montreal, as well as a theological thesis they wrote about a 17th-century devotional poet, and a series of sexual assaults that happened in several Canadian private schools in the 1970s to the mid-1990s. The various beats of this chapter are difficult to follow—Easton jumps between personal moments, historical records and the subjects of their own research in a manner that is more jarring than cohesive. Lessons like these ones, which analyze texts and artworks that Easton connects to their own life experiences, but in which they barely appear in the flesh, read like separate critical essays, interrupting the flow of the more memoir-oriented lessons.

In their prologue, describing the book’s intentions, Easton name-checks the original collection of dirty stories: “a post-gender, post-sexuality Prairie Faggot Decameron.” I found myself wishing at certain points that the stories leaned further into Decameron-esque bawdy storytelling, and away from the instinct to theorize what the desire and the sex might mean. Easton is a strong prose writer and is amply able to convey complexity, longing and eroticism in-scene. When they do allow themself to slow down, to linger in the materials of their memory a little longer, the reader is more able to fully enter each recollected moment, rather than being rushed to theorize the moments before they can land.

The lessons in which Easton brings us deeper into the experience they are discussing are the most effective and affecting. In “Lesson Four: Restriction and Expansion in Missionary Territories among Missionary Bodies,” they write about how, when they were 18, the Mormon church elders were so concerned about what Easton describes as their “feral” nature, that two slightly older missionaries were assigned to guide them. Easton names the seductive undertones of this set-up: the idea is that the adolescent Easton will be seduced back into the church through the social attention of these older boys. They are invited to the missionaries’ apartment for a birthday meal: “the blandest meal, with the blandest men, and I’ve never felt more special.” Instead, while one of the boys leaves the apartment to get groceries, Easton and the other hook up: Easton gives him a blowjob, the missionary still in his Mormon underwear—a sacred garment given to and worn by adherents after they turn 18. Of course, the other missionary returns in the middle of this scene, spilling a carton of milk all over the floor—a pornographic finish. “I never get the underwear,” Easton writes at the end of the lesson. “I get a lifetime of wanting instead.”

Later in life, they fantasize about fucking the missionary in the suburban home he now shares with his wife and kids. There is a wistfulness here, as well as queer rebellion: this desire to disrupt church-approved heteronormative structures via queer sex (which many church-involved men, including one of Easton’s teachers, are very happy to partake in), layered with the loneliness that can come with existing outside of normative societal structures, even the ones that we don’t want to be part of.

Easton is at their most incisive when they write about the ambivalent relationship they had with the teacher who sexually abused them at boarding school. The teacher, whom they refer to as “the Dorm Master,” tells Easton “I needed discipline, that I was a bad kid, that I caused my parents heartbreak, that I didn’t know how to be a man, and that he would make me a man.” Easton is in Grade 7 at this point, and already aware that their father “was a fuck-up, unable to parent.” They sought out various replacements for their inadequate father—thus the daddy lessons, and this teacher was one of them. They write about his sexual abuse of them, and also about their own very real queer desire at that age. “The Dorm Master saw what I wanted and he gave it to me,” they write.

Throughout the book, Easton is dedicated to naming the fact of desire in children, which goes against the idea that, as Easton writes in “Lesson Twelve: Text Becomes Flesh,” “sexuality is delivered by cherubim via satin pillow the minute you turn 18.” This idea, they say, enables homophobes and transphobes to assert that queer or trans children are fictions. And yet, of course, despite Easton’s desire, they were a 12-year-old student at the time, and “had no say in how the Dorm Master touched my body and usurped my desires.” There is a way to recognize children’s sexuality as an adult, without exploiting it, writes Easton. “The hunger that the child has for adult things beyond their understanding must be noted and must be put away.” Much later, at 40 years old, they testified against the Dorm Master in court. Even then, they write of their ambivalence—they recognize that the Dorm Master behaved in ways that he should not have, that his actions were exploitative of Easton’s own queer desire as a child and, at the same time, seeing him in court, they still “want him to love [them].”

Daddy Lessons is a somewhat overly theoretical text for one so interested in desire, sex, sexuality, bodily wants and excretions. I wanted Easton’s language to inhabit the body more, and the emotions surrounding the various experiences of sex, gender-fuckery and ferality. When they do this, in chapters that spend more time in various desire eras from their life, like the lesson in which they fuck a rodeo cowboy in various motels throughout Alberta, wondering if he loves them, or the one in which they describe various experiences in Edmonton’s video booths and porn theatres, à la Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, the book sings with queer lust, with the overlay of joy and melancholia that these encounters (or encounters wished for and just out of reach) can elicit. Often though, the book slides into an abstracted state, similar to what Easton describes in the chapter about their courtroom appearance: the more the lawyers talked about sex, “the more and more abstracted the idea of bodies became.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra