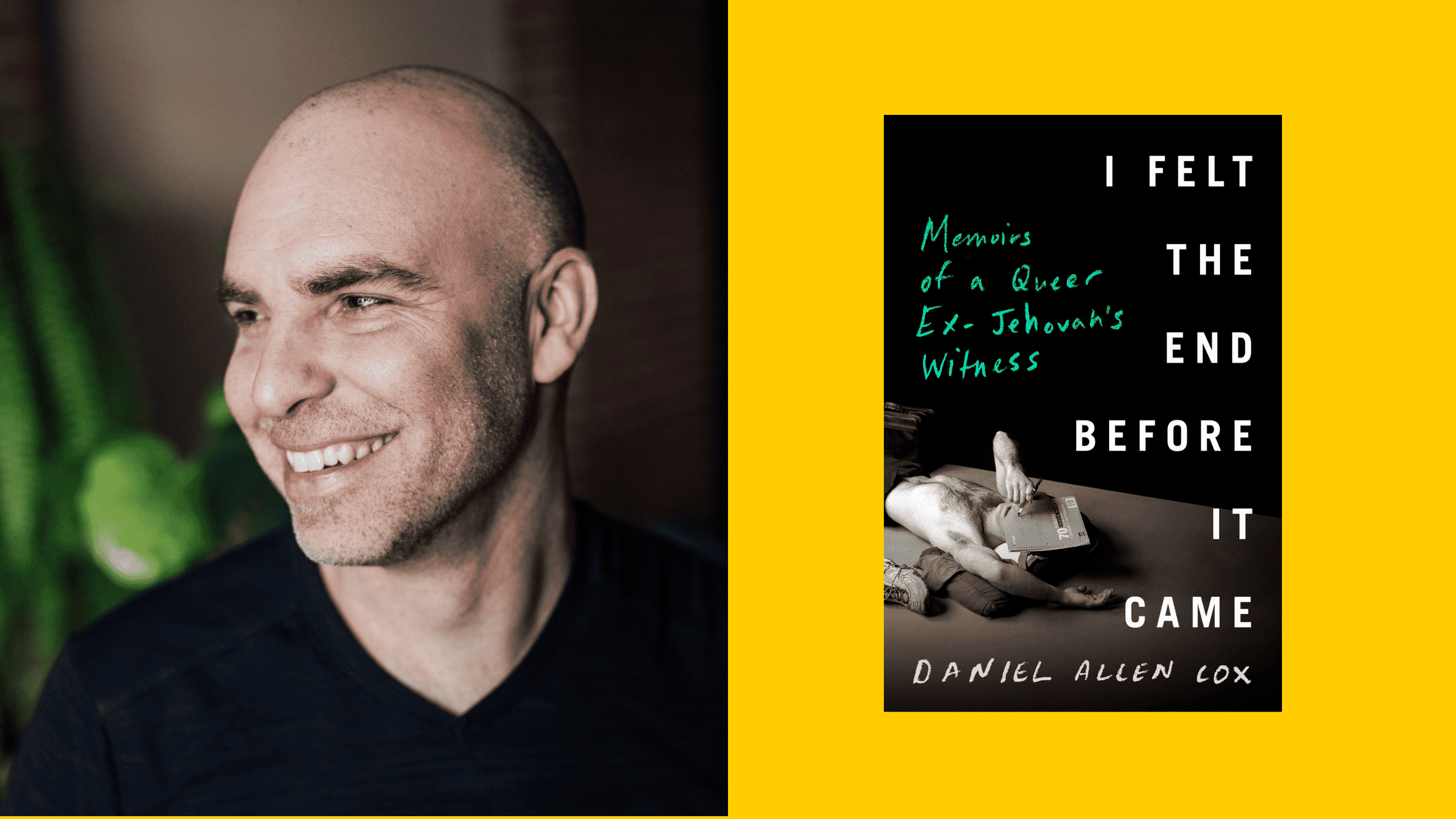

“It is where words fail that language truly begins,” Daniel Allen Cox writes in I Felt the End Before It Came: Memoirs of a Queer Ex-Jehovah’s Witness, his first memoir. Here he examines his upbringing in the cult-like Jehovah’s Witnesses, his queer coming of age in Montreal and New York City and his development as a writer. Cox’s struggle to find the right language illuminates the text and shifts the emotional terrain—from growing up as a stutterer to negotiating addiction to modelling for porn and searching for a “theology of queer tenderness.”

Cox is the author of four novels that mine the minutiae of gay life, from a hustler taking refuge in the Fiorucci storeroom in late-’90s New York (Shuck) to pyromaniacs playing parkour and fighting homophobia in Krakow, Poland (Krakow Melt). With I Felt the End Before It Came, Cox moves his eye for meticulous atmospheric detail to his own life, opening up a refreshing vulnerability. If Cox is “a memoirist who wishes to forget,” as he wonders in the book, he delivers the details to the world so that we will remember.

I spoke with Cox about his lifelong struggle to deal with the impact of growing up in the Jehovah’s Witnesses, how language can be used as a weapon and a means of survival, self-actualization in writing and in life and letting desire lead the way.

You grew up in the suburbs of Montreal in the intensely homophobic Jehovah’s Witnesses, and went door to door with them as a teenager in the late ’80s and early ’90s to preach the gospel of Armageddon. When you were outed at age 18, you sent a breakup letter to the Witnesses that you describe as “a horniness for a future that made sense.” I wonder if you could talk about the connections here between desire and self-actualization.

The Witnesses are all about suppressing desires, on the basis that desires can only get us into trouble, and I was like, “what if I wanted a life of trouble?” I was taught to distrust my feelings—we couldn’t possibly know what was good for us because only the hierarchy of the cult could decide that. But desires don’t go away that easily. And because my critical thinking skills had been blunted for so long, I had to let desires lead the way. So, when I put my body on a bus out of the suburbs and paid the fare for it, then put that body on a dancefloor downtown so the beat could shake it, then watched that body go home with someone who found a home inside that body until it all happened again, verily I say unto you, dear Mattilda, that my de-indoctrination had begun.

As for that de-indoctrination, you write that “one cannot imagine escape, or agency, or the true shape of one’s life until there is a language for it.”

It was toxic to be in a group that delegitimizes queer life in every way, using language as its main weapon. Mostly, it’s an absence. The word queer doesn’t appear in any Witness publications except to mean strange. Trans and non-binary people don’t exist in the JW universe. It’s hard to understate how tightly the language was controlled. In Watch Tower Society books and magazines, we read the questions under the text, highlighted the answers and recited them aloud at the meetings verbatim, with almost no leeway to insert words of our own. Under these conditions, how could I discover queer and imagine a future inside it? I had to find a way outside that restricted lexicon.

Like many teenagers, you were in an alternative rock band—music was essential to your survival, but in the book, you look back at your songs as cheesy posturing, although one lyric stands out to you: “Sometimes the only way to know is to feel.” It strikes me that this is a central theme throughout the book, would you agree?

Yes, I would. At different times in my life, I’ve had to react to situations before being able to articulate the details. Sometimes I find the words much later, and by then, they’re made from the material of a life, and stronger for it. My favorite books are built on self-knowledge as an accrual of feeling, which makes the language a vivid, bubbling, unruly thing. I enjoy nothing more than watching a writer work out arguments on the page in real time, drawing from half-admitted, nebulous feelings about things. Maybe this is a way to write memoir that accesses real experiences, not just as a catalogue of the past, but as an inventory of our ever-unfolding present. Do you know what I mean?

Yes. One example is how you mention your stepfather’s abuse almost casually, and yet you are clear about its impact—at times you still worry that he is right behind you, and about to smack you in the head. “Pain doesn’t lessen when you confront it,” you write, and I wonder if you could talk about what happens instead.

We writers agree to a trade-off that’s not necessarily good for us: we get to shape trauma how we want, but once we invite it back inside the house, we don’t get to say when it leaves. When I access trauma, it insists on living in my present, replaying on a loop. It usually overstays its welcome. There is no mastering trauma, only peeling back its layers, which can be painful in infinitely new ways. There can be healing, of course, although it’s problematic to focus on catharsis alone at the expense of everything else. T Kira Madden has written about crafting something until there’s room for more than catharsis, like space for readers’ own experiences.

You struggle as an adult with the legacy of your indoctrination in the Jehovah’s Witnesses. In the book, you wonder “if [you] can ever hear music without feeling religious” and asking yourself if there’s a way to describe the actual apocalypse of the climate crisis without the religious language of a fake apocalypse. Do you think this skepticism enhances your power of observation?

I think I’ve gotten good at spotting religious fervour in different contexts. I know when I’m backsliding to Christian narratives in my tweets or in my writing, but if I can do something fun and subversive with it, I don’t always mind. I try to stay aware of ways I haven’t fully unchained language from how it was once used to regulate my thinking, but there’s still so much influence I can’t see. When I was working on the manuscript of I Felt the End Before It Came with my editor, David, he asked me what I meant by the word witness, which I was using as a verb. I was trying to say preach, not observe, and had no clue. So when I hear jargon, I try to break it down to the elemental, which leads to writing. Rather than hemming in lexicons, why not open them up? I think often about how you once said that “language is a search for more language.” Do you remember saying that?

Yes, I can sense that search here in your book too. It’s funny that we both lived in New York in the late ’90s, but we didn’t meet until several years after we’d both left. Most of I Felt the End Before It Came takes place in or near Montreal, where you grew up, but there are flashes of New York throughout, especially at the end, when you talk about living there at the height of the Giuliani years, with its crackdown on public sex and queer visibility. How did this time form you?

New York is where I learned that the strongest way a community can come together to accomplish something is through hybridity. I fell in with a bunch of ne’er-do-wells and witnessed this first-hand in their response and resistance to Giuliani’s reign, among other things. I learned how activism and artmaking could swirl together to bridge art forms and scenes where there’s no standard set of methods or aesthetics. Endless permutations where you can mix work and play and pleasure and advocacy to achieve an effect. I can see the influence of this in almost everything I do.

Near the end of the book, you mention a porn shoot for Honcho magazine—you appear on the cover in army fatigues, wrapped in the U.S. flag, like some ironic symbol of blood-drenched U.S. patriotism, but what you’re disturbed about is that they airbrushed out your pubic hair. I’m struck by the humour throughout the book. No matter how serious something is, there’s always a sense of play in the language or the way you tell the story. How did you maintain this?

Oh god, that magazine cover. I’ll be spending the rest of my life trying to figure out why I let the stylist dress me up like a military assassin at the same time as I was otherwise doing everything I could to protest the effects of law enforcement on the city.

I was mostly unaware of the humour in this book while I was writing it. People would read excerpts and ask me about the jokes. What jokes? I only really noticed the humour when I was narrating my audiobook and sometimes had to stop mid-sentence to laugh with the director and the sound engineer. I could tell you something like I subconsciously used humour as a palliative to the trauma I was writing through, but that would just be a cliché. What’s more accurate is that so many elements of growing up a Jehovah’s Witness are so surreal as to be farcical, and there’s no way to reconcile with the contradictions of that kind of upbringing without laughing at it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra