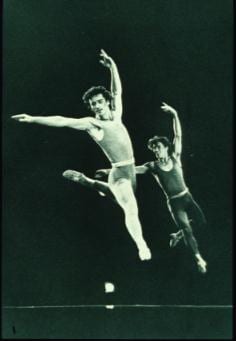

Dancers in Arpino's Trinity.

When choreographer Robert Joffrey died, he left behind one of the great ballet companies in American history. Founded in 1954 with partner Gerald Arpino, the Joffrey Ballet revolutionized not only what dance could look like, but also its function in society, a process detailed in Bob Hercules’ new documentary Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance.

“In some ways, it was the first truly American dance company,” Hercules says. “They left behind much of the European tradition other companies were following, incorporating pop culture, rock music and psychedelic projections. More importantly, they explored contemporary political issues, something dance had been essentially forbidden to do.”

Composed of archival footage, mixed with interviews with former company members and associates, the film paints a portrait of a creative duo who changed their art form by ignoring all the rules. But while they went against the grain professionally, when it came to their personal life, convention ruled, at least in outward appearances.

Though Joffrey and Arpino met and fell in love in 1945 when they were still teenagers, moving from Seattle to New York together to pursue their dream of starting a dance company, their relationship was largely on the down-low. They would refer to each other as cousins publicly, though it was widely known they were more than that.

“It never really became clear in making the film why they weren’t more open, since everyone around them probably knew,” Hercules says. “But there was still a lot of stigma attached to being gay, even in a place like New York.”

Though not a large part of their public persona, sexuality was a definite feature in their work. Pieces like 1966’s Olympics (a nearly nude tribute to the original Greek sports spectacular) and 1967’s Asarte (an orgiastic multimedia acid trip of seduction) placed lust front and centre. Their audiences were often surprisingly young, attracting the same people to ballet who would be going to Pink Floyd and Jefferson Airplane shows. Not interested in classical stories, Joffrey and Arpino considered themselves current-events choreographers and created work about the time they were living in.

As in life, Joffrey fought to keep details surrounding his death a secret. When diagnosed with AIDS in 1987, his company spokesman explained his visibly weakened state as a resurgence of his childhood asthma. A year later, his obituary gave “liver, renal and respiratory failure” as his cause of death. Arpino then took the reins alone and ran the company until 2008. They’d terminated their sexual relationship years earlier, despite continuing to live together.

Though not the first high-profile artist to die of AIDS, or even the first in his own company (several of his dancers had previously succumbed), Joffrey’s insistence on keeping his illness secret may have been an attempt to protect his art form.

“It was suggested he thought his diagnosis might reflect poorly on his company,” Hercules says. “Even though he wanted to break artistic boundaries, he felt a ballet company needed to maintain a certain propriety, and he didn’t want AIDS associated with his artistic legacy.”

The deets:

Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance

Opens Fri,Oct 5

ByTowne Cinema

325 Rideau St.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra