Berlin provides a relentlessly bleak, ominous backdrop to the conflicted lives of its Muslim residents in Burhan Qurbani’s Shahada, a film that takes its title from the Islamic declaration of faith.

It’s one thing to quote the declaration with apparent authority: that there is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet. Quite another to know with authority what Allah — if Allah exists — means or wants. But that doesn’t stop Qurbani’s protagonists from trying to convince themselves and others that they do.

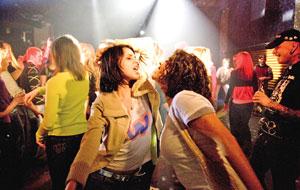

A seemingly carefree, street-smart Maryam, the daughter of an imam, parties with frenzied abandon. “Only sleeping, drinking, breathing, fucking is what I must do,” she parrots lustily in unison with her friend Renan and fellow nightclubbers. But a secret abortion, and the subsequent hemorrhaging that just won’t stop, send Maryam spiralling into hallucinatory guilt and an increasingly fundamentalist interpretation of what Allah wants and what the Koran means.

Senegalese factory worker Sammi does his best to be a good son and Muslim. Except that Sammi’s in love with coworker Daniel — and surrenders to his desire — leaving him in the torturous grip of a shame that he violently, but regretfully, acts out on his lover.

“Just say it once . . . that you liked it, too,” Daniel repeatedly begs of him.

“My faith forbids it,” Sammi replies.

Invested with such omniscient power and desire to seek vengeance, God remains Shahada’s invisible character. But in a decidedly stereotype-purged turn, imam Vedat is the voice of reason, a stand-in for the silent Allah.

“We’ve got enough fundamentalists in the community,” Vedat tells his increasingly austere daughter, who confuses rote repetition of Koranic passages with wisdom. “Stop quoting,” he implores her. “You’re talking like an old man.”

“In the eyes of Allah, all forms of love are good,” he offers a shame-ridden Sammi.

But Vedat’s pleas are drowning in what he sees as a tide of deeply entrenched, misguided beliefs that weigh and prey on the city’s Muslim community.

There are no easy fixes or resolutions to the increasingly universal, secular-versus-sectarian quandaries in which Maryam and Sammi are immersed. To his credit, Qurbani judiciously leaves his characters to find their own ways — or not.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra