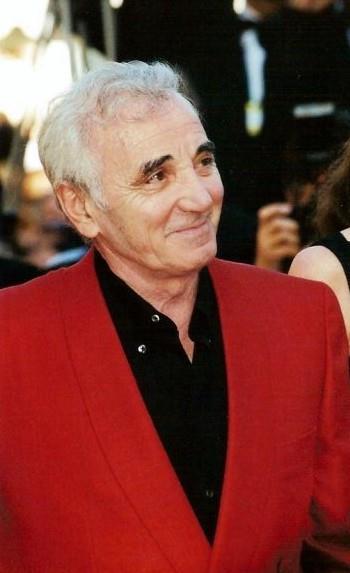

Charles Aznavour is impeccably dressed. He sits down to chat about his life and career in a downtown Montreal theatre. He’s wearing a beautiful, sleek black suit and black leather shoes. But to top it all off, he’s wearing a long, flowing purple scarf, draped around his neck and over his shoulder. Two things strike me as we shake hands: it’s impossible to believe he’s now 88, and this gentle, charming man is one of the gayest straight men ever.

Aznavour is widely regarded as one of the greatest songwriters and performers of the 20th century, having composed more than 1,000 songs, performed by a staggering who’s who of the entertainment world. Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, Bob Dylan, Petula Clark, Ray Charles, Lena Horne, Serge Gainsbourg: all have performed his songs and sung his considerable praises.

Born in Paris to Armenian immigrant parents, Aznavour was born in a trunk, as the old saying goes. His actor/performer parents led him to acting and singing at a young age. In the years after the Second World War, Aznavour became the protégé of Edith Piaf, who told him of her intention to go to New York. He said he longed to go but had no money. She scoffed, telling him he shouldn’t let money get in the way.

He hopped a boat to New York but upon arrival was interviewed by authorities who felt his poor English made him suspicious, thus he was detained briefly at Ellis Island. Finally, he was allowed into New York, where he lived with Piaf.

“But I couldn’t speak English very well, nor sing in it,” he recalls. “So Edith sent me off to Montreal, where she thought there would be work for me. But you know, back then, Montreal was mainly English, so they weren’t so wild about someone singing in French.”

But Aznavour persisted, and he found an audience there. His first-ever standing ovations were in Montreal. “This city is quite incredible. People take risks here. I think that three of the greatest cities for sheer creativity are London, New York and Montreal.”

Aznavour has long been noted for breaking taboos, writing brazenly and openly about sex in his songs. For years, the French government banned some of his racier songs from radio play. “Apres L’Amour” was one, in which he sang about post-coital bliss. Obviously, it’s not so shocking by today’s standards. His career got a boost in 1958 when the government lifted the ban and many of his songs could be heard by a larger audience.

In 1972, Aznavour wrote what would become one of his most famous songs, “Comme Ils Disent,” or “What Makes a Man.”

“I was the first to write a song in France about homosexuality,” he says. “I wanted to write about the specific problems my gay friends faced. I could see things were different for them, that they were marginalized.”

The song’s lyrics describe the life of a gay man, his crossdressing at Paris clubs by night, his close relationship to his mother. “I always wrote about things that others might not have written about. We don’t mind frank language in books, the theatre or cinema, but for some reason still to sing about such things is seen as odd.”

Aznavour did an unusual thing in 1950, when he was only 26; a turning point came when he sat down and wrote a list of what he considered his main shortcomings. They included “my voice, my height, my gestures, my lack of culture and education, my frankness and my lack of personality.” The list now seems so ironic, because he is renowned for his voice, his gestures and his height. In France, the five-foot-two singer is known simply as Le Petit Charles.

Aznavour has become something of an ambassador for the Armenian people, singing for fundraisers and appearing in Toronto-based director Atom Egoyan’s 2002 film Ararat about the Armenian genocide. But he says something surprising about his nationality: “I’m really a French person. That’s where I live, that’s who I am.”

If he has one anxiety about getting older, he says, “I know I’ll still feel like I’ll have work to do, that the things I want to do still won’t be complete. I still feel like there is so much I want to do.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra