Short films, the kind that Canadians love to create, are virtually unheard of in South Africa. As part of an ongoing committment to develop queer film there, Inside Out is showcasing some of the first queer cinema to arise in South Africa. The films are unusual, longer format docu-dramas, characteristic of many emerging African filmmakers.

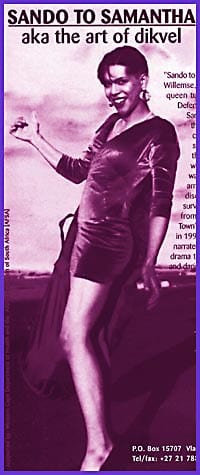

Activist Jack Lewis (once banned from his homeland) has created two innovative documentaries: Sando To Samantha: Aka The Art Of Dikvel (directed with Thulanie Phungula) and Dragging At The Roots (both shown, with Lewis in attendence, at 7pm on Tue, May 25).

“Oh my God! Priscilla [which means police]! I must report to the army and find a way to get disqualified!”

Sando To Samantha, made in 1998, is a bold film about a most eccentric life. Through a mix of documentary footage and dramatic recreations, we get to witness as Sando/Samantha, a coloured (or mixed-race) drag queen, comes to grip with military service and being HIV-positive. (Sando is one of the first South Africans to come out so publicly about his HIV status.)

We see Sando doing duty (he’s accepted by the men) and frolicking in an armoured vehicle with a barracks buddy. After being forced to take an AIDS test, Sando is told to leave the army because he’s HIV-positive. As Samantha, she returns to life on the hustle with friends.

Throughout, there’s a running dictionary on gay, moffie slang.

Sando To Samantha represents the emergence of works produced and directed by black South Africans and, especially, by women.

Lewis’s Dragging At The Roots documents the life of Kewpie, another coloured drag queen, who owned a hair salon in District Six more than 30 years ago. Overlooking Table Bay in Cape Town, District Six embodied the national consciousness of coloured identity and resistance. Moffie (or drag) concerts were a rich, vibrant part of life there during the 1950s and ’60s.

“Gays, who would meet and cruise at bioscopes [cinemas] or at lavish home parties, would jump off vans and do the Charleston,” Kewpie recounts. His narration is always powerful and entertaining.

Despite its historical perspective, the film avoids discussing how coloureds and blacks suffered in District Six: By 1966 it was declared white and bull-dozed to the ground two years later. Who’s interpretation of history do we get?: Kewpie’s or the filmmaker’s?

Despite this lack of context, the film is the first to shed light on Cape Town’s unique coloured moffie life (that was much popularized in such publications as Drum).

Written by South African Mark Gevisser, Greta Schiller’s The Man Who Drove With Mandela (at 7pm on Mon, May 24) is the compelling feature-length drama about theatre director and political activist Cecil Williams.

Played brilliantly by Colin Redgrave, Williams narrates as family members and significant South Africans (including black and white actors, directors and political figures) who came into contact with Williams, are interviewed.

“Did you know Cecil was gay?” That question, addressed to his colleagues, must have amazed South African audiences. Even Walter Sisulu hesitates, telling us that it was not a huge issue for the African National Congress.

In the South Africa of the 1950s, Williams’s white world of social privilege did not mix well with his homosexuality or his communism.

Williams knew Nelson Mandela – even attempting to smuggle Mandela back into the country after his escape to get international support for the liberation movement.

Rare home films, photographs and documentary film of the time are also used for startling effect. And there’s a lot of history brought to light. For example, the film shows how World War II affected South Africa and nationalism – even Williams’s desire to pursue his theatre career. “Blacks could only carry spears, not guns,” say Williams of the restricted roles available to blacks. Theatres became segregated and actors could not mix on stage.

The sights and sounds of Sharpeville are also emotionally wrenching.

Art, politics, theatre and fine acting come together to tell the story of apartheid through one character’s noble and heroic life in this significant film.

Eventually exiling himself to London, Williams did not survive to see the results of his work. But Mandela, as state president, did, when he signed the 1996 constitution that enshrined the principle of equality, including protection of lesbians and gay men.

These South African films are ultimately about belonging. The New South Africa teaches us about human compassion. And its queer and African filmmakers explore new territory, honouring those who fought boldly against the straight jacket of apartheid and for queer rights.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra