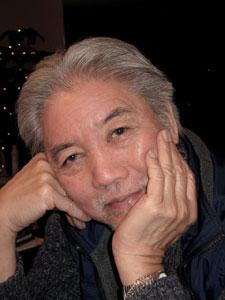

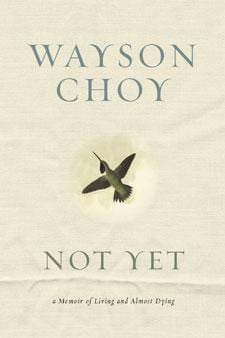

The good thing about nearly dying, says Wayson Choy, is that it “really focuses the mind.” The award-winning Canadian author suffered a combined asthma/heart attack in 2001. When he surfaced from the resulting coma his attitude to life was transformed. “I was overwhelmed by the numbers and kinds and kindnesses of people that showed up at the hospital,” he says. “From that trauma I emerged realizing that I was not alone.” The near-death experience — or “near life” as Choy prefers to call it — inspired his new book, Not Yet: A Memoir of Living and Almost Dying.

In the first chapters Choy recounts the dark days of his hospital stay. Flat on his back and semiconscious, he’s haunted by voices from his past. Choy grew up in the 1950s in Vancouver’s Chinatown, where being gay meant being a social pariah. “It was the dark ages of sexuality; I don’t think sex even existed for straight people in the ’50s!” he says with a laugh. “If one wanted companionship, or even friendship, there were very strict rules then about who will be with whom.” Family and friends scrambled to set him up with eligible young women — “‘Do we have a girl for him!’ they’d say” — and fretted that, without a wife and children, there’d be nobody to look after him in his old age.

Those criticisms lay buried for many decades; in the midst of hazy hallucinations, they returned. But as Choy gradually became aware of his surroundings, other voices took their place. “Don’t you dare die on me!” said one; “My God, he looks terrible,” said another. He realized that these people — the friends he lived with, the friends who loved him — had become his family. Surrounded by the sort of love that his blood relations thought he’d never experience, Choy was called back to a life that had new meaning. As he writes of that moment, “Listen, I told all those righteous voices that had warned me of a dire bachelorhood. I am not alone.”

The need to belong — to family, community, culture — is central to Not Yet. As a gay man living in a traditional culture, Choy’s quest for his own people began at an early age. “You find yourself looking for a place to belong,” he says, “and you are either creative in doing so or lucky. I was fortunate to be both creative and lucky.”

He first visited Toronto in 1963 and loved the city’s unique buzz. He’s been living here ever since. “Everybody has to find a place where they can look around and see their community, or a community of friends who are with them,” he says. “If you’re lucky they love you unconditionally and they become your family.”

Choy clearly has that kind of luck in spades. He’s an honorary member of two families — one in Toronto, with whom he lives full-time, and another in rural Ontario. He is godfather to all three children in the families.

And this is what makes Not Yet much more than a memoir. At the heart of the book is a powerful rethinking of what family really means. “Family is who loves you,” says Choy, “and that has nothing to do with bloodlines or religion or the rules of a traditional society.”

It’s an important message for everyone, but it’s particularly relevant to the gay community. After all, many of us don’t have the luxury of a supportive biological family behind us. “It’s not necessarily a choice for everyone,” he agrees, “but it is necessary for a healthy nurturance and it’s necessary because it’s more fun.”

The book is infused with Choy’s wry sense of humour. A routine physiotherapy session — performed by two handsome Adonises — results in a surprise erection: “the towel tenting, as if I were 16 instead of 62.” In fact, the sombre subject of nearly dying is merely the starting point of the book; it’s really about the joy of living.

This renewed commitment to the present also leads to a reconsideration of the past. Choy’s first-ever visit to China — to narrate a documentary on the philosopher Confucius — comes hard on the heels of his recovery. The writer is naturally curious to see if he feels a kinship with the country of his ancestors, but it’s not exactly a homecoming.

“I felt I was a tourist,” recalls Choy today. “I greatly admired the art and the history and the preservation of the temples, but I didn’t belong to them.” In fact, he found himself comparing the ornate pillars to Native American totem poles — a reaction that struck him as perfectly normal. “Why shouldn’t I say, ‘Ah yes, just like our totem poles?'” he says, with a smile.

Choy returned to Toronto with a renewed sense of his own Canadianness. His post-trauma quest for belonging led him right back to where he began — in a messy, book-filled attic room in Riverdale, surrounded by his chosen family. “I realized that all of us, especially gay people, have to belong to themselves and their own history,” he says. “Such histories have been closeted, but so what? It’s still your history that you need to profoundly discover and respect. If it’s a terrible history, remember you survived it and you’re a survivor.”

His personal discoveries have had an effect on Choy’s professional life, too. He’s now at work on a new novel featuring the characters he first introduced in The Jade Peony — his 1995 Can-lit classic that’s now in its 26th printing. The third novel in the series will be a kind of prequel, focusing on grandmother Poh-Poh’s life before she arrived in Vancouver. Researching the book brought Choy back, once again, to the Chinatown of his youth, where you were either “pure” Chinese or an outcast. He’s never felt so far removed from those beliefs than he does today.

“It would be nice if there came a time when we didn’t have to be ‘pure’ anything. Then we could just be who we are in our own history,” he reflects. “Love has no rules and, in discovering that truth, that’s where I’ve found my happiness.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra