Queer literature—and especially queer memoir—has historically leaned toward the morose.

Tumultuous coming outs. Experimentation mired in confusion or regret. Enduring violence or bigotry from small towns and families before blossoming into one’s most authentic self. These are the beats of the queer bildungsroman—books that are necessary, and that offer powerful tales of self-discovery and exploration, but are also kind of a bummer.

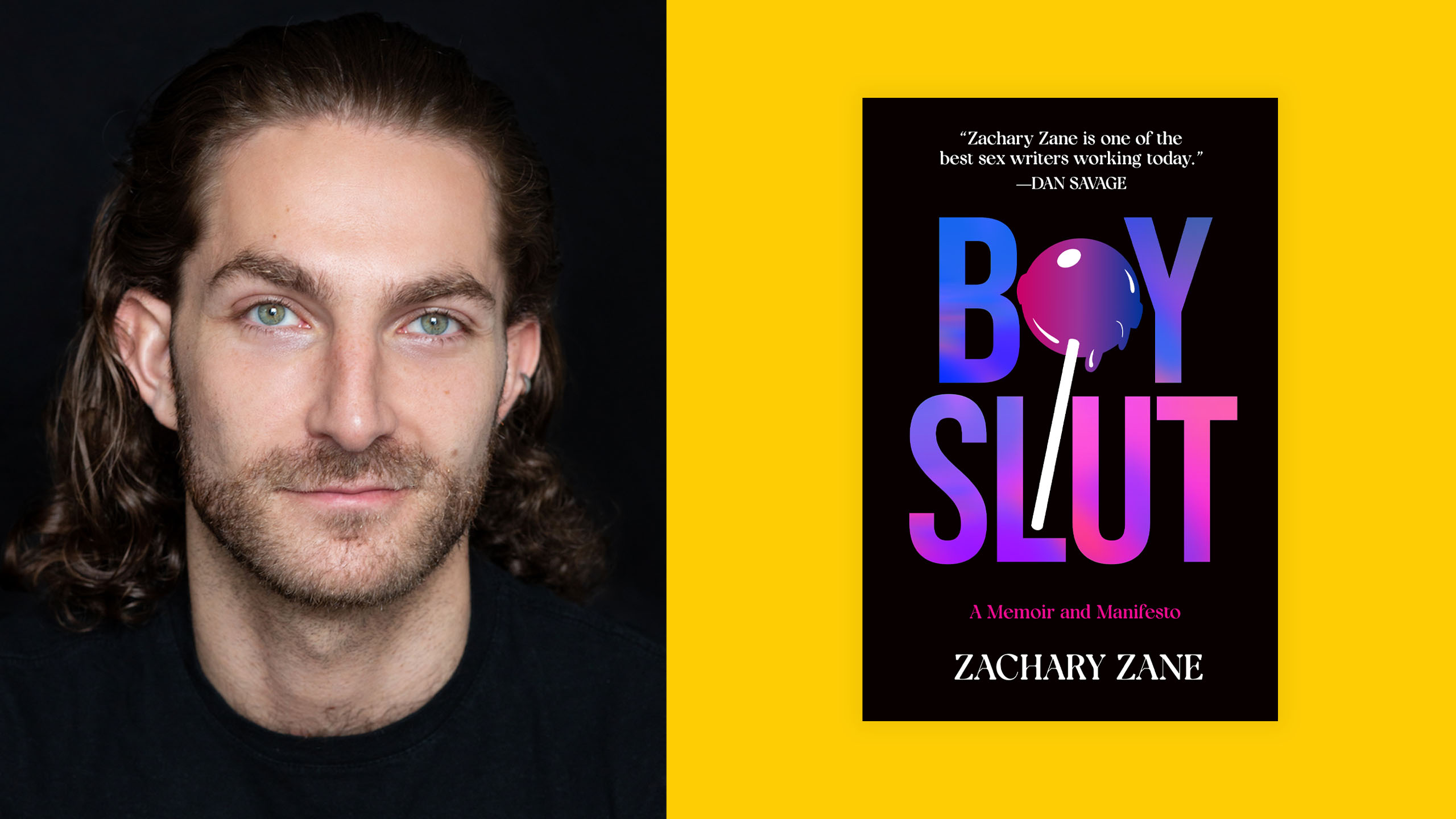

“We are long overdue for more modern, queer and sex-positive narratives,” says sex columnist and “bisexual mega-influencer” Zachary Zane in the foreword of his just-released book, Boyslut: A Memoir and Manifesto. Boyslut sees Zane channel the humorous and welcoming tone that popularized his Men’s Health advice column and other writings. This time, though, Zane reflects on his own stories rather than getting between the sheets of strangers’ lives.

And what may those stories be? With chapters titled “Cocaine Turned Me Bisexual” and “A Peg for Every Hole,” Zane is familiar with crafting an enticing lede. Yet those hoping for salacious tales from a man who, by his count, has had about 2,000 sexual partners will be left wanting (one can turn to Zane’s Substack for the steamier stuff).

Yes, Boyslut has plenty of anecdotes about kink, piss, sex parties and vomiting on dick—but those are outliers to what is, overall, a gentle and lighthearted invitation into the life of a person who has spent decades overcoming what millions more continue to struggle with: shame.

Interrogating shame is at the core of Boyslut. Zane writes about his OCD diagnosis and burgeoning sexual appetite as a child and young adult: a pairing that produced compulsive and unhelpful shameful thoughts, despite his upbringing in a liberal family and social circle. Through years of therapy, experimentation, heeding the counsel of others and—most radically—an unbridled embrace of his sexual interests, Zane has created a new world for himself. One filled with more sex, more fun and more freedom. Boyslut’s pages are the directions to that world.

Prior to the release of Boyslut, Zane spoke with Xtra about his journey to conquer shame, organizing 150-person sex parties and becoming one of the internet’s most prolific bisexual voices.

You’re known online for your Men’s Health column and other writings on sex and relationships. What initially put you on this path?

Nearly a decade ago, I was working as a smoking-cessation researcher and counsellor, and I had too much free time at work. I didn’t want to conspicuously fuck off on Facebook for hours; it’s just not a good look with people walking by. I realized I could write in a Word doc and no one was going to question it. I asked, what makes my voice unique? And it was me being a bisexual man.

At the time, there was a dearth of bisexual visibility. There wasn’t bi content for bi people. But I wrote this piece for the now-defunct site xoJane called “I Came Out as Bisexual and Now Can’t Date Anyone, Gay or Straight.” It was about how after I came out as bi I really thought the world was going to be my oyster, but women didn’t date me because they were afraid of my sexuality, and gay men were condescending and considered my bisexuality as a stepping stone. The piece went viral in a way that I was not expecting, and other publications reached out to me, looking for male bisexual voices. I did not think this was going to be my career at all, but it just showed how much we needed a bisexual voice.

In the book, you talk about having anxiety when you were younger and are still dealing with it today. How did that anxiety manifest when writing this memoir?

People get confused because I’m very sexually open. I have this non-fiction, erotic zine where I share very graphic, over-the-top, ridiculous, fun and horny depictions of me having sex. Yet this book was different: I’m discussing my relationship with my family, all the times that I hurt partners, when I was sexually insecure and closeted and when I had more elements of toxic masculinity. So this book was more vulnerable for me.

If you see me on social media, I don’t talk about my breakups. I don’t talk about my relationship with my family. I make jokes about anxiety and OCD, but I don’t tell you when I’m having an OCD loop. I’ve had extreme anxiety about the release of the book. I worried I wasn’t the best voice for the bisexual community, that I was going to get cancelled or that my grandma was going to read it and have a heart attack. But my anxiety has definitely gotten a lot better closer to the release of the book and I’ve gotten so much positive feedback.

You start the book with a glossary of more than 25 terms like compersion, fraysexual, metamour and so on. There’s a tension in the queer community between making sure everyone feels seen, but also not overcomplicating language. What do you make of that tension, and why start with the glossary?

I try to balance my writing style in a way where it’s not elitist—it’s very conversational. But as I was in the middle of a chapter, I found myself having to justify why I was using “ethical non-monogamy” versus “consensual non-monogamy.” I wanted to have everything in the beginning so people know what I mean when I use the word “bisexual” or “pansexual,” because there are so many different definitions. A part of me is like, okay, it’s a lot. Another part of me is like, you can learn 30 words. You’re a grown-ass human being.

Is there a particular word or phrase, either in the realm of sexuality or in kink, that you’re really trying to popularize right now?

“Fraysexuality” as a new label just blew up in a way I was not expecting. Fraysexuality is the opposite of demisexuality. Demisexuality means you only feel sexual attraction to someone after you have an emotional connection. Then fraysexuality is the opposite, where the more emotionally connected people are with someone, the less they have sexual desire toward them. This word was helpful for me to illustrate that no matter what your relationship is with sex, you can find a partner that compliments you. Sex is not the glue that holds a relationship together.

Another term I talk about in the book is “RACK,” which is “risk-aware consensual kink.” RACK posits that you’re allowed to take risks when you have sex. I give the example of always having a safe word when tying someone up, or having a pair of safety shears nearby because you don’t want to lose circulation. For choking, you often need a safety action because people can’t speak when they are being choked. Obviously, there are serious risks that come with choking and tying people up, but you’re allowed to take these risks with the consent of your partner.

RACK is contingent on information and knowledge. If you don’t know the risk you are taking, you can’t properly engage in RACK. I try to apply that outside of kink because we should have sexual freedom and autonomy to make choices, whether those choices are not wearing condoms or something else.

A major theme in the book is overcoming sexual shame. You write about how experiencing compulsive or violent sexual thoughts and fantasies is okay—and that people don’t have to pathologize every thought. How did you land on that perspective?

There are certain things that you should analyze through therapy and that require further introspection or reflection. But then there are times where trying to figure out the root of a desire or fantasy comes from a place of sexual shame. I don’t think there always needs to be a reason why we get turned on by a given thing. I think you can just enjoy it. What do you glean by knowing the root? What if there is no root?

Have you learned more about the connections between your OCD and these kinds of compulsive sexual thoughts?

When I was growing up, it was very intense. I remember there was a time I was on a soccer field at age nine or 10 and I imagined all of the grass mounds as boobs, and I started crying and had to be taken off the field. It really was impacting my daily life, my mental health and my ability to function in normal settings. And it’s a very common manifestation of OCD, but again, you only have that if you think sex is wrong. If we lived in a sex-positive society where there’s no sexual shame and you could be nude all the time, then that wouldn’t be how my OCD manifested, because it doesn’t work.

Are you worried about how your parents will react to this book?

I am terrified of my parents reading this. I’m absolutely mortified. They’re Jewish parents, they’re going to fucking read it. They’re nosy as fuck. I literally think I’m going to cut out two chapters of the book with a pair of scissors—one where I talk about my drug use and one where I talk about my kinks—and then be like, “this is for you.”

And what about romantic partners? Has anyone ever bristled at the thought of ending up in your writing?

Anyone concerned about that wouldn’t date me. I’m a bisexual sex writer who talks about getting DP’d. Most of the people I date are very sex-positive—and besides, I don’t write about people without their consent the vast majority of their time. If I do, I change all the details about them. Sometimes people actively want to be written about. I date people who have OnlyFans or are sex workers, so they are often like, “Please write about me. Link to my OnlyFans. I want this additional press.”

You write in the book that you enjoy both paying people and getting paid for sex. Can you expand on that?

If I want to do something specifically kinky, or there’s someone who’s really attractive and they are a sex worker, I’m more than happy to pay. As for getting paid, I do it because it’s fun, and can be rewarding.

I remember a man I met up with in Portland a few years ago who was a prominent, wealthy doctor. He liked me because we didn’t just have sex, we also talked—which he hadn’t experienced with other sex workers. He shared that his partner died from AIDS in the 1980s and he’d never been able to love again. My heart fucking broke in that moment and I had to try not to cry. I held him and it was quite a powerful experience, and something I would not have been able to experience had I not done sex work.

The “Boyslut” brand began as a sex party you hosted called BISLUT. What advice would you give to folks who want to host their own sex party?

Oh my god, BISLUT was a lot of work. I did it to create a bisexual space and fill a void. Usually if it’s a mixed-gender sex party with women and men, the guys don’t really hook up with guys. And then with gay sex parties, it’s just men hooking up. There wasn’t really a bisexual space and that made it really easy to come, no pun intended.

We had to get the right staff: bartenders, security, clean-up—and we had consent monitors. I wrote a consent speech and then my friend would literally read the speech to groups as they walked in.

Really make it clear what the vibe is. A sex party is so broad, the more you can communicate who this is geared toward the better: be they polyamorous, kinky or swingers. Also make it really clear what the norm of consent is in your space. I talk about this in the book, but is this an enthusiastic consent space where you ask before touching? Or is this a more traditional dungeon space where a guy in the sling, face down, ass up, doesn’t want you asking if it’s okay to touch him. He wants to get fucking banged.

A thing that I did for my parties, too, is always having friends who are fire starters. No one wants to be the first person to start having sex. So having people you can go up to and say, I need you to start this party—I need you to get up, start sucking each other’s dicks, fucking each other and creating that space.

The book largely centres on exploring your desires, wants and kinks. What’s some guidance you would give folks about how to take that journey deeper into their own sexuality?

Allow yourself to explore things knowing it doesn’t define you. Labels can be extremely helpful and, for me, using the word bisexual has helped me feel part of a community. But for other people, that’s not necessarily the case. Let’s say you’re a man hooking up with another dude and think, shit, does this make me gay? Does this make me bi? You can’t even be present in the moment because you’re obsessing about your label. But if you decide this isn’t for you, that doesn’t make you any less straight.

That also applies to gay and queer men who have been out for 10 years and then have a sexual experience with women and are thrown into an identity crisis. It’s a common question I receive from especially older gay men who are worried about confusing their partners or being ostracized by gay friends. The truth is you might be, there’s still a lot of bisexual stigma. I still think you should come out and do this because this is something you want to explore and be able to be true to who you are.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra