The American South, more than a region, is a loaded cultural statement with an undeniable influence on the hearts and imaginations of people all over the world.

When I mention my Southern heritage to people it invariably turns into a conversation laden with stereotypical images of the South, from the racist, slave owning, Klansman to the gun-toting, Bush-boosting Bible-thumper.

This negative perception is countered with sepia tones of antebellum mansions, drinks on the porch and a litany of great poets and writers.

My father was from the South; through him I am Southern. As I get older I begin to realize that I am the collective sum of the challenges, work, ambition, failure and hope of my Southern ancestors. Yet, I am disconnected from them.

My father was in prison throughout my childhood. I only met him once, for four hours, when I was 21. Five years later, I’d give anything for another four hours.

His life was marked with sadness, from its inception in the backrooms of the Phenix City, Alabama brothel where he was born until his death in an Indiana prison.

Much of his is a very sad, depressing story — at least the parts I know. I long to have a positive, living connection to my father’s homeland. This month, I fly to Alabama for 10 days, but before I go I need to better understand Southern culture and nuance. In case I don’t find a positive or beautiful story from my own heritage I’d like to borrow one or two from somebody else’s.

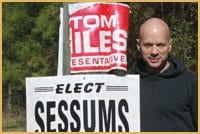

This summer I’ve read several books about the South, none more useful to me than Mississippi Sissy by Kevin Sessums. He presents what I believe to be a balanced and affectionate portrayal of his family, homeland and culture.

“We may not be able to read in Mississippi but we sure as hell can write,” says Sessums, reflecting on Southern stereotypes.

“It’s a great place to be from and usually when you tell people you are from Mississippi it either starts or stops conversation,” he continues. “Either they sit down next to you on the sofa or they walk away from you and don’t want to have anything to do with you.”

As the title suggests, his early childhood was marked by his “sissy” tendencies which drew the ire of his father, a professional athlete, and the wholehearted support of his mother, a lover of literature the arts.

She handed me her pen and a piece of her stationary. “Write it down. Write down that word. S-I-S-S-Y.”

I obeyed and wrote the letters as large as I could across the paper.

“Now, whenever anybody calls you that again you remember how pretty that looks on there. Look at the muscles those Ss have. Look at the arms on that Y. Look at the backbone that lone I has. What posture. What presence. See how proud that I is to stand there in front of you.”

I find that in popular gay culture, images of masculinity and “butch” mannerisms are put forth as sexual ideals. In personal ads on the internet and in the papers, men often advertise the fact that they are “straight acting.” In Mississippi Sissy Sessums openly celebrates his sissy tendencies. His words render that feminine side of male beauty incredibly sexy.

Sessums was definitely not straight acting as a child. His sissy tendencies, to a certain extent, defined his relationship with his butch father.

“My earliest memories were throwing things in people’s faces and realizing the power of the appalling gay,” he tells me. “Like when people, adults, looked at me as a child, the look in their eyes of ‘Oh my God that’s a creature.’ It was almost as if I wasn’t a human, and they were almost afraid of me and because of their fright at my sissydom. I felt power.”

When he was three, Sessums asked his mother to make him a skirt, which she happily did. When he pranced around for his father in it, his father angrily tore it off him and set it on fire in a barrel saying, “that’s what happens when boys try to be girls.”

These experiences did not hinder his sissyness. “I was in touch with the power of it and I’ve always flung things in people’s faces.”

Nowadays Sessums tries to butch it up and “not be a sissy,” but says that when he was younger he ran around unedited.

“You’re not allowing the world yet to dictate who and what you should be and how you should act,” he says of his youth. “I always revelled in the difference that I felt, and I used it as a weapon.”

By the time he was eight, both his parents were dead. His father died in a car wreck and his mother succumbed to cancer a little more than a year later. He was raised by his grandparents, whom he called Mom and Pop. They were a Christian couple who frowned upon his mother’s liberal leanings and his own sissy tendencies.

“I realized very early on that the world is a very complicated place growing up in Mississippi [in] the time I grew up there, in the 1960s — especially because of the people who raised me, my grandparents,” he says. “If they said the ‘N’ word once, they said it 50 times a day. They hated civil rights workers and they were sort of backwoods, lower-working-class people, and if you saw them in a film in an objective sense, listening to them talk and their social attitudes, they’d probably be the bad people in the piece.”

But they were not bad people.

“They were the people who raised me, took me in and saved me, really, and gave me unconditional love,” Sessums says.

“I had to look at them and find the goodness in them. They were bigoted, prejudiced people. They were. We fought about that a lot when I was growing up and stuff. But I had to look past that and I think I did a well-rounded portrait of them in my book.”

While watching a Billy Graham revival with his grandmother at age 11, Sessums broke down and cried, saying nobody loved him.

“Oh, honey. Don’t you say no such thing. Don’t you dare,” she said. “You ain’t nothin’ but loved. You just have t’learn how t’feel it. There’s somethin’ inside you that’s always fought bein’ loved. I ain’t never understood it. I just know it’s fact as true as anything Billy Graham can quote letter perfect from the Bible. Don’t fight it so. It’s a fine thing: to be loved. You go on and feel it. No more fightin’ it off.”

Her first pounded me.”You listen t’Mom. Stop a’cryin’. Stop it now. Shshsh…”

These days, Mississippi is like a foreign country to Sessums, who hasn’t lived there for over 30 years. His brother and sister, however, both have successful careers and lives down there.

“When I do go back, I can stay three of four days and then I have to get out because it gets sort of culturally oppressive,” he says, “because it is the reddest of red states. Conservative still. But I don’t think it’s my role in life to defend Mississippi. I grew up there. It’s a great place to be from.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra