Dave Deveau smiles and shakes his blond head as he recalls being commissioned as a teenager in Toronto to write a monologue for young would-be voters exploring some element of democracy.

He can’t fathom why he chose to explore gender, or how he created the character of Nelly, a gender fluid 15-year-old isolated in the hell of suburbia.

But one principle has been the driving force in expanding that original 15-minute monologue into the full-fledged play, Nelly Boy, which makes its Vancouver debut Oct 23 at the Performing Arts Lodge.

“In theory, we should be free,” Deveau says.

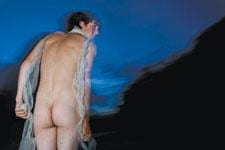

Freedom to be oneself is at the heart of Nelly Boy’s story. The drama focuses on Nelly, who was born male but refuses to be boxed into either male or female and lives instead in the nebulous gender space in between.

A powerful story unfolds after Nelly is found naked on the side of a highway and brought in for questioning by police.

At its core, the play is one of gender exploration — and what happens when someone challenges society’s rigid expectations of gender.

“I think it really is interesting how anxious people get when they can’t identify a person,” says Nelly Boy’s director, Cameron Mackenzie. “Somebody walks in and the first thing we do is assign them gender and we’re like, ‘Phew, that’s out of the way.’

“But we only get a sense of how instinctual and automatic that response to label them is when we can’t actually put a label on them. And, then it’s like we can’t breathe. As soon as they can’t find that gender pronoun, people freak out, they lose their shit.”

“On a day-to-day level, we’re talking about decisions like which public bathroom is safer to use,” Deveau adds.

Both Deveau and Mackenzie identify as male, but each admits to fielding internalized questions about gender as part of the coming out process.

“I don’t want to say Nelly reminded me of myself, but he’s a smart-ass kid, and I love smart-ass kids,” Mackenzie says. “Kids who are loud and just going to say what they think, and who acknowledge when they don’t fit in. I came out as gay when I was 15 and Nelly’s 15, so there was some kind of unified ‘Yeah, you go brother/sister.’”

“Certainly as a young gay man I wrestled with ‘What is the notion of masculinity?’” Deveau says. “Am I performing my sexuality by being a slightly more flamboyant male? I fortunately have never wrestled with not feeling male, so I think in a way the piece must have come out of some kind of subconscious question about what it feels like to not belong in a particular role that in this case you’re not biologically suited to play.”

The question of what makes someone male or female made international headlines after South African runner Caster Semenya, who’s broken many women’s world records in the last several months, was accused of not being a woman in August.

Semenya, who was raised as a woman, is currently being subjected to a barrage of gender tests, the first few of which have indicated that she’s intersex.

“It speaks to a culture that has these prescribed notions of ‘That’s a boy, I can treat that person this way; that’s a girl, I can treat her that way,’” Mackenzie says.

“I’m a drag queen as well, and certainly for me that question of ‘How much of a man am I?’ was very strong, ” he continues. “I am a little bit more flamboyant and feminine, and when I’m a woman I do pass as a woman. For me at Nelly’s age, it was like, ‘I know I’m a guy, but what does that mean to me as a gay man? Do I now need to cross my legs a certain way?’”

Deveau and Mackenzie hope that by tasking a 15-year-old character like Nelly with some of these weighty questions, particularly the notion of a gender spectrum, honest dialogues about gender, sexuality and equality will flourish openly.

Deveau says issues around gender have evolved a bit in the five years since he created Nelly, but not as much as some people would like to think. He recalls one critic who saw a small staging of Nelly Boy in Toronto who claimed that “most people are past the issue of gender.”

Real life examples like the investigation into Semenya’s sex, and the countless trans people who are marginalized by the he/she question every day, suggest otherwise.

“We should be able to choose how we fit into the gender landscape as opposed to just accepting one thing or the other,” Deveau says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra