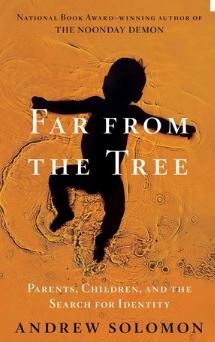

Far from the Tree tries to make a case that 'different' young people share similar experiences, regardless of the specific identity.

There are, it should be noted, more pages in Andrew Solomon’s sprawling book Far from the Tree than words in this review about it. Solomon, a gay man who inherited a substantial fortune, has attempted to use a few pounds out of the tonnage of his privilege to give serious consideration to questions of children who are “different.” The book examines children with dwarfism, children conceived during acts of rape, children who are autistic, schizophrenic, D/deaf, prodigies, criminals, disabled – and transgender.

Solomon’s point, explained at length in relatively crisp prose, is that some identities are what he terms “vertical”; that is, we get them genetically or culturally from our parents, and some are “horizontal” – we share them with other people in the world, but not our relatives. It’s within this matrix that he justifies his choice to treat such a wide variety of family experiences as variations on a single theme (it’s also worth noting that Solomon himself reports that some of the families in the book expressed significant discomfort with the implication that other kinds of families in the book were in some way the same as theirs).

The writing here is good. It’s much more likely that you’ll put the book down because you’re frustrated with someone’s parents or with Solomon’s conclusions than out of boredom, even as the page counts reach into Harry Potter territory.

The book also includes some viewpoints that feel satisfyingly complicated. Solomon has clearly resisted the usual imperative about dumbing down difficult work and presents some very nuanced, and ultimately very human, portraits of the choices families make on behalf of their children. To be sure, the reader may not always identify with or agree with those choices, but they are rarely flattened for the sake of simplicity.

What does seem to be flattened here, in the association of all of these identities and experiences of children who are in some way profoundly “other,” as the parents understand it, is the piece about external perception. Solomon makes the case throughout his book that at the end of the day all horizontal identities in children have similar qualities for the parents – they’re all a mixed blessing, in essence. It seems clear that Solomon imagines this to be a startling idea, to say that a prodigy child and a dwarf child and an autistic child are all more or less the same family experience. But the argument seems blind to cultural approbation. The personal growth process of all of those parents may indeed share similar touchpoints, but Solomon – who seems to have done more of the interviewing in his own social stratum – has all but completely ignored the effect (and experience) of external feedback.

Far from the Tree is as complicated as its topic. It tries to make a case that “horizontal identity” young people share similar experiences regardless of the specific identity.

To that end, it uses direct quotes from the young people in question, but only some of them (a choice to appreciate in the transgender chapter, where young people’s voices are present, and resent in the disability chapter, where they are silenced), and probes at the parents, seeming to soothe some and trouble others by design.

It’s also not at all clear that Solomon has done enough in understanding or discussing what cultural forces shape the choices the families are making or have made on behalf of their children – what do we value, as a society, and how far are we willing to go to create a version of what we experience as “normal”?

It seems true, however, that for families with children they experience as being profoundly different from them, Far from The Tree is going to offer some comfort and some food for thought, even if it’s not all they could be eating.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra