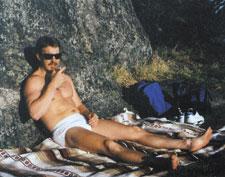

Newly out at Lighthouse Park. Credit: Courtesy of Brad Teeter

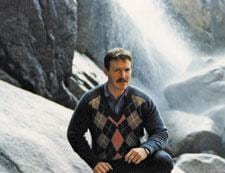

Last night in Guelph. Brad is on the bottom. No one is out. Credit: Courtesy of Brad Teeter

On the beat by day, on the prowl by night. Credit: Courtesy of Brad Teeter

Family portrait, with young Brad on the far left. Credit: Courtesy of Brad Teeter

1985

Bursting into the Village

Bursting is an odd way of describing an unnoticed entry into a place. But as I make my way down Davie St in Vancouver’s West End, I am miles beyond hopeful or relieved. I am frantic.

After years of scratching out a sex life in and around stinking toilets and other dank spaces, I have arrived at a renowned gay meeting place. On foot, after a white-knuckle winter drive through the mountains, my legs won’t move fast enough.

The promise of new freedoms on the coast prompted the continuation of a westward journey that began in 1979. My lengthy stop in Southern Alberta is over. I have packed the trunk of my Dodge Diplomat and headed for the hills.

Hedges as tall as trees line the street into Vancouver’s city centre. I’m feeling out of place in my heavy coat and boots. It has rained but now the sun is shining. People are dressed in light coats or sweaters.

In West End clubs, George Michael’s “Careless Whisper” has gay couples smooching to a story of infidelity. Michael laments that he’ll never dance again after the loss of a lover he’s cheated on.

But for me, the dance is just beginning and, as Tina Turner observes in her hit single, love has nothing to do with it.

At the park, at the Y, in shaking bushes, on the busy staircase of the gay bookstore, at that naked beach — around every blessed corner — there is a possibility.

Here, two towering apartment blocks identify as gay, not merely tolerant or friendly, flags flying year-round, rainbows projected into the Christmas night sky.

And here, a fruit loop is something beyond a breakfast cereal. Even police and firemen casually make reference to the Fruit Loop cruising area, Vaseline Towers and Stack of Fags, landmarks not noted in tourist guides.

Bold sexual overtures that served me well with “straight” men in Alberta don’t work in the West End. Here, gay is the expected orientation among men and women of a certain look or manner. When I try to chat up a handsome fellow on a street corner, he nonchalantly refers me to a gay pub around the corner. “You might want to check that place out, buddy,” he says, smiling, feet moving.

News of the plague is plastered everywhere. Angles, Vancouver’s gay newspaper, is filled with horror stories. Rock Hudson has just died of AIDS and Ronald Reagan — who has never uttered the word AIDS — has taken the oath for his second term as US president.

Sometimes, I’m certain AIDS is creeping through me. But mostly, it’s beyond me, around me, above me, beneath me, too ugly to be in me.

Word of the plague first reached my ears in 1983, two years before my arrival in the West End. At the time, I was working as a reporter for The Herald in Lethbridge, a small city near the Montana border. The story unfolded slowly, bits of troubling news and than a cascade of deadly losses.

By then, the gay community had mobilized into small, volunteer-run organizations, with AIDS Vancouver and the AIDS Committee of Toronto incorporating as the first community-based AIDS organizations.

No one knew the cause of AIDS. Religious nutcases swore it was God’s way of punishing homosexuals. Even the science world offered crazed, oftentimes lethal guidance.

On doctors’ orders, guys popped toxic pills like popcorn, beepers signalling their next dose in hushed movie theatres.

Sexual meeting places were closed across North America and throughout the developed world. All gay sex acts short of masturbation were demonized.

Meanwhile, I had long been negotiating sexual liaisons in and around a Calgary bathhouse, my lovely ass up in the air. If getting fucked and sniffing poppers caused AIDS, I was doomed.

But on my first day in the West End, I am wildly alive. Slow the fork, I tell myself at a greasy spoon on Granville St where I slop up toast and eggs. I have no plans, but I’m in an awful hurry.

As I wait for an apartment manager on Barclay St, I worry that not having a job might make apartment hunting difficult. But the problem I run into has nothing to do with my employment status.

The tall, 50ish landlady at the three-storey walk-up tells me homosexuals have been chased from the West End.

“They’re gone, and it’s a good thing too,” she says, sniffing the air.

She is confusing us with prostitutes. I had read about a Shame the Johns movement led by a gay fellow named Gordon Price. After considerable bullying, the prostitutes had fled to a less affluent part of town, the “shamed” Johns scampering after them.

“We were fed up and now it’s done,” the landlady huffs. “They’re out. ”

“Who’s out?” I ask, finding it hard to get my mind around such stupidity.

“The homosexuals. Good riddance is what I say. Everybody knows it’s a sin, says so right in the Bible.”

I’ve come too far to hear such nonsense.

“I’m gay,” I tell her.

“What?” she asks, stepping back, hand to heart. “You are… not one of them.”

She trails after me, eyes on my back as I close the door behind me.

***

1977

Hand job, blowjob or intercourse

The plan was to treat myself upon arriving back in Toronto. A stash of money from my summer job set aside for a sexual adventure on my way back to Guelph.

It was time to test my equipment.

Deep breath, then I’m prying open a heavy door under a neon sign flashing “body-rub parlour.”

A stout man asks if I want a private session. I’m directed to the massage area, rank with pungent smells, tiny chambers set apart by strings of beads.

A thin woman in panties and white blouse welcomes me to her cubicle before sending me to shower at the far end of the maze. Now I’m back, dripping, towel in hand. She rhymes off her service menu twice, like a waitress repeating the day’s special to a stunned customer. There are three options: a hand job, blowjob or intercourse.

Intercourse sounds good, I tell her, then… “Maybe just a hand job.”

“It’s okay, baby,” she coos, draping an arm around my neck, pulling me close. “You can fuck me for the blowjob price.”

I’m the guy with the big grin on the bus back to Guelph. I got hard, stayed hard and blasted off a good one. All man, destined to follow in the footsteps of my older brothers. There will be girlfriends, then that special woman, a wedding and a couple of kids. Won’t Mom be proud!

The dream lasts 45 minutes. As the bus pulls into the Guelph terminal, I’m chatting up the muscular fellow in the next seat.

***

1974

Branded in the locker room

I’m in my high school locker room peeling off my shoulder pads when suddenly a heavy penis is dangling in my face. It belongs to Mike Lorenzo, an Italian with thick legs who never does anything quietly. He’s standing over me, dangling.

“You’re a homo aren’t you, Teeter,” he shouts, laughing. “You’re so stinkin’ polite you’ve got to be a homo.”

Last in line at the water fountain, a ghost in the showers, I don’t want to be noticed. But Lorenzo has noticed. Now he’s entertaining the boys. I watch him saunter to his locker, even his fur-rimmed asshole smiling.

The thing is, Lorenzo likes me. He’s joking with me. He just doesn’t get me.

I really am one of the ones we call disgusting names. Even back in elementary school, before we understood, words describing the likes of me were used like swords on the playground.

“You’re a homo,” we shouted, pushing and clouting each other in our snow-bank battles. The words were meant to poke, stab. A homo was a filthy thing, worse than having cooties.

***

1976

Hitchin’ a ride

“Will you hit me if I ask you something?” he asks, moments after I climb into his vehicle.

Sticking my thumb out is faster and cheaper than taking the bus. But this morning, I am offered more than a ride to the college. His hands grip the steering wheel, eyes straight ahead.

I know where he is headed.

There is an offer of a blowjob.

“I won’t hit you, but I’m not interested,” I say.

We drive through a wooded area, brilliant yellow and streaking red maple leaves backlit by the morning sun.

Within minutes of arriving at the college, I return to his opening remark. “You can do it, as long as I don’t have to touch you.”

He parks the car by a hedge, flipping around his cap before joining me in the back seat. It is over in minutes.

For a few days, I scan the roadways, worried sick that the nameless man will find me, blurting out the details of our deed in front of my college buddies.

But before the month is up, fear gives way to a deep longing. Thumb out along the roadway, I’m hoping for more than a car ride.

***

1982

Trolling round the toilets

After evening assignments at The Herald, I prowl for men in downtown Lethbridge.

It’s 1am and I’m scanning the streets. Round and round I go, hunting for wobbly men exiting the pubs.

Even on Sunday afternoons, tumbleweeds bouncing down Main St, I’m making my rounds, looking for new arrivals at the bus depot, young men needing a hand with their luggage.

Lunchtime finds me trolling at a smelly hotel washroom. Most days, the toe-tapping Marvel twins arrive ahead of me, the smell of piss and shit overridden by their nauseating perfume. One of the boys — I can’t smell them apart — is always strategically planted in the peephole suite.

But on this day, there is no Marvel in nose range, and I’ve snared a hot one: square jaw, big, nervousness showing in his whisper and shallow breathing. He is young, about 22, dressed in black with an odd haircut.

A Hutterite. We assume the position, and he’s suddenly confident — the way I like them — hips swinging, grunting, my head banging against the stained toilet.

Back at the Herald office, I reach for the phone, grimacing. My underwear is sticking. Another reporter passes by, puts his hand on my back, asks about last night’s hockey game.

I bristle, brushing him away. “Don’t touch me, Tom.”

The man’s Bible-toting, filthy-talking persona reeks of hypocrisy. But mostly, I’m worried he’ll notice I smell like a dirty toilet.

***

1973

The beach boy

In our mid-teens, on holiday, my sister and I develop a crush on the same boy.

We are at a beach-town roller rink, and we are both captured by Bernie, a tall fellow with a tan any boy of the sand would be proud of, his long legs sweeping, dancing to the tune of the Janis Joplin song “Me and Bobby McGee.”

Bernie is always out front or whizzing by. I catch bits of him — an arm, his half-laced skates, that tight butt — as he floats around the cement floor of the oval-shaped enclosure.

Cathy and I don’t speak of our interest in Bernie. But upon arriving home from an afternoon swim, I find my sister cradled in the arms of my two older sisters, talking of first romance. I watch through the open cottage window.

Cathy is sprawled on the living-room floor, her head in Sharon’s lap, Anna holding her hand. Cathy’s cheeks are flushed, eyes bewildered. I have never seen that look on her face before.

“I remember my first time,” Sharon says, stroking Cathy’s forehead. “You will never forget this summer. Enjoy it. It’s the best part of growing up.”

Bernie invites me to overnight in a tent with him in a nearby field. Finally, the sun sets and we’re alone, roasting hot dogs by the lake. Bernie drops his shorts, racing into the water. I’m on his heels, splashing, chasing his glorious, white bum. He has more pubic hair than I do. Later, towels draped around our waist, we walk, shorts in hand, along a gravel road to our tent.

I’m matching Bernie’s quick pace, sharp stones stabbing my feet. He’s on a grassy strip beside the roadway, flinging wet hair out of his eyes.

My towel lifts. I’m hoping he will notice. Fleeting glances at Bernie’s crotch, but I can’t see any action. No excuse to stop and stare.

In the tent, he is beyond reach. We talk for hours about sex, noting that some guys are better hung than others. “My friend Josh hangs his over his shoulder,” says Bernie.

Weeks later, Bernie shows up unexpectedly at my home in Guelph. The two of us hike along the railroad tracks to the river. When we return, my sister Anna lashes out at me. I have deprived Cathy of alone time with Bernie.

“You are thoughtless,” says Anna.

I am surprised. The idea of sharing Bernie with my sister Cathy didn’t occur to me, not even for an instant.

***

1979

Westward bound

It’s January 1979 and I’m heading west despite a front-page Toronto Star headline days earlier warning: “Don’t go west young man, they don’t want you.”

The newspaper is referring to the hordes of young people travelling to Alberta to land jobs in the oil fields.

“Don’t listen to what the paper says,” banner editor Marion Duke barks in her jovial, matter-of-fact voice as I bid her goodbye.

“Follow your heart,” she said. “The hell with the paper.”

And so, after a marathon drive through the northern states, I’ve joined the Alberta newcomers.

It’s February and crackling cold under a big, blue sky. I walk through dry snow to the city centre past pubs where men will come later for a beer and talk of new adventures.

But as I sip my morning coffee at a hotel café, I’m surrounded by sombre faces.

The new arrivals are in retreat. They are lined up at pay phones, telling friends and family that they are too late. The job market has dried up. They’re going home.

But my travels have nothing to do with the oil patch, and going home is not an option.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra