At the recent town hall meeting at The 519 focused on the issue of missing LGBT people in Toronto, there was a strange moment.

After the 150 or so people were split into groups to discuss the challenges for queer men to stay safe, people shared some of their conclusions.

“There are concerns about the park out here,” said one man about Barbara Hall Park in the Church-Wellesley Village. “There’s lots going on out there and it doesn’t seem to be taken seriously and we’d like to see that happen.”

He continued: “Other areas we discussed was the Toronto community housing co-ops a little bit more surveillance would help there.”

A number of other people discussed the need for an increased police presence on Church Street.

If you’ve been to many neighbourhood meetings, you know what these statements mean.

It means there’s too many homeless people or sex workers or addicts or mentally ill people hanging around in the park. And as for asking for surveillance of Toronto community housing, we need to keep a closer eye on the poor, racialized people that live there.

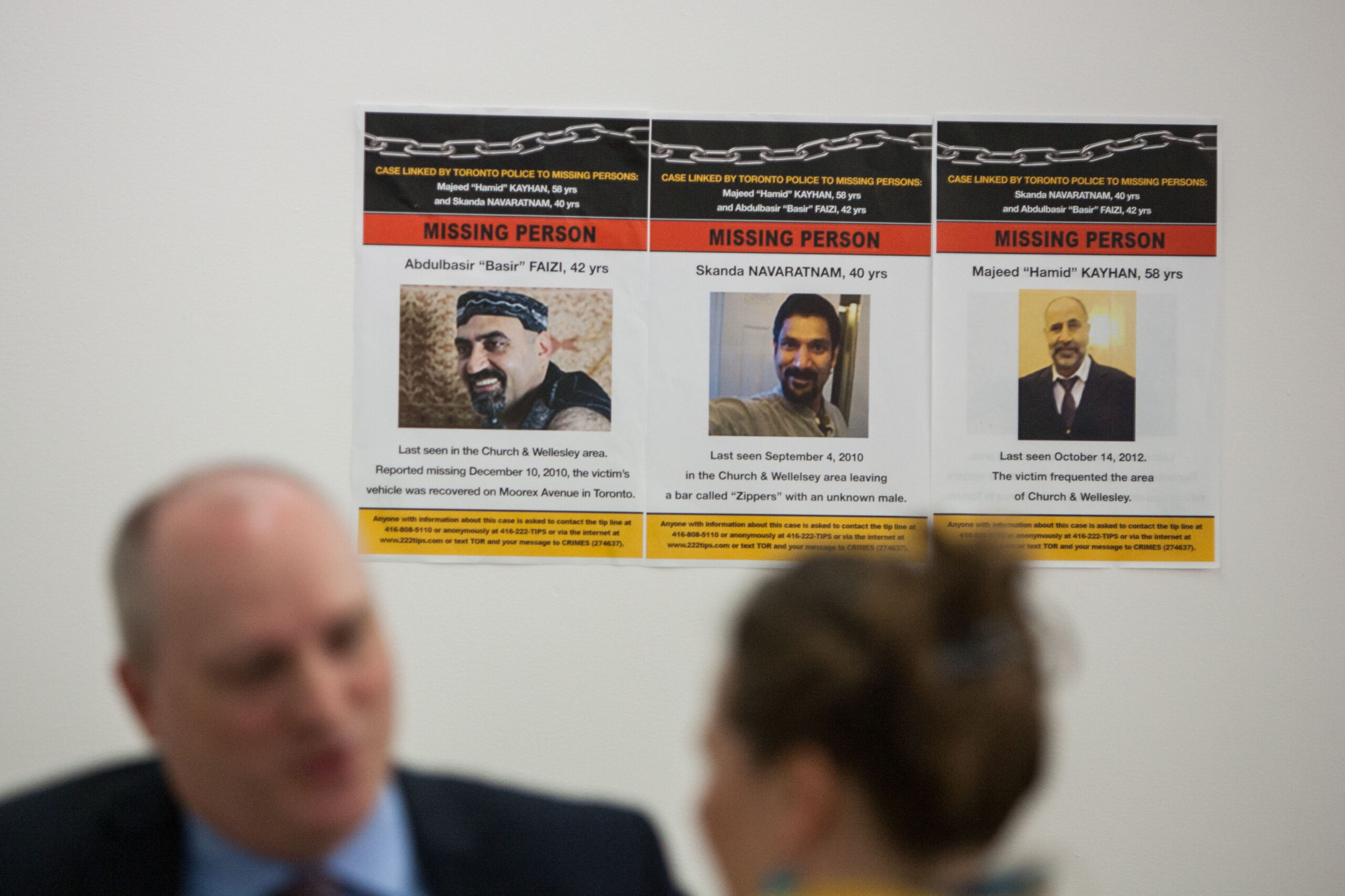

It was a strange moment because there is absolutely nothing to indicate that the disappearances of five gay men from Toronto’s downtown east had anything to do with people in the park or living in Toronto community housing.

In fact, the overwhelming assumption by most of the people in the room was there was some kind of sexual predator going after gay men, either through dating apps or at bars. (But let’s be clear — the police have said they have no evidence that any crime has taken place or that any of the disappearances are connected).

Those two thoughts are pretty much incompatible: to link these disappearances with street crime or loitering is simply illogical.

What all of this reveals is that safety and the perception of safety are often very different things.

The Toronto police ended their highly controversial TAVIS program, which flooded high-crime neighbourhoods with police officers, in January 2017 because it was ineffective and alienated the communities it was meant to serve.

I don’t want to imply that everyone at the meeting was in favour of these kinds of tactics. In fact, many people spoke about the need to think about these disappearances in conjunction with missing Indigenous and trans people.

But asking for more police on the streets, or for surveillance of Toronto community housing, undermines any sense of solidarity, since for a long time, Black, Indigenous and trans Torontonians have said that the police are often a threat to their safety.

While the police are by all accounts taking the disappearances of these men very seriously, until they deal with the many systemic issues that plague the departments, more police on the streets is not a solution.

And to target Toronto Community Housing was especially thoughtless because four of the five men who are missing are racialized.

Many people provided good suggestions for helping to increase safety, including compelling bars to have drug-testing kits available, and finding ways to provide closeted men ways to report their location.

But there’s no evidence that putting the most vulnerable people under increased police scrutiny makes anyone safer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra