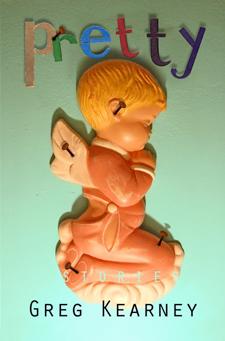

Aww, look. What an adorable cover pic. A little blond angel boy saying his prayers. But wait — are those nails? Oh my God, rusty nails? Piercing the sweet darling’s foot and thigh and ear? And — gag — his tender little angel wings? And above the skewered tyke, in childish cut-out letters, the title: Pretty? What kind of book is this?

Welcome to Greg Kearney’s fictional fun house. You think pierced innocence is funny? Try the other end of life’s arc.

“Weak and mildly tachycardic after his orgasm, Cliff felt his way along the kitchen wall, leaning. He’d lost ninety pounds since the heart attack. The leftover skin on his buttocks hung like ancient drapes.”

That’s paragraph two of the first story, “Mary Steenburgen.” In paragraph one, Cliff comes “in the cleaning woman’s eye,” after which his wife, Denise (one of the humping threesome), makes a stack of roast beef and pickle sandwiches for hubby and Clara, the cleaner. I started chuckling at the part about the ancient drapes, and the chuckles just expanded, and I had to put the book down until the fit passed. That was page one.

So they get the crack-head cleaning lady tidied up and (reluctantly) cabbed home, and Denise announces that she will allow another threesome if she gets to set the rules herself. She outlines her preferred female type while Cliff nervously takes his pulse.

In “What to Wear,” Ron goes to Woody’s to hook up with a hunk he met online. The guy arrives, gives Ron a cursory eyeballing and starts doing a weird, rapid smiling/not-smiling thing.

He warns, “I’m candid.”

His candour is all about unfortunate drug reactions and “deformity.” He pats Ron’s hand and leaves. This encounter happens shortly after Ron’s long-delayed announcement to his dad on the phone that he has HIV. Dad pauses in his monologue about a sit-down lawnmower and says, “Oh. Yeah. Huh. How’d you get in that jackpot?” Then Ron’s sister, a manic “twig” with a meth habit, hears the news from Dad. Her convolutions of denial and rage close the tale with a scene of spectacular street theatre.

So you’ll laugh, and then you may cry, but Kearney’s take is that there’s a mix of both in any extreme human moment: an emotional double helix. I smiled and cringed at his array of meltdowns and household bedlams and macabre slapstick: a woman blogging about her pedophile ex-hubby, her alcoholism, her breast cancer; a sniping gay couple enduring a double-mammy Mother’s Day celebration; a star student who drops out to work in a dance company, falls on his head, then emerges from a coma to launch a career in cosmetics and witchcraft at Shoppers Drug Mart.

Kearney’s characters are the kind you encounter in real life and gawk at with secret incredulity — their body quirks, their questionable clothes, their complete failure to see their own behavioural atrocities. Your judgment may be fair and accurate or just plain mean, and Kearney gets that. His invented people seem as believable or unbelievable as the ones you meet on streetcars, in bars, at friends’ parties, or in your own family trenches.

If I have a largish quibble, it’s about the follow-through. Many of the stories ramble on repetitively, filled with activity but short on development, as if running on first-draft impulse. Often the endings feel more like random stops, cutting off events as they seem to be gathering toward something more complicated, more rewarding. My dark-tinged delight in the opening stories — the sense of being pulled happily, helplessly, into a unique world — faded as the collection progressed. That said, I would not miss anything yet to burst from Greg Kearney’s capricious mind.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra