The first time I meet Janine Fuller she is sitting quietly in a corner of her living room, listening to board members from Vancouver’s Queer Arts Festival review their work, go over budgets, and discuss upcoming events.

Her few interjections are mainly to ensure that various local artists are acknowledged for their contributions and work.

A few weeks later we sit down for our first interview, where she mostly deflects questions about her own contributions, and instead praises her coworkers at Little Sister’s, Vancouver’s pioneering gay and lesbian bookstore, which she managed for 25 years. She speaks highly of her friends and family, and of her partner, Julie Stines. When asked about her favourite memories from her decades of contributions to Vancouver’s queer community, she talks at length about her late employer, Little Sister’s co-owner Jim Deva, participating in the Pride parade.

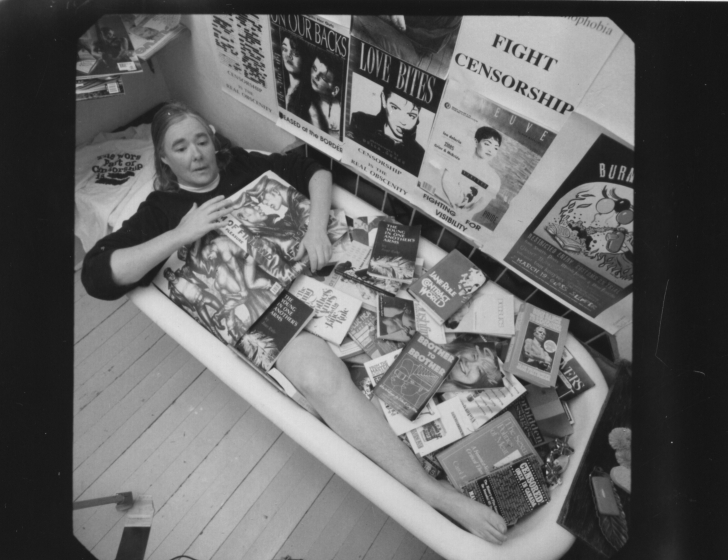

But Fuller is a force to be reckoned with in her own right. Best known as an anti-censorship activist, she worked tirelessly for decades at Little Sister’s, as it challenged Canada Customs for targeting its shipments of gay and lesbian books.

Her friends and her partner describe her warmly as a hard-working, dedicated, loving, open-minded and generous person.

In addition to her activism, Fuller is an author, playwright, and performance artist. Before moving to Vancouver in 1989, she wrote and starred in a comedic one-woman play in Toronto called Big Women Make Their Own Clothes.

She has received numerous awards for her community work and achievements, including the inaugural Reg Robson Award from the BC Civil Liberties Association in 1997, the Freedom to Read Award from the Writers’ Union of Canada in 2002, and an honourary Doctor of Laws from Simon Fraser University in 2004.

She has also been inducted into the Q Hall of Fame Canada, and the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives National Portrait Collection. Most recently, she received the Mayor’s Achievement Award as part of the 2016 Vancouver Awards of Excellence, which “recognizes remarkable dedication to improving the quality of life for the citizens of Vancouver.”

An hour into our interview she pauses to point out the silence.

Have you noticed the phone hasn’t rung once since you’ve been here, she asks me.

She says that’s often the reality for people who are sick — others just don’t know what to say.

After 25 years at the till, Fuller left the store in the fall of 2015 to tend to her health.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra