“He was out and proud for decades, way before it was easy,” says Jack Hallam’s longtime friend, Gordon Handford. “Jack was right there on the barricades.”

Hallam died Nov 14, 2015, on Salt Spring Island, BC, where he had made his home for more than two decades. He was 87.

His friends remember him as a thoughtful, kind and vivacious man with a good-naturedly crusty edge to him.

“Jack twinkled,” Handford tells Daily Xtra. “Jack was involved and an incredibly vivacious gay man.”

Passionate about gay rights, animal rights and human rights, Hallam founded Salt Spring Island’s gay group, GLOSSI, and donated money to several groups locally and across Canada, in part to endow bursaries and scholarships.

“He was extraordinarily bright and incredibly scrupulous in terms of ethics and meaning what he said and saying what he meant,” Handford says. “He had a bit of crustiness to him and he didn’t suffer fools gladly.”

Hallam came out in his 20s in 1970s’ Toronto, at a time when police still arrested gay men (and, in 1981, infamously raided the city’s gay bathhouses). Hallam himself was arrested in 1970 after police entrapped him in a sting operation in a washroom at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. He was charged with “counselling to commit an indecent act” with an undercover police officer.

Hallam enjoyed telling the story of his trial, and especially why he was acquitted. As he wrote in a letter to Daily Xtra in 2011: “The arresting cops testified at the trial that I was circumcised. When 8 x 10 glossy photos of my uncut dick were shown to the 12-man jury, I had to be acquitted.”

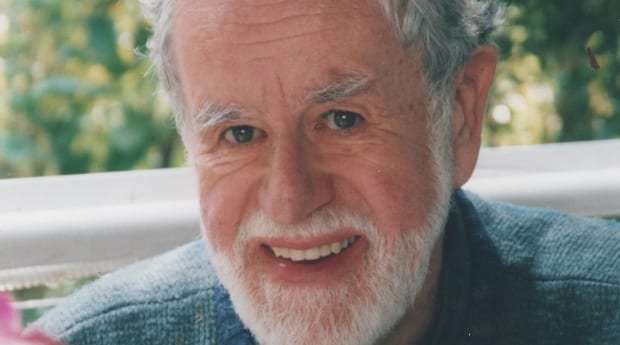

(Having inherited some money from his sister in 2006, Jack Hallam, above, donated it to several organizations and endowed scholarships for students in BC and Ontario./Courtesy of Gordon Handford)

Toronto activist Gerald Hannon shared Hallam’s two-bedroom apartment in the 1970s, and remained friends with him ever since. He echoes Handford’s words.

“He was kind of like a model of what can happen when you have the right political ideals,” Hannon says. “He was the classic grouch . . . but it was mostly an act.”

Hallam was born in June 1928, having been conceived, he writes in his self-penned obituary, “at his grandmother’s Haliburton, Ontario cottage on the Thanksgiving weekend of 1927, the only place where his unacknowledged lesbian mother and father retired to the bedroom at the same time.”

He graduated in biology from the University of Toronto in 1952, then obtained a master’s degree and taught in a grammar school in London, England, and in high schools in Toronto and Montreal. He later obtained a PhD in zoology.

“Reportedly ‘saved’ at Eglinton Baptist Tabernacle in Toronto at age 14, by age 20 in university he was enlightened and became a life-long atheist,” Hallam writes in his obituary, published in the Globe and Mail on Nov 28. “Jack was well into his 20s when he finally accepted being gay.”

“I think he’ll be remembered as the caterpillar that turned into a butterfly late in life,” Hannon says.

“He was a scientist and a rationalist,” Hannon says. Of Hallam’s atheism, “He didn’t push it.”

In addition to his years as a teacher, Hallam also owned a part-time antique business and a pet shop in Ontario, and he opened a small art gallery and a bed and breakfast on Salt Spring Island.

“In mid-2006, he received a substantial bequest from his sister and was able to indulge his philanthropy,” Hallam writes in his obituary.

He used part of the money to establish a fund with the Salt Spring Island Foundation on behalf of GLOSSI, and endowed two annual human rights awards for Grade 12 students at Gulf Islands secondary school.

He also endowed two entrance bursaries for First Nation students at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, and donated $100,000 to graduate and undergraduate scholarships at the Mark S Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at his alma mater, the University of Toronto.

Hallam directed his ashes, mixed with those of his beloved dog Blaze, and three of his cats, Snoopy, Snugger and Bart, “be scattered within the 19 Cusheon Creek acres that his and hundreds of other’s donations to The Land Conservancy, helped save from development” on Salt Spring Island.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra