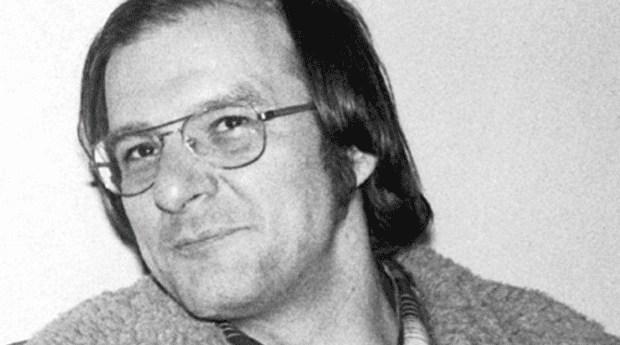

Claude Vivier is one of only a few internationally renowned classical composers from Canada. Now, 30 years after his death, he’s getting his first biography. And what a biography it is: Irish musicologist Bob Gilmore left no stone — and no score — unturned in the pioneering Claude Vivier: A Composer’s Life, which draws Vivier against the backgrounds of Canadian culture, the European flower-power and sexual revolutions, post–World War II avant-garde music, and Asian musical heritage.

In today’s Canada, Vivier is infrequently performed outside contemporary music circles, and most of us will have heard only of the tragic way his life was cut short (he was murdered by a man he had met at a gay bar and invited to his apartment). Gilmore’s book aims to redress this and is sure to revive interest in a unique figure of 20th-century Canadian cultural life.

Xtra: Vivier is really vivid in your book; you convey his personality, his manners, quirks, even his smell. How difficult was this task?

Bob Gilmore: It’s an important part of biography to create not just a narrative of someone’s life, but also some sense of their character and personality, what it must have been like to know this person. Vivier was an extraordinary figure, and I talked with many of his friends about his character and temperament and his rather . . . exuberant manner, let’s say. It was important to recreate a real human being: what kind of a man he was as well as what kind of artist.

Did you face any reluctance from any quarters?

There was some reluctance among what I would call his gay circle to talk much about that side of him. And I don’t really know why; I suppose it’s a natural resistance on the part of the people concerned. But I had to do a bit of digging. It was a very important part of him as a person, and it does relate in a certain sense to his art, too. I found some people reluctant, and I had to draw them out a bit, until they realized that I wasn’t trying to write some kind of prurient biography, that this was a serious study in which I wanted to deal with the whole personality. I didn’t want to write a sort of airbrushed, cleaned-up, sanitized version of his life, so that took a little bit of digging.

Some of his girlfriends spoke with you but none of his boyfriends. And his relationship with the writer Christopher Coe you essentially had to infer from Coe’s fiction.

Coe is, of course, long dead, so that’s all we have. Vivier’s life was rather solitary; there weren’t really many what we’d consider real relationships. There’s not very much to go on in that sense. The question was whether he was unhappy about that and whether he was even looking to have a stable relationship. In some sense, the music always came first for him. But he did die very young. Who knows what would have happened if he got to live longer; maybe he would have ended up happily married.

I really appreciate how you cut through the mystifications about his death and called it for what it was: a brutal case of gaybashing.

As you’ll see in that final chapter, there are two main theories about his death. One is that he was on some sort of self-destructive course, but that’s not how I feel. The other possibility is that it was a tragic accident. That’s closer to what I think, but I would not entirely agree. It was a hate crime. The guy who killed him killed two other homosexual men and was on the run from the police. It’s unspeakably tragic. In the book I wanted to lay out what I believed to be the case. It was very much a targeted hate crime against a homosexual man.

It seems that all through Vivier’s life money was short, even when he became an established composer.

He took a courageous step of living as a freelance composer, something that was very hard to do in his era, as it is now. He was surviving on grants and commissions and never had much money. The family that had adopted him were poor, so no financial help came from that side. Near the end of his life he got this considerable Canada Council grant to support his studies in Paris — not exactly comfortable, but he had enough to get by on. But he was only there for nine months before he was murdered.

I gather from your book that he belonged to the generation of composers who rebelled against the post-war European music avant-garde and people like Stockhausen. But Vivier in particular also remained very loyal to it?

He was a Stockhausen devotee, let’s say. He idolized Stockhausen in a way and thought him a great musical genius: Vivier learned a lot from his teachings. But in the course of the 1970s, around the time of his visit to Asia, for example, you see his music beginning to change. And the music changed in a direction rather different from Stockhausen’s. In that sense, he had a lot in common with his composer peers and fellow students. But in Vivier’s case, his turning away from the official avant-garde took the form of enlarging the scope of his music and dealing with new subject matters. Even till the end, he used some compositional techniques that he would have gotten from Stockhausen. In a sense, there was never really a rebellion — more a process of accumulation of new things.

Any idea why he wasn’t interested in the text so much as a composer, even though he was a voracious reader?

There’s his collaboration with Claude Chamberland for Prologue for Marco Polo, but that’s the only real exception to the case. He felt he could work better with his own texts, whether they’re in French or English or the invented language that he uses. At the time of the Prologue he says something to the effect that “I thought that for once in my life I should use a real text.” But part of his creativity was this interesting capacity to make up words, make up syllables that are meaningless in the conventional language but that nonetheless worked for him at the level of signs and gestures.

Is it fair to say that he was one of the most autobiographical composers of the 20th century — that all his compositions are, in a way, about him?

I would say that, yes. There’s a strong autobiographical component to all the pieces that he wrote, and even those that are seemingly on other matters turn out on closer examination to be more personal. There’s this piece called Greeting Music, for example, an instrumental quintet, no text, but one of his friends explained to me that the title Greeting Music was meant by Vivier as a greeting to the homeless people on the streets of Montreal, which is a group of people he was always interested in and could identify with to some extent. And there are the pieces like Paramirabo or Et je reverrai cette ville étrange, which are purely instrumental but that come out of Vivier’s obsession with travel and the allure of distant lands.

What is his status right now internationally? Is he being performed, known by the concert-going public?

I would say the knowledge of his work is growing all the time. Several factors led to that: one, its being taken up by a major publisher in 2005, Boosey & Hawkes. The availability of scores and materials has boosted performances, no question about that. There are also a number of young composers who are interested in his work, in what he did technically, in terms of his musical language. As for how much he’s known to the public, contemporary music of this sort will never draw huge crowds, but the performances are increasing, and there’s more and more sense that this was a major figure and a very original one. There’s nobody who, like Vivier, really manages to combine this extremely strong emotional content — lots of his work is overwhelmingly emotional — with the compositional rigor of the sort that he was able to employ. His work will continue to be better known as the years go by.

And a lot of his pieces simply call for a staging.

Staging is expensive, and there haven’t been many staged Vivier works. But Kopernikus, a small opera for seven singers and seven players, gets done quite a lot. There was one production in Holland and one in Germany just in 2014. His biggest work, the opera Prologue pour un Marco Polo, was done once in Holland. There’s so much richness in that piece and so many fantastic dramatic possibilities.

Postscript: I spoke with Bob Gilmore over Skype on Dec 27, 2014. He was a generous and thoughtful interlocutor, and I would never have guessed that he was seriously ill at the time. In the early days of the new year I was astonished to learn of his death, on Jan 2, and soon after received an email confirming this from his partner, violist Elisabeth Smalt. Bob Gilmore died of cancer at the age of 53. This was his last interview.

Claude Vivier: A Composer’s Life is published by University of Rochester Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra