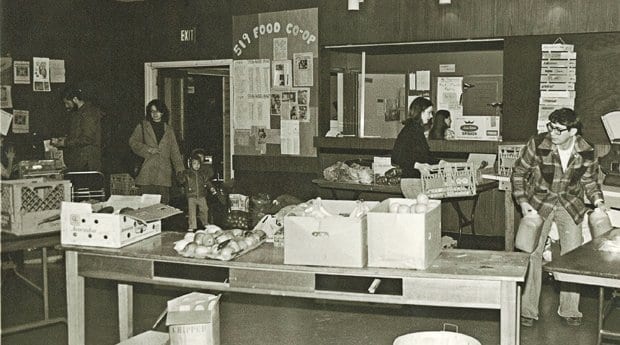

Many community members first got involved with The 519 through its food co-op.

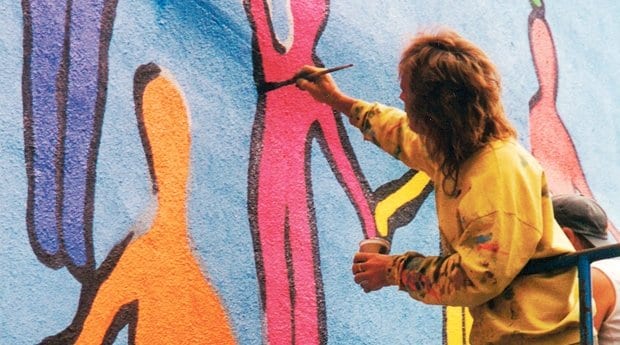

Volunteers prepare to paint the first of many murals that eventually grace the side of The 519.

A new mural is painted over an old mural.

The completed mural puts a rainbow over the community on a cloudy day.

A mourner at the AIDS memorial.

BIRTH OF A QUEER SPACE

The 519 was originally a hall for the Granite Club, but by the 1970s it had become a dilapidated hangout for the 48th Highlanders, and the city condemned it.

Kyle Rae (board member, 1981–86; executive director, 1987–91; city councillor, 1991–2010): The city was about to destroy it, and the neighbourhood said, “Hold on, we need a place for meetings, a place for services.” So they give it to the community and set up a very special way of operating. At first the seniors dominated, but in 1976/77, an application comes from a group called Gay Youth Toronto. It was young gay people trying to get use of the building, and in the end they do get in, which creates the tension with the seniors.

Then in ’78, the big kerfuffle with [anti-gay activist] Anita Bryant occurs. That is when the seniors walk away. When everyone organizes for Anita Bryant’s event up in North York, the buses load people up at The 519. They have effigies of Anita Bryant and somebody burns the effigy and puts the torch in her crotch. The seniors go nuts because Anita Bryant was Miss USA in 1960.

INNOVATIVE FUNDING

Many say the key innovation of The 519 was that the city owned the building and paid for its upkeep and core staff, but all programming was made and funded by the community.

Helen Rykens (519 staffer, 1983–2013): It’s way more efficient than the city-controlled system. We wouldn’t have been successful without that model.

Kyle Rae: Every year we’d go in and defend our budget and say there’s an increase in staffing or we need new computers, and the city would determine, is this in the operating budget or the programming budget? For example, there was a battle in 1986. We bought those new steelcase chairs, which are still there. We had a battle with the budget committee: is that a capital expense or a programming expense? ’Cause it’s for the people to sit during your programs.

Helen Rykens: You get an active board in the community and they don’t want that building to be empty. You have to respond to the people who live in the neighbourhood because they’re going to elect the board.

Kyle Rae: The gay groups didn’t get funding. They were all self-actualized. That was the quintessential essence of The 519 back in the ’70s and ’80s.

Chris Phibbs (programming director, 1987–91): People would apply for space, and then we would map it out to see whether we could squeeze them in — does it respond to a need that the community has expressed? Whatever they do in that room is what they do, and they charge two bucks for coffee every week in order to make money.

David Snoddy (former board member): The drag community and the bars were always an active part of supporting The 519. If you were a new group, you’d partner with a local business and a drag queen who’d get behind it or someone who had some sway within the community.

Philip Hare (519 bookkeeper, 1988–91): My first Pride Day ever, it was the first Pride focused on The 519. There used to be an auction in the park [to fundraise for The 519], and Jack Layton was the auctioneer. I thought he was drop-dead gorgeous and I wanted to meet him, and I was crushed when I learned he was straight. But he was so sweet.

GOING THROUGH THE DOORS

Kyle Rae: Kids were often drifting to Toronto. There were far more street kids then than there are today. You’d have kids who would be working the street. They would go to The 519. There was a real mix of kids.

Philip Hare: I was aware of The 519 for years before I actually ventured into it. I knew about LGYT [Lesbian and Gay Youth Toronto], but I wasn’t brave enough to venture in the doors. I’d pick up brochures about groups that were meeting there. I just knew it was a great place to get information, and at that point in my life that was enough, just to be in a gay place. I’d just go in, and there’s something reassuring about being in a place that’s so gay-friendly, even though I wasn’t officially out at the time.

In 1988 they advertised a job for bookkeeper, which I had no experience at whatsoever, but I applied because I had just come out and I really wanted to work there.

For 30 years, Helen Rykens worked at The 519, retiring as manager of public access and facility services in July 2013. She was a rare constant in the fast-changing space.

Helen Rykens: I moved to Toronto probably ’78, ’79, and I lived in one of those apartment buildings on Jarvis Street, and I felt lost in a large city. I walked around and found Church Street, and there was The 519 Community Centre. There was a food co-op there that I joined. I started there as a volunteer.

Kyle Rae: She was absolutely amazing at welcoming the people who were in tears from losing their jobs for coming out or losing their parents because they’d come out.

Kristyn Wong-Tam (city councillor): Helen was one of the first faces I met when I walked through the door, shaking and trembling as a young teenager coming out to LGYT. I didn’t know where I was going or what I was looking for, and she just looked at me and said, “Up the stairs.”

Kyle Rae: Helen knew who belonged here. With LGYT there were people who would hang out who shouldn’t be hanging around LGYT, and she knew who shouldn’t be here. Helen knew how to keep the building safe, keep the building’s integrity, keep the building working.

A QUEER CENTRE?

Officially, The 519 has never been a queer centre — the city authorized it to serve the neighbourhood bounded by Bloor, Bay, Gerrard and Parliament streets. It has always served a diverse group of communities.

Kyle Rae: It was by accident, by creativity, it turned into the gay community centre, but I fought that because once it becomes that, [other] people will feel it’s not part of their community. It’s great that queers from Scarborough came in, and it’s sad because you’re not going to get anywhere with the mayor of Scarborough or Mel [Lastman] in North York. Being a community centre gave it legitimacy.

Chris Phibbs: There was a program every Friday night for developmentally disabled adults. It was also user-run. The users would DJ, they would collect the tickets, run the bar, select a theme, do the decorating. It was their only day out of their group home.

Kyle Rae: The queer community had no idea it was there. They were at the bars on Friday nights.

Chris Phibbs: There was also a homeless drop-in that would happen every Sunday morning. There’d be clothes available for them; there’d be a hot meal.

A BASE FOR THE COMMUNITY

Still, The 519 has been a home to dozens of queer community groups who needed a safe, public, welcoming space to hold group meetings and organize.

Kyle Rae: I was coordinating Pride; the gay dance committee met there, and all the gay community organizations who had weekly or monthly meetings met there. And if you had a big public meeting, you’d use the auditorium.

Chris Phibbs: Notso Amazon baseball league met there. That was the reason I started going.

Kyle Rae: Political activism grew out of The 519 because of the queer issues.

Helen Rykens: We had a thing in the space-use policy where advocacy was encouraged. Because we were able to provide space for free, those groups were able to meet more easily.

Once they’d felt they’d dealt with the issues in their own communities, those groups would tend to disband. The Polish Gays and Lesbians, when they started — it was very funny — the leader of the group said, “I’m very sorry, but I think some older Polish ladies will be protesting outside the building. Do we have to cancel the meeting?” And I said, “Absolutely not!” Eventually they were accepted in the Polish-Canadian umbrella organization. That’s the sort of thing that could happen in The 519.

David Snoddy: Programming for gay people focused on coming out and integrating to the community because there weren’t supports.

Helen Rykens: I thought it was really important to make space available for people who needed the room urgently, like if someone had had a bashing and wanted to have a community meeting. No matter how busy we got, I kept the flexibility in the schedule.

A BRIDGE TO THE POLICE

Kyle Rae: In 1991, I got queerbashed twice on Church Street, so I contacted 52 Division and said, “Where are the stats? Is this growing?” And they said, “There are no stats because no one is telling us about the gaybashing.”

So I started this phone line, this bashing line, so people could record their being bashed and they could submit it anonymously, or they could submit it with their name and address hoping police would respond. Every day we would fax them to 52 Division.

Chris Phibbs: It was just an answering machine in the beginning. We’d be sending it and the police were like, “None of these people are talking to us,” and we started forging a real relationship with 52 Division. In the end, we started doing fundraisers to buy bicycles for the police so they could do bike patrols. Nine bikes we bought — 10 years after they turned our community upside down!

David Snoddy: Some of the community members were invited to go to the police training camp at CO Bick [police college] to provide some awareness. I became one of the volunteer community speakers. Toronto took it quite seriously at that time. That was a first to be done by any police service.

It started to show that with a little work with communities and partner agencies, you could build bridges with how the public views the police and how the police deal with problems of community safety.

A NEW NAME

It’s officially The 519 Church Street Community Centre, but almost no one calls it that today.

Kyle Rae: When I became ED, I went through a rebranding. We got Philip Hare to do a new design, and the letterhead said “The 519,” right in the corner. It became The 519.

Philip Hare: It was just kind of a no-brainer. That’s what everybody was calling it. The logo that I did was just “519” in sort of a loose, hand-drawn style with “The” written above it. This is 1988, so the logo I submitted was hand-drawn. The original drawing was just marker on paper, old school.

We also had a sort of informal logo that we put on T-shirts for fundraising that was a dancing version of the building. Chris Phibbs hated it, but Kyle loved it. The original building had an arch at the front that became the crotch, and I added feet and little Disney gloves and a face.

THE AIDS CRISIS

Chris Phibbs: The AIDS memorial became a program of The 519 that did have some staff involvement. We helped do the design competition and the call for submissions and the second call for submissions. There were a lot of angry artists because the first one didn’t demand that they have names on it.

Helen Rykens: A lot of the time when someone died, the funeral would take place somewhere else. The family would come down and a lot would be denied, and people from Toronto wouldn’t necessarily be invited. The idea was that people needed a place to grieve.

Chris Phibbs: There was some push-back, but the neighbour stuff was dealt with by having neighbourhood input early on and being careful about where it was placed and how it would grow, because the worry was it would just grow and grow and grow.

Helen Rykens: Years later, parents would come in and say, “Someone told me my son’s name is on the memorial. Did you know him? Could you tell me about him?” I would look in my records and find out who put in the name and try to get them in touch, and if not, I would take them out to the memorial and show them.

OPPOSITION

Despite The 519’s community involvement and autonomous governance, it faced occasional opposition from neighbours and even city hall.

LE Wakelin (board member, 1975–86): We had challenges with one of the mayors, a female, who seemed to think that we weren’t worth the money that they were giving for core staffing. We did about a six-month survey of who was coming, what they were doing, what the volunteers were doing, and discovered that for every dollar the city was spending, they were getting back $10 in volunteer time for people running programs.

Kyle Rae: In 1984, [then-councillor, future mayor] June Rowlands forced the city auditor to do a major audit of The 519, and the article in The Sun ended up saying something like, “It’s quirky, but it works.” We’d tried to get a new stove in the kitchen, and she did not believe they needed to have it. It wasn’t so much a queer issue, although she had a real problem with queer. She used this kitchen issue.

THE FUTURE

Kyle Rae: We were in a struggle and that struggle’s gone. There are struggles that are around the world that we should be involved in leading on and changing that experience. But the world has changed from when we were fighting the police, the province, the city.

Chris Phibbs: The hope is that it’s not necessary because we should be able to meet and get organized anywhere, and in most big cities that’s probably possible. But there was a time where that wasn’t possible. We could only do that in our living rooms or at The 519.

Helen Rykens: Pride Uganda is still meeting at The 519; the Queer Refugee Program still meets and is advocating for queer rights around the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra