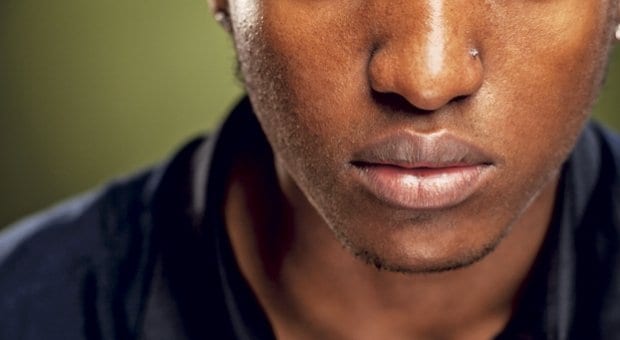

Michael Kivumbi (not his real name) didn’t get much sleep the night before his Jan 17 hearing at the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB).

“I was really nervous; it’s really psychological. You are not guaranteed anything. You have to pour out your heart to someone who has never been in your shoes and who you wouldn’t want to be in your shoes,” the tall, slightly built, 23-year-old gay man from Uganda quietly recollects. (He has asked Xtra to use a pseudonym for fear of future repercussions.)

Kivumbi’s hearing began around 8:45am. By 9:20, the IRB member had read and heard enough of his story to rule in his favour.

“I’m glad to have someone to understand me, just like the communities that have received me here. What can I say … the 17th at my hearing, it was just the icing on the cake, because I really don’t like going back to what happened to me.”

Kivumbi arrived here from Uganda in August, about four months before his country’s lawmakers passed a widely condemned but long-anticipated bill to further criminalize homosexuality.

Under pressure to reject the measure or give it his assent, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni says he intends to review the bill, which reportedly no longer includes the death penalty but still imposes a 14-year prison term for a first conviction and life imprisonment for the offence of “aggravated homosexuality.” It also criminalizes the “promotion” of homosexuality and promises to punish with prison time anyone who fails to report homosexual activities to police.

Museveni has called the bill “fascist” and objected to its passage by parliament without quorum, but he hasn’t ruled out approving it.

Kivumbi sees the bill as superfluous. In Uganda, people don’t need legal licence to be homophobic, he says.

Just weeks after Kivumbi arrived in Canada to pursue his studies at Simon Fraser University last fall, police paid his mother a visit at her Kampala home, he says. They told her they were looking for him because he has sex with men. He was not yet out to his mother.

Kivumbi, who was raised in a conservative Christian family, says he confessed to his mother when she called him.

“My mom, she got so angry, she insulted me. She told me she wished she had produced a dog. She told me she didn’t want to have anything to do with me, and she was going to tell the whole family so they would disown me,” he says. “Really, when I first heard that, I thought …”

Kivumbi can’t finish his sentence. He’s at a loss to describe how he felt hearing those words uttered from thousands of miles away but loud and clear in his ear.

Still, his mother’s reaction confirmed the fears he had had all along while he was still under her roof in Uganda.

“Definitely, there was no way I was ever going to make my status known to them. You live a discreet lifestyle. Even in your own family, you aren’t going to open up to anyone. You aren’t going to ask anyone for advice or to guide you.”

Aware of the anti-gay views of various pastors, he didn’t open up to anyone at church, either, in case he was ostracized. He has heard the fire-and-brimstone sermons from anti-gay pastors like Martin Ssempa.

“It just makes you feel lonely; it just presents you like a total outcast,” he says.

Kivumbi also kept his own counsel at the Christian and Islamic schools he attended, instinctively feeling that it would be too risky to reveal his sexuality. But, he says, his fondness for tight-fitting tank tops and fitted pants attracted his schoolmates’ ridicule.

“The way I dressed caused me problems at times. They would make fun of me. They would say I look feminine and make those sorts of jokes, saying that I’m trying to attract boys. There was that category that always used to point fingers at me.”

Even though fellow students were speculating about his sexual orientation, Kivumbi says, he was never physically harassed at school. His first encounter with violence occurred after he graduated in 2010.

Seeking privacy, he and his boyfriend, who would usually meet at their respective homes, decided to go to a Kampala park, where they began making out. Kivumbi says they were interrupted by the sound of footsteps. He looked around and saw four young men, three of whom he recognized from school.

“I heard them shouting derogatory terms. They were saying, ‘We should kill them. We should beat them and hand them to the police.’”

He says the situation then turned violent. “They kept punching us. They were four; we were two. My boyfriend was a little bit stronger than me, and he tried to resist, but it went on and on, back and forth.

“They had sticks and one had a bucket, and he kept hitting us with all these objects,” he says. “All I remember is I kept losing consciousness.”

When it was all over, Kivumbi says, he tried to stand up but couldn’t put any weight on his right foot. He says his boyfriend, who sustained welts and bruises on his body from the attack, had to help him to a taxi.

At the hospital, Kivumbi, who found out that he had a fractured tibia and now has plates in his leg, kept the story about the attack simple, leaving out the reason for the assault for fear of facing further discrimination.

He didn’t bother reporting the attack to the police. “They don’t support gay people. What was I going to say happened?” Neither did he give his mother a full airing of how he was injured, telling her only that he was jumped while walking in the street.

While he doesn’t know for sure how police found out about his sexuality, he suspects that his attackers in the park may have spoken to authorities.

He says the attack buttressed his resolve to leave Uganda to pursue higher education sooner rather than later. “I was so traumatized. It pushed me to apply more quickly.”

With the police inquiries and his family’s rejection, he doesn’t see himself returning to Uganda.

“I’m trying to pick myself up now,” he says.

Kivumbi is trying to build a community of support. He volunteers with the Health Initiative for Men (HIM) and is also involved with Qmunity.

“I met good people, counsellors at Qmunity — people who understand me and showed me people whose stories are not exactly like mine, but people who have gone through the same kind of problem, where they had to leave their home country for such reasons.”

Kivumbi also says that prayer has brought comfort. He has been attending St Andrew’s-Wesley Church, where he met Reverend Dan Chambers, minister of congregational life.

“He told me at the end of the day, a church should be welcoming, irrespective of someone’s sexual orientation,” Kivumbi says.

The service format at St Andrew’s-Wesley is the same as that in Uganda, he notes, but it’s different because he feels welcome. Chambers says Kivumbi has been at services almost every Sunday since September.

“I empathized with his family situation — recognizing the cultural differences — how incredibly difficult it would be to be ostracized from your family, from your society, from basically everything you have known,” Chambers says. “I’m glad that the church can be there for him, for people who are in his situation.”

Being heterosexual, bisexual or homosexual is “just the way you come into the world,” Chambers says. “It’s not something to be fixed. It’s something to be lived, and hopefully lived with much love and joy.”

While Kivumbi’s refugee hearing understandably filled him with uncertainty and despair, Chambers says, the asylum he’s now been granted is reason for optimism. “He does seem to be in a better, stronger place.”

“It was really fast; we were there for less than an hour,” says lawyer Kirk Olearnek, who represented Kivumbi at his refugee hearing.

“When people are from countries with atrocious human-rights records, basically, it’s all about credibility,” Olearnek says. “There’s more scrutinizing of ‘Are you really gay?’ Once they get over that threshold, usually everything just falls into place.”

Kivumbi did all the heavy lifting, says Olearnek, who had his submissions “ready to go” but was told by the IRB member early on that they weren’t needed — a sign that things would go Kivumbi’s way.

“That often happens with gay clients, because the member can see the country evidence,” Olearnek says. He says the board member noted the Dec 20 passage of Uganda’s anti-gay bill as a development that threatens to exacerbate an already-serious situation.

Kivumbi still can’t believe that his request for asylum was granted. “Even now I have not woken up from the dream; I haven’t yet faced the reality,” he says.

For now, he doesn’t want to focus on the evolving saga of his home country’s anti-gay bill or on what Museveni will or will not do about it. He would rather focus on the new life that he gets to build here.

“I’m looking at discovering myself … as a person who has rights, as a person who can live with dignity as a gay man.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra