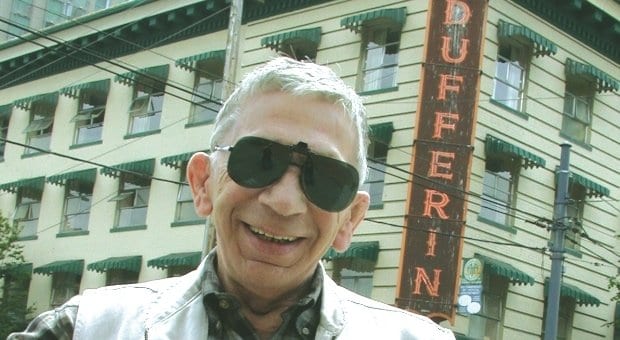

Cary Grant, former manager of the Dufferin pub and a supportive father figure to many, died after a lengthy illness Dec 20. He was 74 years old.

Born in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, on March 7, 1939, Grant was the only child of Edward and Hazel Grant. Predeceased by both parents, he is survived by his partner of 32 years, Jerry Hatchard.

Hatchard could not be reached for comment, but longtime friends are remembering Grant as a selfless, kind, down-to-earth and generous man.

“When he was managing the bar he was one of the gang, and we had a lot of fun with him,” says Earnie Doyle, a regular former patron of the Dufferin.

Grant managed the popular gay bar, which sat at the corner of Seymour and Smithe streets, on and off for at least a decade. The Dufferin became an important place for Grant and a host of hustlers, go-go dancers, drag queens and patrons who regularly congregated over cheap pints, raunchy jokes, campy entertainment and infectious laughter.

Grant made the edgy, gritty, dimly lit tavern a welcoming space for all genders, sexual orientations and classes. It was a place where patrons celebrated, mourned, hooked up, broke up and built lasting friendships.

“You really got a full cross-section of everybody in there,” says former Dufferin entertainer Paige Turner. “I spent so much time there that it felt like home. It was my living room.”

“It’s got a lot of charm,” Grant told Xtra in 2004. “That’s probably the last [gay bar] of its kind in North America. It’s a community centre. It’s a street bar. It caters to everybody, from the very rich to the very poor.”

“He was like a father,” Turner says. “If you had a problem you could go to him and he would stop and listen.”

“If the patrons drank too much, he would ask for their car keys and give them a room upstairs in the hotel. He wanted to make sure everyone was safe,” she adds.

Grant’s generosity was particularly appreciated during the holidays, when he would host an annual Christmas dinner for patrons, an act of kindness inspired by his own struggles with loneliness as a teen growing up in Toronto, Turner says. “Christmas was the time [Grant] found the loneliest, and he always wanted people to feel love and have a safe place to go.”

“I can paint a picture of this lonely gay kid in Toronto,” Grant told Xtra in 2004. “When Christmas Day came around, and, being a bit of a loner, I didn’t have places to go. At the Dufferin we just put the food out. We don’t announce it. We don’t advertise it. Just anyone that comes in has something to eat. I’ve always felt that people have to maintain their dignity and their pride.

“The Dufferin puts in some money; I put in some money,” he said. “We do it for the street people. There’s a lot of people in less fortunate circumstances, and rather than identify them, we just do it [the Christmas dinner] for everybody. They have to maintain their dignity.”

“He was a very honest, loving, trustworthy man and a true brother to me,” Byron Longclaws says.

Longclaws, former chief of the Greater Vancouver Native Cultural Society, chose Grant as his honorary chief in 1996. “I chose him because he was manager of the Dufferin and he helped promote and do shows for fundraising,” Longclaws says.

Grant hosted fundraising events weekly at the Dufferin and gave countless donations to community charities through the work of groups such as the Dogwood Monarchist Society, the House of Just Cuz and the Knights of Malta. “[Grant] was very openhearted to a lot of people in the community, not just the Native Society, but to all societies,” Longclaws says.

When the Dufferin changed ownership and eventually closed its doors in 2007, Grant was still on the frontlines, lobbying for the iconic gay pub. “He tried to hold on to [the Dufferin] as much as he could,” Turner says. “It was a huge battle for him. He really left his stamp on the bar. You could feel his spirit throughout it.”

“Once the Dufferin went, the whole feeling of community went,” Turner says quietly.

“After the Dufferin had closed, we had to realize that there wouldn’t be another place like it — and there will never be another man like Cary for the community,” Longclaws says.

“He was the Dufferin,” says Al Houston, who worked as a doorman at the bar. “He saw that I was struggling with personal issues and he offered me a job, and we became friends.”

“If he could help, he was there to help,” Houston says. “Cary was respected by many.”

When pressed to define Grant’s character in a few words, Turner falls silent.

“It’s really hard to put who Cary was into words,” she says softly. “He really believed in bringing the community together . . . He was an amazing person with a heart of gold.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra