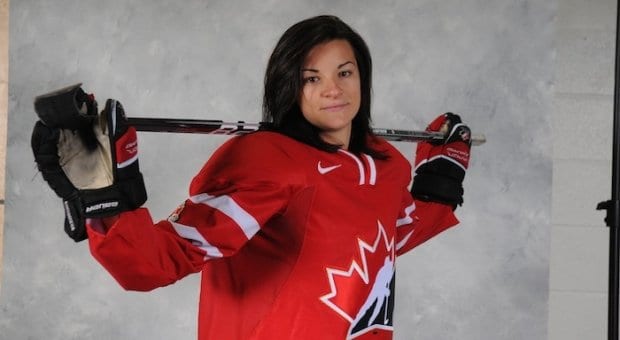

Having three surgeries in a few months would make for a tough recovery for anyone, but especially one who hoped to compete in international-level sports immediately afterward. But for hockey player Sarah Vaillancourt, it was simply something she had to do before saying goodbye to Team Canada after 10 years on the roster.

Vaillancourt, who is openly gay, is still a player on the Canadian Women’s Hockey League’s Montreal Stars. She’s emotional as she describes her recent parting with the national team but says it had to happen to preserve her body.

“After the 2010 Olympics, I went through three surgeries,” says Vaillancourt, whose injured hip led to two abdominal tears. “There were times that I didn’t know if I was going to skate again.

“I had not more than one month to recover and I went back. I wanted to play in the World Championships last April in Ottawa, but I knew I was going to retire.”

The team won a silver medal at that tournament, the latest of many to be festooned on the Sherbrooke, Quebec, resident during her career. Since 2003, when she joined the national team, it has earned two golds and five silver medals at the annual international tournament.

Vaillancourt also has two Olympic gold medals, from 2006 and 2010. Her current team, the Montreal Stars, won the league’s Clarkson Cup in 2011. According to Wikipedia, she is one of only four female players to earn gold in all three tournaments.

She considers her long tenure on the national team to be her greatest accomplishment, noting you don’t just make the team once and get a free pass for life. “You’re never sure to be on the team the following year,” she says. “Making it to the national team was my dream since I was 12.”

The thing about top-level athletes, the agile forward says, is that they’re always pushing themselves to the next goal. It’s a mentality that poses a unique challenge to team sports: managing a group of high achievers who all want to be the best.

“It becomes competitive,” says Vaillancourt, now a coach at a prep school on the Quebec-Vermont border. “The big challenge is to balance that because it’s about being the best team.”

The prep-school environment may seem like a strange place for a self-described “Quebec liberal girl,” but Vaillancourt got her first taste of the upper-crust education system when she was a teenager. Scouted by the Harvard Crimson while in high school, she was advised she’d have to learn English if she wanted to attend one of the world’s most prestigious anglophone universities. She sought out a prep school in Connecticut to finish her secondary education.

“It was not only the English that was a barrier. Prep school was a huge culture shock.”

But it paid off. Vaillancourt got into Harvard and added a top-tier psychology degree to her dauntingly long list of accomplishments. During her time at university she played on three teams at once — her school team, the under-22 Canadian team and the senior Canadian team — and still had to somehow stay on top of her schoolwork. On a typical day she’d wake up around 8am, go to school all day, go to practice for a few hours after school, eat dinner and then tuck into her studies and homework.

“There’s not one night I went to bed before 11 or 12,” she says. “I still can’t believe I went through it . . . but when you’re in the middle of it, you think being busy like that is normal, that it’s everyone’s everyday.”

She says her arrival at Harvard proved educational for those around her as well, as she was the only gay player on the team to speak openly about her love life.

“There were other gay girls on the team, but no one ever talked about it or went on about it,” she says. “I came in and was like, ‘I’m into girls,’ ‘I think this girl’s hot,’ and that’s just how it is. Some of the girls were traumatized, but now when we have reunions, we laugh about it.”

Although never one to hide who she is, Vaillancourt says she can understand why some gay athletes don’t speak openly about their sexuality.

“I think a lot of them don’t want to be labelled for their sexual orientation. They are fine with it, but they want to be labelled for the athlete they are,” she says, noting her take is a little different.

“Eventually it will be something you don’t have to mention or something you can say casually, but we have to pave the way.”

Read about Olympic-medal-winning soccer player Erin McLeod, who says she hopes to be a role model for young girls in sport, in “Leading by Example.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra