You’d think from the way political elites are behaving that we — the electorate — are the ones running the government, spending public money, smoking crack and skirting accountability.

Why else would our elected officials and their minions feel so free to invade our privacy, even as they steadfastly guard their own?

We are a public that is increasingly spied upon yet stonewalled and firewalled when we dare to ask questions.

A few cases in point.

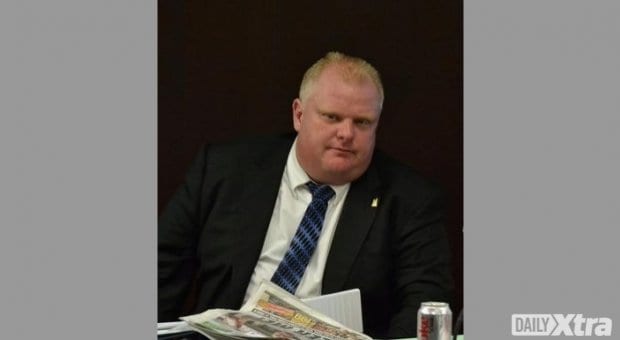

Toronto’s favourite train wreck, Rob “I ain’t goin’ nowhere” Ford, initially thought it sufficient — and only after so much stink had accumulated at his door — to muster a cynical, pro-forma apology for his “mistakes,” even as he played the outlaw gunslinger, daring the city’s sheriff, Bill Blair, to release the evidence.

Thumbing a hubristic nose at calls for his resignation, including from the city’s daily papers, Ford invited “anyone who wants to go” to go. He’d be “running this ship” — by himself if need be. (No word yet whether he’ll maintain that stance post-Nov 5 admission of having possibly smoked a little crack about a year ago.)

At the federal level, as a dazed and confused public tries to make sense of the degenerating “expenses scandal” and figure out who knew what when in the PMO food chain, reporters still encountered more closed doors than content at the Conservatives’ Calgary conference Nov 2.

“We’ve grown used to seeing prime ministers sealed inside an impenetrable bubble, but a whole party?” political observer Andrew Coyne said. “Creepy.”

For those who are salivating at the prospect that all this points inevitably to Stephen Harper’s undoing come next election, think again.

Politically, 2015 is a universe away. (For a template, see Christy Clark’s 2013 comeback from oblivion after more than a year of dire predictions of her electoral demise.)

Not to be outdone, the eavesdropping, peeping-Tom ways of the US have, curiously, aggrieved their European allies who indulge in the same antics, albeit in perhaps a less comprehensive, less technologically rich fashion.

The cross-Atlantic “you done us wrong” recriminations arising from the spook revelations are laughable for about five seconds. Many of us have suspected all along that 1984 had arrived; we just didn’t know the scope of it.

The technologically borderless landscape that we occupy — further laid bare by revelations from whistle blowers like Edward Snowden — has allowed us to glimpse the extent to which our elected officials feel entitled to watch, listen and hold us to account, while ducking our questions and telling us to “run along now” if we — quite legitimately — want to know what’s going on.

The question is, What can the average citizen do — or care to do — with what we now know, and want to know, in the face of the pervasiveness and perversion of the I-don’t-give-a-damn, who-the-hell-are-you-to-question-me attitudes of the people we elected?

“Speaking the truth is not a crime,” Snowden wrote in his rejected plea to American authorities for clemency.

I wish that were true, but in the current climate, the truth, far from setting him free, has consigned him to the indefinite status of global fugitive.

The information he has unleashed is a call to collective action beyond the international discussion that has been ignited.

We aren’t, nor can we all be, Edward Snowden.

By all means, continue to watch The Voice, and leer at the ab-fab Charlie Hunnam astride his hog on Sons of Anarchy, but we have our own undemocratic reality show that goes on for more than 45-minute time slots of escapism.

How long, and how much of it, are you willing to put up with, ignore or shrug off?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra