Jane lies in her bedroom reading a sexual-awareness book provided by Mami Joyce. Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

Adjen and two other trans sex workers who live at Mami Joyce’s chat with clients on mobile phone apps. Internet dating is becoming more and more common in the waria community, and profits can be 10 times more than the “street fee.” Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

Selvie, one of the tenants at Mami Joyce’s, helps a friend get dressed for work. Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

Adjen, 32, the oldest tenant at Mami Joyce’s house, outside her room. Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

The view of Jakarta’s business district from the second floor of Mami Joyce’s house, set in a low-rise maze behind Taman Lawang. Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

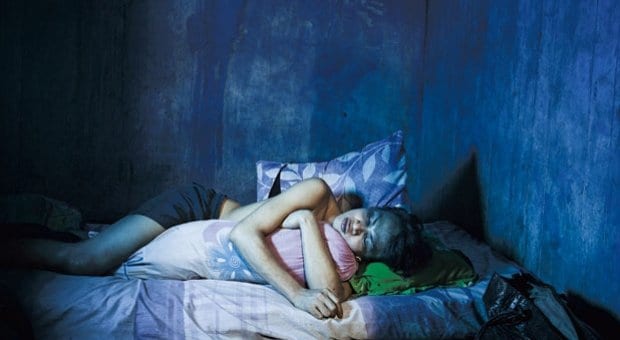

Selvie dozes off while watching TV in her cramped room. Credit: Giorgio Taraschi

The lights of Plaza Indonesia, with its swanky hotels, glitzy malls and iconic fountain roundabout, are only a few blocks to the north of Taman Lawang, a very different Jakarta neighbourhood. Come midnight in the leafy street that cuts into one of Jakarta’s wealthiest neighbourhoods, the dimly lit road belongs to young beauties who go by flashy names like Tiara, Marsha and Venus.

Customers stop their cars to haggle over the price of their company, and groups of giggling teenagers on scooters linger nearby to flirt with the idea of a tempting escape. For the beauties on the sidewalk are transgender sex workers, and Taman Lawang has long been synonymous with them.

For most of Indonesia’s trans sex workers, taking to the streets at night is a choice, but also, typically, it’s the result of having very few alternatives. The country, with its 245 million people, has the biggest Muslim population in the world. Yet most of the 86 percent of Indonesians who follow Islam live by moderate interpretations of the Koran, influenced by the archipelago’s animistic and Hindu traditions that predated Allah’s word here.

But religion has traditionally undermined acceptance of waria, a popular word combining the terms for woman (wanita) and man (pria) in Bahasa Indonesia, the country’s official language. Faith-based values have fostered discrimination in formal employment and in countless cases have moved ashamed parents to sever bonds with their transgender children, who are often kicked out of their families once they reach adulthood.

Many end up living under bridges. Those who don’t sell their bodies often find jobs at beauty salons and cheap food stalls, or they become buskers. Making ends meet is a monthly struggle: this helps to explain why almost all waria undergo hormone therapy and some have breast-enlargement injections, but a costly sex-change operation is extremely rare.

In the seedy-looking alleys near Sudirman Station, a low-rise maze at walking distance from Taman Lawang, “Mami” Joyce has recreated the closest possible thing to a family for 20 fellow trans sex workers who hail from all over Indonesia. An imposing 50-year-old, originally from Medan, whose manly daytime buzz cut is concealed by a blonde wig when she dresses up every night, Mami Joyce owns the premises of this rundown part-brothel, part-commune apartment whose two wooden floors come alive after dinner. That’s when its tenants start getting dolled up for a long shift in the streets. Each of them rents a room — nothing more than a dusty mattress on the floor and a cheap TV set — for $40 to $50 a month, roughly the equivalent of three nights’ work.

What the girls gain, other than proximity to Taman Lawang and their customers, is a sense of protection and community: both rare in a society that marginalizes them. The youngest is 18, the oldest 32. All have experienced HIV-related deaths among their peers and friends; according to a 2007 study, one third of trans people in Jakarta have contracted the virus. In Mami Joyce’s house, talking about AIDS and the suffering many have witnessed is a topic best left unspoken. Her mission is to instruct the 20 girls not to repeat the same mistakes. She drills into them the importance of using condoms — a practice many wealthy customers often shun, with offers of three times more money for the girls.

An outreach activist for Srikandi Sejati, an underfunded foundation that runs HIV programs for trans sex workers, Joyce insists each of her tenants go through a checkup every three months. “I’m like a mother, protecting my vulnerable children,” she admits while sitting beneath a poster of Marilyn Monroe that hangs over her leopard bed set.

Joyce isn’t the only prominent “Mami” active on the trans-rights front. Yulianus Rettoblaut, better known as “Mami Yuli,” recently made international news when she set up Indonesia’s first shelter for elderly trans people. It’s not an independent structure — she basically opened up her house in Depok, part of Jakarta’s huge southern outskirts, to fellow trans folks with nowhere to go. Still, her creation has rapidly attracted interest: “Since I opened it six months ago, I’ve got 800 people on my waiting list. So many people knock at my door for help, not necessarily transgender,” says Yuli, a former sex worker and a devout Catholic who five years ago became the first waria ever to graduate from an Islamic university in Indonesia.

Running the shelter with her own funds, partially aided by a network of local churches, Yuli dreams of gradually expanding her creation to host “all of Jakarta’s elderly waria,” with a new building in what is now an overgrown backyard. “Love is everything; I give all to all people,” she says.

Among the eight permanent “grannies” of the shelter — as they’re respectfully called by trans youth who regularly drop by to learn skills or simply to get a sense of community — Yoti Oktosea’s story is the most compelling, yet so typical of the painful difficulties waria have traditionally faced in Indonesia. Her family disowned Yoti, a stocky 69-year-old with drooping eyes and caring manners, when she was 18. She became a sex worker, then ended up — dressed as a man — working on cargo ships. “It has always been very hard to live as a transgender; it was a taboo that society didn’t want to touch,” she says. “Now parents are more accepting, and the media have a positive influence on tolerance.”

The past decade has seen signs of incremental changes in the country. Until two years ago, authorities officially deemed Indonesia’s estimated 35,000 trans people “mentally ill.” Now the government provides funds (albeit limited) to programs dedicated to them, including Mami Yuli’s. Some prominent waria have found domestic celebrity as singers or talk-show hosts: Dorce Gamalama, often called the “Indonesian Oprah,” was born biologically male.

In 2008, in Yogyakarta, a local activist transformed her hairdressing salon into an Islamic school for trans people. In 2006, the country saw its first Miss Waria beauty pageant. Mami Yuli herself is often invited to debates on TV; she, along with other activists, claims that the transgender population in Indonesia may amount to seven million. It’s an implausible figure, but so is the one provided by the government.

Trans people aren’t the only ones enjoying more visibility in Indonesia. The annual Q! Film Festival — dedicated to LGBT issues — has been a regular feature for the past decade in Jakarta. “More people in big Indonesian cities are getting increasingly comfortable in showing who they are in public — not only when they are in gay clubs,” explains Nico Novito, a young journalist who follows the latest trends in the community.

Social media (Indonesia has the highest per capita Twitter penetration in the world) is also playing a major role. The @nickynmita account, managed by two activists, aims to provide information on “how to live a happy and healthy life as LGBT.”

Jakarta has a small and discreet, yet lively, gay night scene. Hip clubs like Apollo, where upscale customers mingle, are famous for their colourful drag performances and go-go dancers. Yet discrimination is still widespread, and tolerance largely remains a matter of environment. Urban homosexuals may be coming out in increasing numbers, “but I’ve heard some stories where people can’t get jobs because their prospective employers know that they are gay,” Novito says.

Many waria have boyfriends, and an increasing number enter into relationships with married men — their wives often aware of the husbands’ double lives. But trans sex workers and gay people complain of being harassed regularly by the local police, who take on the role of defenders of public morality in a country where prostitution and homosexuality are both legal under the criminal code.

Nobody does this more than hard-liners from the FPI (Islamic Defenders Front), a notorious radical group that has recently embodied the resistance to progressive change in the archipelago. FPI militants periodically intimidate LGBT people, in several cases with death threats. A man dressed like a woman is haram (prohibited).

The group’s threat, and the reluctance of the authorities to crack down on it (to do so would risk their being accused of not defending Islam), has guaranteed the FPI a growing clout — many transgender groups have reluctantly cut down their social and educational events. In the past four years, the FPI forced the cancellation of the Miss Waria pageant and of a civil-rights training session for transsexual activists, where the “Defenders” showed up armed with sticks. Even the Q! Film Festival was partially disrupted in 2010 due to the FPI protests outside its venue.

Many Indonesian trans people remain practising Muslims, regularly visiting the local mosque — although they don’t dare dress as women when they pray. Being at the receiving end of Islamist threats is something that frustrates them, yet they can somehow take it in stride. “Some of my customers are FPI members,” boasts Intan, a 28-year-old sex worker, sipping coffee at Mami Yuli’s shelter.

Meanwhile, Darni, who earns her living as a singing hawker, reveals that her boyfriend recently joined the FPI. Everything is going well between them, she says; he regularly confides in her about the group’s activities. But with his fellow hard-liners, he keeps his relationship with a waria secret.

Despite this clandestine love story, however, all waria agree that a growing number of Indonesians identify as transgender. While overall welcomed as good news in a more open society, some sex workers joke that it can actually be a mixed fortune: “We used to be sought after by men,” chuckles Tommy, who at 51 now works in a hair salon after years on the streets at night. “Now there are so many waria that we almost have to pay young men to have sex with us!”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra