Credit: Trudie Lee

On the outskirts of Toronto’s Roncesvalles neighbourhood lies a repository of the artifacts of 25 years of unique and special genius. The site is the home and studio of puppeteer Ronnie Burkett and his Theatre of Marionettes.

The eponymous puppets for each Theatre of Marionettes production are designed and built there over the course of a year by Burkett and his assistants. The airy studio space houses a library of books on art history and contemporary performance. Various national and international awards line the walls, and intricate set maquettes sit on shelves. The basement, Burkett tells me, is the morgue, where retired puppets from decades of past productions rest in bags and boxes. This magical place has the feeling of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop as run by John Waters.

From his beginnings in Calgary — where he was part of the avant-garde milieu surrounding experimental company One Yellow Rabbit — Burkett garnered international acclaim for a trilogy of puppet works, which includes the Holocaust drama Tinka’s New Dress. In his book on the history of One Yellow Rabbit, Martin Morrow praises this phase of Burkett’s work for its drama and for moving audiences “to tears, as well as laughter.”

Burkett is now regarded as one of Canada’s most beloved theatrical exports, and his work routinely sets box office records whenever it returns home.

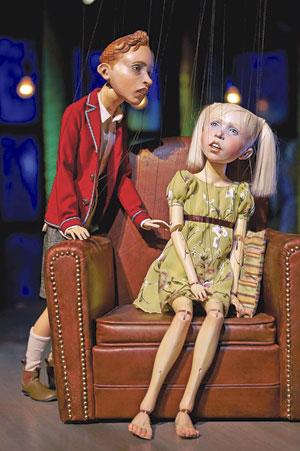

Burkett’s newest work, Penny Plain, arrives at Toronto’s Factory Theatre after successful runs in Edmonton and Vancouver. The piece, a co-commission of Edmonton’s Citadel Theatre and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, typifies Burkett’s ability to ring pathos from everyday situations. Black humour, irony, satire and a glorious camp sensibility are transmitted by more than 30 of his exquisite marionettes.

In the world of Penny Plain, society teeters on the brink of apocalypse. Penny is an elderly, blind shut-in who decides to ride out the end times in her living room, accompanied by her seemingly faithful dog. I ask Burkett about the eschatological aspect of Penny Plain.

“I was just thinking about what would end us,” he says. “Would it be the end of oil, would it be some crazy bird flu, would it be global warming? One day when I was writing, I had my penny-drop moment: it all happens at once, and that’s what happens in Penny Plain.”

The end of mankind is a potent image for Burkett, and he doesn’t see human extinction as altogether out of the question.

“I think I’m just kind of reminding people of what David Suzuki said once: the planet actually will survive, but we may not, so if we want to stay on the planet, we might need to adjust ourselves accordingly.”

Penny Plain broke box office records at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre. Burkett chalks up the warm reception to what he calls the perfect Burkett combo.

“It’s really fun and it’s really dark, and that seems to be what people like out of me: the mixture of dark and light, and this one’s got it.”

He adds, “I think this really is a great 25th-anniversary-season show. I wanted to prove to myself that the marionettes could carry the whole show, and I think the reaction has been strong because of it. People get sucked into that little world, and a minute gesture can floor them.”

It is fitting that Burkett refers to his storage space as the morgue. In order for puppets to die, they must have, at one point, lived. Through the caress of Burkett’s artistry, his inanimate objects seem more profoundly alive and strangely human than most flesh-and-blood performers. There is something almost alchemical about his work. An artist like him arrives once in a lifetime; do whatever you can to share in his madly wonderful world.

Below is a video interview with Burkett.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra