None on Record founder Selly Thiam.

Skye Tenivembo, a Zimbabwean refugee living in London. Tenivembo holds a photo of her grandmother.

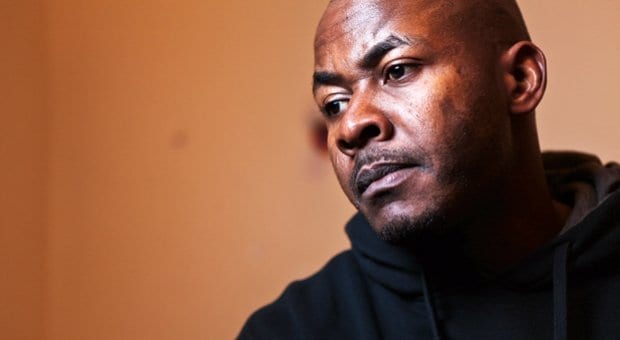

Uche Nnabuife, a gay Nigerian asylum-seeker living in London.

Bisi Alimi was forced to flee Nigeria in 2007 after he came out on national television. At the time, Nigeria’s president was claiming there were no gay people in the country and Alimi felt a moral obligation to correct the record. The message was not well received. Soon, Alimi faced verbal and physical harassment, culminating in a threat on his life. He left Nigeria for the United Kingdom to seek asylum, with the knowledge that he would probably never return to his homeland.

Alimi’s story is one of many included in None on Record, a digital media project that aims to document the experience of gay and lesbian Africans. Selly Thiam founded the group in 2006. At the time, there was scant media dialogue on queer issues in the African community, both on the continent and in the diaspora. Today the project is making a name for itself with a series of short documentaries that highlight the gay asylum experience.

“Stories affirm who you are,” Thiam says. “We keep hearing there are no gay people in Africa. Actually no, we exist. Here are our first-person narratives to prove it.”

Internationally, the situation for gay-identified persons is still dire. In 76 countries it remains illegal to engage in same-sex conduct. In Saudi Arabia, Mauritania, Sudan, Iran and Yemen, homosexuality is punishable by death. On the African continent, a series of high-profile laws criminalizing homosexuality received much media attention last year, most notably in Uganda. While countries like South Africa have taken progressive steps to ensure the health and safety of their gay citizens, in many African nations, gay-identified people live in a constant state of fear.

Thiam says the idea for None on Record came to her after the murder of FannyAnn Eddy, a prominent Sierra Leonean lesbian activist. Eddy was one of few speaking publicly about the plight of the gay community on the continent. She paid for it with her life. Thiam was working as a teacher in Chicago when she saw the newspaper headline announcing Eddy’s death. She was stunned. In the photo that accompanied the piece, Thiam saw fragments of herself.

“I am a West African lesbian living in diaspora,” Thiam says. “The lack of visibility and silence on LGBT issues in West Africa was having its own impact on me, but having it reflected back to me in this way was very traumatizing.”

The United Nations High Committee on Refugees estimates that at least 42 states have granted asylum to refugees on the basis of sexuality. But hard data on the number of asylum seekers is hard to find. Some nations grant asylum without a mandate to do so for the queer community, while others do not track their reasons for granting asylum. Internationally, LGBT asylum law is a recent addition to the dialogue on the rights of refugees. The United Nations 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees defines a refugee as someone who cannot remain in their home country “owing to well founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.” But it was only in 2008 that a guidance note was issued recommending that persecution on the basis of gender or sexual identity should be included in the understanding of the law.

In 2010, the United Nations finally released its first report on the state of human rights for gay and lesbian people. The report noted that “violence against LGBT persons tends to be especially vicious compared to other bias-motivated crimes” and cited a particularly high degree of cruelty and brutality administered during gay-motivated hate-crimes.

Thiam tried hard to shake the murder of FannyAnn Eddy, but she was haunted. Instead, she flew to conferences around the United States, desperate to find people who could help her understand her own place within the community. Soon, she found herself driving north to Canada with an audio recorder in hand. She had no idea what the end result of the interview would be, only that she wanted to learn more and that recording it was probably a good idea.

“This didn’t start as an oral history project,” she says. “It started as a question: what are the lived experiences of people who are LGBT or identify as queer in an African context.”

As it turned out, many of the people who could share these experiences lived in Canada. Thiam attributes this to more lenient immigration laws and a relative tolerance for the gay community. At the time, it was still illegal to immigrate to the United States as an HIV-positive person, and gay asylum cases were unheard of (Thiam notes that this has shifted under the Obama administration).

When she returned, an NPR producer friend asked to take a listen. The first interview was packaged and aired on national radio. For Thiam, this experience was a game changer. “I was really shocked that people were interested in hearing the story. And then, it gave me this idea, that there’s probably more people out there who want to share their story. There are people who want to listen to it. And I should be recording it and sharing it.”

Thiam started collecting stories. At first it was 10 a year, but then people started contacting her, asking her to record their stories. An audio archive soon blossomed.

Like so much of the None on Record project, the realization of video came almost by accident. Thiam was invited to present the audio archive at a conference in Spain. She was determined to use the time to document the experience of gay and lesbian Africans in Europe. She envisioned a grand tour of the continent. But after a bit of research, she noticed two trends: many of the stories were located in the United Kingdom, and many of these stories were those of asylum seekers.

This is how Thiam met Bisi Alimi, the asylum seeker from Nigeria.

While his story of coming out on national television in Nigeria had made Alimi famous, many admired him most for taking control of his own narrative and creating a public dialogue. Since being granted asylum in the United Kingdom, Alimi has continued to give regular interviews with the media and continued to work to raise the profile of issues facing the gay community in both Africa and the United Kingdom. After a mutual friend connected Thiam and Alimi, he agreed to participate in the Seeking Asylum video series.

Alimi envisioned another straightforward interview. He would recount his coming-out experience, perhaps answer a few questions on his asylum case. He wasn’t nervous. But Thiam pushed him to go to places he hadn’t been in a long time. “I’m very used to the camera,” Alimi says. “But when the questions started coming in, I got to the point that I had to remember so many things that I had to lock away in my past because they were too painful. And I broke down.”

Thiam stopped the camera and together they cried.

They eventually finished the interview. The documentary was well received: it became one of the flagship profiles for None on Record, it was a finalist in the PBS film festival and it aired on AfroPop. For Alimi, the experience was transformative. “That was the first time I had ever done anything like that since I came out. So it was pretty hard for me. But it was also very liberating. I felt like my story mattered.”

Because Alimi came out on national television, proving his sexuality to the British immigration system was relatively easy. But for most asylum seekers, cases are harder to prove. Many live deeply closeted lives in their home countries in an attempt to stem the homophobia that threatens them. A report released in October 2012 by the United Nations High Committee on Refugees found that gay and lesbian asylum seekers are more likely to face sexual and gender-related violence during detention than other asylum seekers.

None on Record provides a vehicle to share these narratives. It places gay asylum-seeking on the agenda while simultaneously providing a voice and a platform for those with lived experiences. This is Thiam’s ultimate goal for None on Record: to make people feel like their stories matter.

“There have been some hard, terrible stories. But there have also been stories of triumph. People changing their families’ minds, people finding their space in the world. People finding a way to live their lives as they choose. So it’s one of those projects that helps me to understand the complexity of the human experience.”

For more information about None on Record, visit noneonrecord.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra