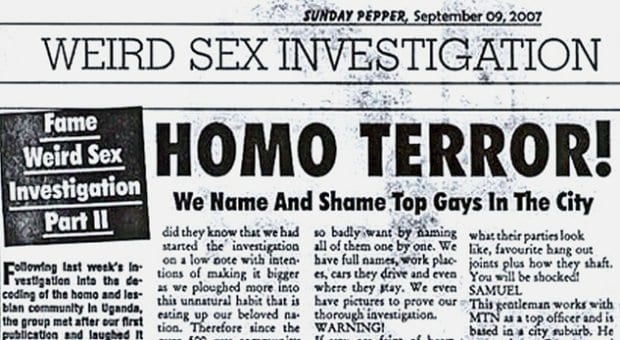

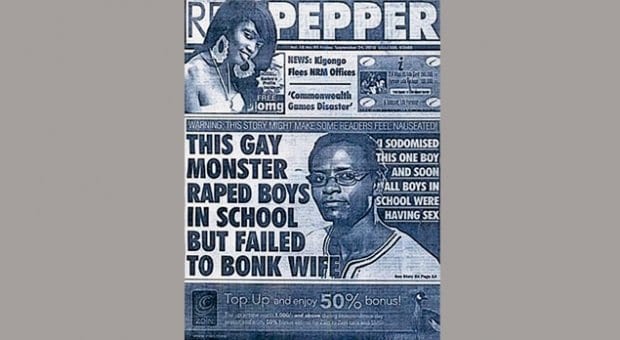

A typical newspaper headline in Ghana.

Former governor general Michaëlle Jean visits a JHR project in Ghana.

JHR trainer Robin McGeough presents a workshop at the African University College of Communications in Accra.

Ghanaian media has a long way to go on gay rights.

In a place as enormous and diverse as sub-Saharan Africa, it’s difficult to make any general claims about the status of gay rights. But despite the hard work of local activists across the continent, homosexuality remains a largely uncomfortable topic of discussion in even the most stable African democracies — particularly in the media.

“It’s as though gay rights are the last taboo,” says Rachel Pulfer, executive director of Journalists for Human Rights, or JHR for short. “It is a very touchy subject matter.”

Toronto-based JHR works on a wide range of issues, but primarily it has provided mentorship and resources for already existing media outlets in several African countries for more than 10 years. North American trainers exchange skills with African journalists and together produce stories about the human rights issues relevant to the local context, from witchcraft allegations in Ghana to female genital mutilation in Sierra Leone.

However, two former JHR trainers received international attention in March 2012 when they publicly grilled Nobel Peace Prize recipient and Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf about the possibility of decriminalizing homosexuality. “Voluntary sodomy” continues to be illegal in Liberia and punishable with up to one year in prison, but Sirleaf insisted she would veto any legislation that discussed homosexuality. Former British prime minister Tony Blair sat quietly beside Sirleaf during the interview.

Bonnie Allen, who was one of the reporters pressing both leaders on their positions on the issue, realizes that even asking this question was bold given the context. “One of the tricky parts of reporting on LGBT issues in Liberia is that it can actually raise the issue and create a backlash that might not have existed otherwise,” Allen says, explaining that homophobic violence increased in Liberia after Hillary Clinton declared to the United Nations that “gay rights are human rights.”

“One gay Liberian man told me he wished the media would leave it alone so he could live quietly in peace,” Allen says.

Indeed, tackling gay rights head-on is not always a sensible tactic for JHR trainers.

“In Uganda, for instance, I don’t know if it would be advisable to go after legislation of that kind with prominent politicians in that way,” Pulfer says, giving consideration to the seemingly unending threat of the notorious “kill the gays” legislation there. “It would be dangerous.”

Pulfer and other JHR trainers seem to agree that working with media organizations to ground their reporting in a broader human rights mandate creates the kind of environment where African journalists can tackle gay rights more explicitly. Allen remembers doing a workshop with students about the universality of human rights, including gay rights. Despite a little discomfort, the conversation was successful because it was among Liberians. “It was so much more effective than me standing in front of a classroom and preaching, because they can dismiss everything I say simply because I’m a ‘white woman from Canada’ and ‘it’s different there,’” Allen says.

The tension between a universal understanding of human rights and a necessary respect for culturally specific values seems to underlie the difficulty surrounding this conversation. JHR is constantly negotiating that line. “Be respectful of local norms up to a point,” Pulfer says. “But if a story is being covered in such a way that gay rights, or any human rights, are being abrogated, then it is the responsibility of the trainer to hold the line on that and to say, ‘We should cover this in a way that respects the rights of those involved.’”

Allen says that appealing to journalistic standards, such as those outlined in the Africa-wide Windhoek Declaration in 1992, is often also an effective way to align gay rights with human rights. “One argument that works well in Liberia is freedom of expression, because Liberians take that very seriously,” she says.

Robin McGeough, a JHR trainer who worked in Tamale, Ghana, also found that gay rights were best discussed in the context of a broader journalistic ethic. “The first time I brought it up, we were talking about bias and how to avoid it. I just put the topic on the table and let the students pick it apart,” McGeough says. “It was really well received.”

McGeough later designed a workshop on bias and presentations of queer issues in the media for other JHR trainers to use. In the workshop, racist North American headlines from the 1950s and 1960s are compared to homophobic headlines from today. Despite his willingness to introduce questions about gay rights in his work, McGeough, like many trainers, made the personal decision not to disclose his own homosexuality. “I didn’t want my personal life to affect the work I could do with the project,” he says.

Danny Glenwright, Xtra’s managing editor, was a JHR trainer in Namibia and Sierra Leone from 2006 to 2008. He made the same decision to play straight. “I didn’t push it at all; I went back into the closet,” he says. “I didn’t incorporate too much about LGBT issues into my training, and when I did, the reception was not very good. It was always laughed at. I left that to the other trainers who weren’t gay, as they weren’t putting themselves at risk by pushing it.”

Gay visibility in the African media can be dangerous for anybody, gay or straight. Defending gay rights automatically subjects the speaker to scrutiny.

Ato Kwamena Dadzie, a Ghanaian radio journalist who now lives in Canada, was the country director for JHR in Ghana from 2005 until 2008. After some hesitation, he became one of few straight voices standing up for gay people in the media. “I had to speak out very forcefully. I got a lot of very negative reactions to it, but I was fortunate that it created debates and got new perspectives on these issues,” he says.

However, despite dialogue on the radio and a relatively lively gay culture in Ghana, Kwamena Dadzie says that fear of being exposed prevents the conversation from opening up through other media platforms. “No gay person wants to come on television to defend gay rights; it would be a very stupid thing to do,” he says. “It’s a safety issue. It’s about employment, about social standing and acceptance. But at least on radio and in the newsroom, it’s now a safe issue to deal with.”

Of course, in relatively peaceful democracies such as Ghana or Namibia, local journalists and activists have more room to work on these issues than in countries like Sierra Leone or the Democratic Republic of Congo, where basic training and resources are far more crucial than social issues.

“As a gay person who lived in Sierra Leone, I can say there are so many other things to worry about,” Glenwright says.

Part of JHR’s mission, therefore, has to be adapting the kind of support it can build to each specific community. Unlike many non-profits, missionary projects or “voluntourism” companies, JHR seeks to build the capacity for long-term structural changes in each community through extended collaboration with local organizations. For this reason, JHR stays in a community for about five years, and trainers work for a six- or eight-month minimum. This kind of extended and specific project means accommodating different cultures and paces of progress.

“It’s a collaborative effort, and I think that grants an element of sustainability,” Kwamena Dadzie says. “JHR is very nimble. They are a force for change. Sometimes those changes come in leaps and bounds, and sometimes they come in tiny crawls, but you just need to be patient.”

For more information on Journalists for Human Rights, go to jhr.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra