Gay Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang is acknowledged as a contemporary master; Cinematheque’s retrospective, After The Deluge, provides an excellent chance to see what all the fuss is about.

Tsai is often compared to the late Rainer Werner Fassbinder – both directors are gay, both come to cinema from a theatre background, both employ a static cast of actors from one project to the next.

We might go further and note the audacious, overwrought style that both employ, though the parallels end here: Where Fassbinder’s work consistently threatens to fly apart at the seams in its chaotic, sometimes manic effusiveness, Tsai’s work often seems ready to collapse under the heavy weight of its contemplation; further, where Fassbinder’s work is often malicious and cynical, Tsai’s is terribly sad.

Tsai’s themes – of urban malaise, isolation and urgent sexuality – and formal style -meticulous framing, almost unbearable long takes and minimal dialogue – are the hallmark of all his films. Rebels Of The Neon God (1pm on Sun, Nov 4), his first feature, establishes this aesthetic in portraying two aimless Taipei youths and their wanderings through the decaying urban landscape.

Vive l’Amour (8:45pm, Tue, Nov 6) continues the project; here, a real estate agent uses a condo she is trying to sell for erotic encounters with a young hunk. Meanwhile, a second man, who’s gay, also uses the condo, sneaking in to lie beside the agent’s sleeping paramour.

The River (6:30pm, Thu, Nov 9) is perhaps the director’s most troubling work, dealing as it does with the appalling isolation and lack of communication that define the lives of a family: the mother, who seeks out sexual satisfaction with a porn merchant; the father, who frequents gay saunas; and their son, whose mysterious and painful neck injury drives him almost to distraction.

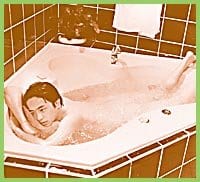

Frequent, concentrated moments of nothingness give way to minute, sharply meaningful but finally mundane action, as when the father, after lying asleep on a cot in a bathhouse, has an erotic encounter with another man.

Meanwhile, in the household itself, unanswered questions are barked into unrevealed rooms and mysterious water leaks are investigated. When, finally, there is communion between family members, the manner of that connection, and the punishment that it brings on, are shocking in the extreme.

One runs the danger of appearing overly reductive by referring to Tsai’s work as gay cinema, but there is no doubt that there is a gay sensibility at work here. His depiction of cruising, among men and women, on the streets of Taipei and in its saunas, captures perfectly the hyper-awareness of the sex-object that defines that experience; his camera peeks slyly and lovingly at the sculpted body of his star, Lee Kang-sheng.

But these are overt, sexual elements; one senses that something queer informs the very spirit of Tsai’s film world.

Clues to this sensibility can be unearthed in Tsai’s 1995 documentary effort, My New Friends (4pm, Sat, Nov 10; screened with Tsai’s early feature, Boys), in which the director interviews two HIV-positive Taiwanese men. The conversations are frank and friendly and cover some familiar territory: sexual awakening, coming out, HIV infection and its attendant rage.

But the most striking element of this film is, in fact, a lack: At their request, the interviewees are only shot from the neck down; their faces are never seen.

This formal measure underscores the repression withstood by gay men in Taiwan, and, more broadly, Chinese culture. And it is this repression, presumably experienced by the Malaysia-born director himself, that we might well imagine leads to the brooding disconnection that characterizes Tsai’s fiction films and the lives of the characters within them.

This is distressing, powerful cinema – not to be missed.

All screenings take place at the AGO’s Jackman Hall (317 Dundas St W); tix cost $8. For other Tsai films, call (416) 968-FILM.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra