As the 1970s progressed, open protests, marches, rallies and demonstrations became less frequent as love beads, tie-dye shirts and bell-bottoms were exchanged in favour of neckties, wide lapel sport jackets and Fortrel pants.

Ending discrimination based on sexual orientation and entrenching equal rights for gays was now a fight on two fronts: from the inside as well as from the outside.

Activists continued to dog political candidates and press them on gay rights issues. For example, during the 1972 BC provincial elections, gay activists in the Vancouver-Burrard riding pressed the Social Credit incumbent on whether he would help gays achieve equal rights. He responded that he would help gays “as much as I can,” but then added a cautionary note. He said that those belonging to gay liberation organizations were in a dangerous situation if they continued being vocal since “one day society will want to castrate the lot of you to stop you reproducing your kind.”

He received less than 13 percent of the popular vote. However, it is not only the defeat of an incumbent who clearly didn’t support gay rights-or, apparently even understand the meaning of homosexuality-that makes this particular election significant.

When elected in the Vancouver-Burrard riding in 1972, Rosemary Brown became the first black woman elected to a Canadian legislature. She is believed to be the first politician in Canada to make unsolicited public statements recognizing gays as an oppressed minority seeking equal human rights, and she introduced legislation in BC to end discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

While Brown was the first, she wasn’t the last.

Throughout the ’70s, gays and those supporting gay rights were elected to office in all levels of government in Canada (for example, a closeted Svend Robinson in 1979). By the end of the decade, organized mainstream political manoeuvring replaced the grass-roots, street-level political activism that had permeated the gay community. Our collective vote became our collective voice.

The nature of Pride celebrations reflected this shift. In the early ’70s, Pride celebrations were overtly political in nature-they were more marches than parades. It wasn’t until 1978 that Vancouver’s Pride Parade was more a celebration of our community and its achievements than it was a march meant to achieve a political end.

So, it is just as much a mistake to mark 1978 as the first year of Pride celebrations as it is to mark Stonewall as the beginning of the gay rights movement. However, it does mark the year of Pride as we now know it.

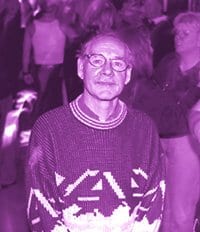

I wanted to find out more about how this first celebration came about, so I went to the source and met with two of the founders of Vancouver’s Pride Parade: Terry Wallace and Gary Penny.

They were already deep in conversation when I arrived, and as I approached their table, my first impression was that their interactions had an air of casual, relaxed familiarity that friends develop only with time-a long time. The low-key conversation continued for a bit after I joined, and then I asked the first of my questions about the beginnings of the Pride Parade. The relaxed banter instantly transformed to a conversation suddenly animated and charged with a fiery passion.

They talked of the importance of Pride-the importance of community. They related stories of systemic discrimination based on sexual orientation and they talked of friends being beaten simply because they were gay and then having authorities blame the victim for the crime. They talked of the hurdles in establishing safe, comfortable social gathering spaces for the gay community. Both Penny and Wallace believe that it is only by coming together as a community that we will ultimately conquer discrimination, hate and move toward true equality.

“Diversity is our greatest strength and our greatest weakness,” says Penny, “and Pride is the one day of the year we come together as a collective.” The idea that as individuals we are empowered by community, and that we, in turn, strengthen community, gets no argument from me.

“Pride has grown beyond our wildest dreams,” says Wallace. “In fact, the first one was more a walk down the street than it was a parade.” Both Wallace and Penny agree that even with all that has been accomplished, the underlying need for that first celebration is unchanged even today.

“We still have a long, long way to go,” says Penny. They refer to the old adage that you can’t legislate attitude and that outside the comfortable confines of the West End, there are lots of people who still hate, still discriminate and would take away any gains we have made towards equality if given the chance.

As I watch and listen, I think of MP Elsie Wayne’s comments and the caution provided by the Social Credit candidate in 1972. Different time, different people, and different words: same message. They want us back in the closet. They want us to go away.

People like Penny and Wallace know what it is like to live without rights and they have worked too hard to bring us all to where we are today. Speaking with them reinforces for me that each of us needs Pride. We need to put aside our differences for that one day and celebrate our individual and collective achievements.

We need to celebrate who we are, and to celebrate proudly.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra